Search results

A Life’s Work Back to top

John Soane was certain that his work as an architect would be of interest to future historians. We see this in the care he took of his drawings, which has permitted critics and historians to carefully follow the path of his career. Proof of the esteem he held for his work is also apparent in his collaboration with the architect and renowned draughtsman Joseph Michael Gandy, whose remarkable renderings of Soane’s work are just as impressive today whether they depict perfectly realised designs or visions of them as ruins. Gandy’s illustrations of the Bank of England are a perfect example. Soane was aware of how the essence of architecture was manifest equally in its process of construction as it was in the vision of its ruin. The extraordinary panorama of all his work makes manifest how Soane foresaw his work becoming history.

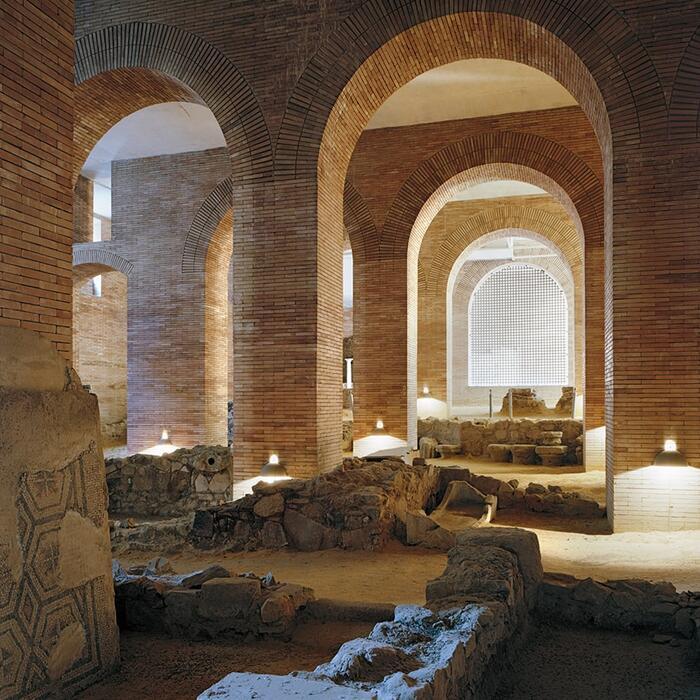

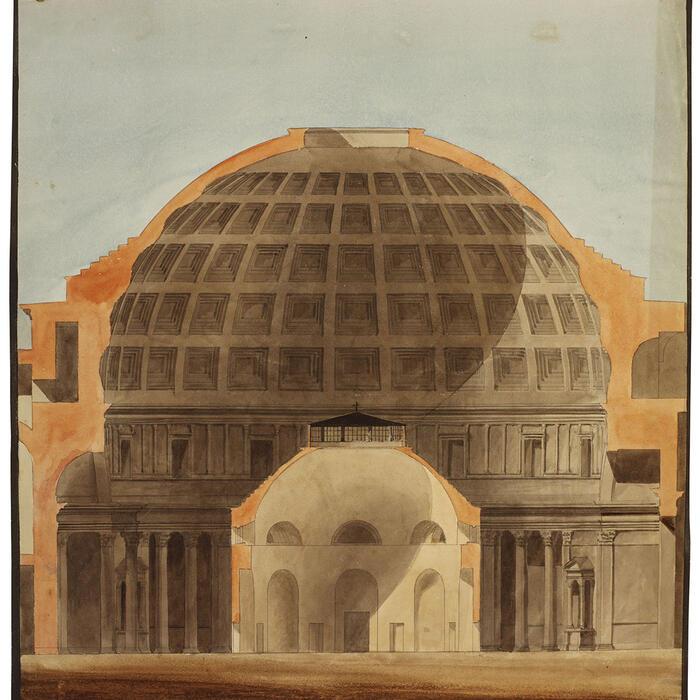

Soane seemed destined to be an architect from birth, and fatefully his tutelage began under George Dance the Younger. It would be difficult for him to have found a better master and guide. Dance, who had spent six years in Rome and had acquired from his father a solid professional training, quickly recognised Soane’s talent and encouraged him to enter the Academy and later to move to Rome. For Soane, I feel both proximity and a profound sympathy for different reasons. Like him, I also had the good fortune to begin in architecture under the guidance architects I consider my masters, Saénz de Oíza and Jørn Utzon. Like him, I spent two years in Rome at the Academy, later a constant influence in my professional life. In fact, on three occasions – in Mérida, Tarragona and Cartagena – I have had the luck of finding myself very literally in the midst of Roman architecture.

And without reaching the extremes shown by Soane, I can say that I have devoted my life to architecture. In my work, Soane has figured strongly on several occasions. First, for the skylights in the Thyssen Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, then later in the museums at Stockholm and Houston, Soane’s Dulwich Picture Gallery was a clear inspiration. The vaults of the Atocha Station and the light wells at the Don Benito library also recall motifs frequently found in Soane’s work – recognising implicitly that in architecture there is no need to fear precedents.

In Search of Histories Back to top

The awareness of the intimate connection between time and architecture that we find so strongly present in the figure and work of Soane shows us how knowledge in architecture has moved from the treatises of the past to the histories we now rely upon. The critics and historians writing these narratives have always made use of the modern movement as a fundamental point of reference in their accounts. Today, this reference to the modern movement is no longer pertinent, and I would like to take the opportunity to consider a new historical paradigm that could describe the principles and criteria prevalent today.

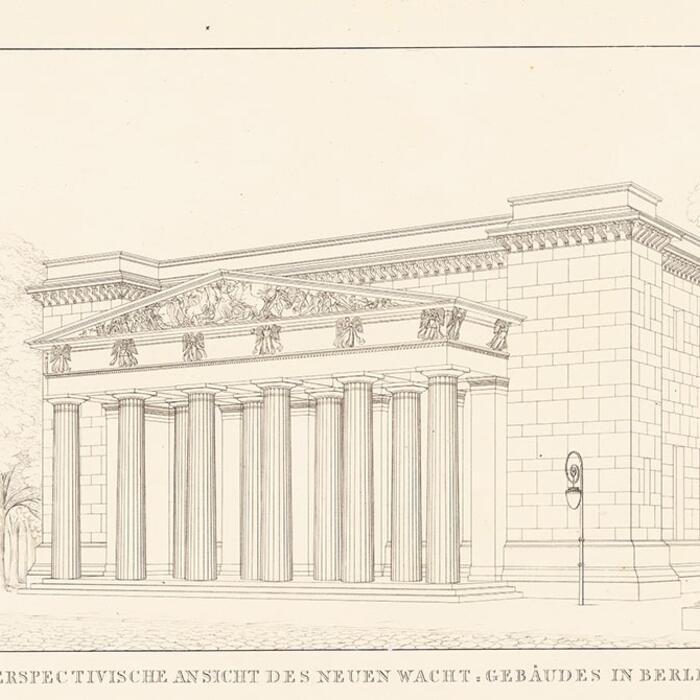

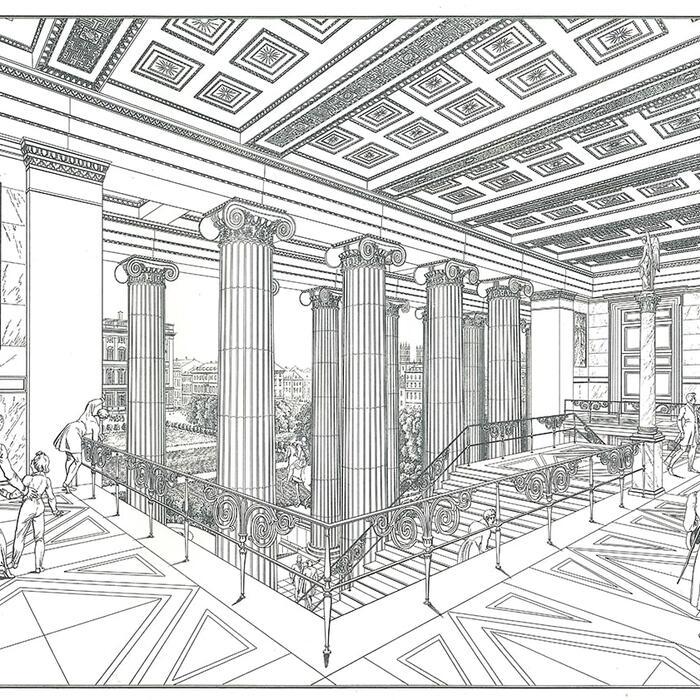

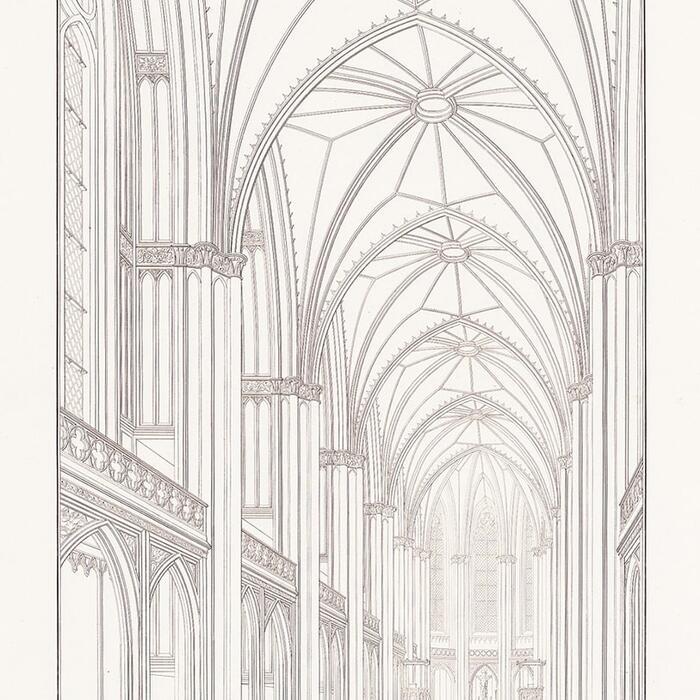

During Soane’s lifetime, Napoleon had shown that it was possible to inscribe oneself in the destiny of nations. His contemporary, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who witnessed his campaigns, explained history in similar terms. This sudden consciousness of history, which occurred at the beginning of the nineteenth century, would be present in many aspects of daily life and would soon manifest itself in architecture. As a result, we see history come to the fore in architecture, as architects made liberal use of historic styles. History – and the knowledge of histories – provided architecture with useful ingredients, endowing it with a disciplinary status similar to that of physics, chemistry or the natural sciences, and taking it beyond the strictly artistic order to which it had been confined. The work of an architect such as Karl Friedrich Schinkel reveals an architecture founded on historic styles according to each occasion.

For Schinkel, historical references provided options that permitted him to associate programme and style, with an understanding that style was simply the architectural material at his disposition. The Doric was used for the most respected institutions, the Gothic for a church, or the vernacular for a prince’s summer palace. London has been witness to historicist buildings, such as the Houses of Parliament. This interest in historical precedents in architecture is sustained throughout the nineteenth century. Architects are converted into historians and travel in search of documentation of obscure buildings that often reappear in contemporary works.

This willingness to use history as a quarry of material establishes an architecture capable of reflecting the spirit of the new emerging nations that arise during the course of the nineteenth century. It is through history and its use that we can understand the creation of so many national styles, a phenomenon that continues well into the twentieth century.

A New Architecture Back to top

By the end of the nineteenth century one could detect a certain resistance to the academic tradition, present in both art nouveau and in the call to abandon ornament and the appeal of elemental volumes evident in the work of an architect such as Adolf Loos. But it wasn’t until after the First World War that a new order was established. In the late 1920s a new architecture appeared that sought to reflect the spirit of the time so clearly present in the ocean liners, trains, automobiles and fashion. The urgency to give form to built work coherent with the Zeitgeist appeared simultaneously in different countries as expressed in numerous manifestos. Naturally, these changes did not come easily. A clear example appears in a city like Hamburg, with the reconstruction of the city centre and a building like the Chilehaus where the architect Fritz Höger celebrates its strong expressionist character. Just a few years later, in 1927, the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart appeared as a tour de force of the new architecture announcing the birth of the modern movement.

History and manifestos, then, instead of treatises. Action, construction – instead of the elaborate doctrine or theory that comes from the analysis of built precedents. But it would be Sigfried Giedion who would convert the narrative of the new architecture into doctrine. Giedion aspired to establish the modern movement as a fully consecrated style and its own historical category through which the new architecture could be explained.

It is Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture that should be considered the first of these narratives to do so. Presented as an alternative to the treatises, it makes the modern movement the inevitable reference in charting the evolution of architecture. And it is clear that this interest in history has become manifest in many different formats ranging from monographs on architects to critical essays relating architecture with other disciplines.

Myth of the Modern Back to top

We recognise that we live in a new age, that the twenty-first century’s digitalisation represents a transcendental change – like mechanisation was for the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – but it is difficult to clearly define the formal character of this new culture. Contemporary architectural expression, in spite of its global presence, isn’t unified and inclusive in the way it was with the first generation of modern architects, trying to give form to the ‘First Machine Age’.

In spite of situating ourselves through histories that take the modern movement as their cornerstone, today’s architecture can hardly be explained with this reference. I believe today we have moved so far away from the modern movement that we ought to establish a new paradigm. In other words, I believe we no longer need the modern movement to explain and interpret architecture today, because, as Colquhoun writes, the modern movement is only a myth and ‘the myth itself has now become history and demands critical interpretation’. And while some bold architects maintain the inertia of the heroic role assumed in the past, it is difficult to believe that they have the power of discerning the spirit of the age and its symbolic forms. In other words, the faith modern architects had in a shared doctrine is no longer possible.

It would be absolutely impossible today to make a list of architects who share common ground in the way the architects of the Weissenhof or the International Style exhibition had. Neither common formal features, nor common ethical and aesthetic criteria, allow us to imagine a collective of architects working with a shared language.

Today’s architecture reveals a diversity which eludes a common language or a single characteristic material such as the white stucco was for the modern movement. A not-so-distant effort to preserve this common language appeared with the New York Five architects who, as we know, failed in their experiment. Only an architect like Álvaro Siza continues to work with a well-established language that, in his case, is clearly his own personal version of modernism. Other architects, such as Herzog & de Meuron, emphasise this diversity, making the choice of material a key issue for understanding each specific building. The variety and contrast of materials that characterise their work is a clear token of their linguistic eclecticism.

Between Future and Past Back to top

Having touched briefly on some of the issues characterising today’s architecture and having accepted that today’s architects have been taught from histories, rather than manuals and treatises, I ought to insist that our contemporary architectural world cannot be understood as the coherent evolution of the modern movement. We therefore can no longer rely the principles that inspired it. It is a situation not very different to that of John Soane when, at the end of his life, from his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, he could see that the architectural canon and the language of classicism were no longer valid and that the new world of architecture was something he wouldn’t recognise.

If we no longer have a clear idea of the attributes that ought to belong to a building – something that indeed the architects possessed from the Renaissance to the Beaux-Arts, and even in the times of the modern movement – and instead can only understand buildings in a temporal sequence, then we should ask critics and historians to decipher the significance of today’s architecture – a new interpretation that establishes goals pursued in contemporary architecture.

It is essential to know something more about our present society in order to understand the needs and desires of our fluid, mercurial society. One of the greatest contrasts between our times and the period between the two Great Wars is that they had a sense that progress could be anticipated, and that the Zeitgeist could be made manifest. Architects in the 1920s and 1930s were able to think in utopian terms about the city because they felt themselves capable of giving shape to the spirit of the times. That is something that we don’t dare to do today, when only the most radical pragmatism seems to prevail.

I would like to know a bit more about this ineluctable, immediate future that seems destined to appear without our intervention, without room to believe – as the architects of the Modern Movement thought – that we are contributing to the development of the ‘Idea’ that Hegel thought sustained history. For this reason, I eagerly await an explanation of today’s architectural world without a reference to the past, given that it seems so little related with our present. I think this presents a great challenge to those who seek to account for today’s architecture. I wonder whether we should still consider architecture only as the work of individuals, and cities as the outcome of the almost uncontrollable process, or if there is still a possibility of saving the legacy of our cities. And if taking cities as frames of reference, we are able to keep their integrity when they allow our eagerness for novelty to develop, which is implicit in human life and highly stimulated by the advance of science. I would very much like it to be possible and I would like to see architecture, the discipline to which Sir John Soane dedicated himself in body and soul, serving as the instrument to make this very much needed mediation between future and past. Surely architects will welcome critics willing to become historians in order to explain how the formal world has come to be what it is today. This is a formidable challenge for those who would interpret it – but one that is necessary.

Header image credit: Photo Michael Moran, courtesy Rafael Moneo Arquitecto

Website Accessibility statement Back to top

To find out more about Website Accessibility on our Website Accessibility Statement page.

Learning from Johannesburg Back to top

I have never thought of myself as a photographer, only an architect and urbanist, but for seven decades I have taken photographs and used photography to illustrate the ideas behind what I teach, design and write. These reflect so much of who I am.

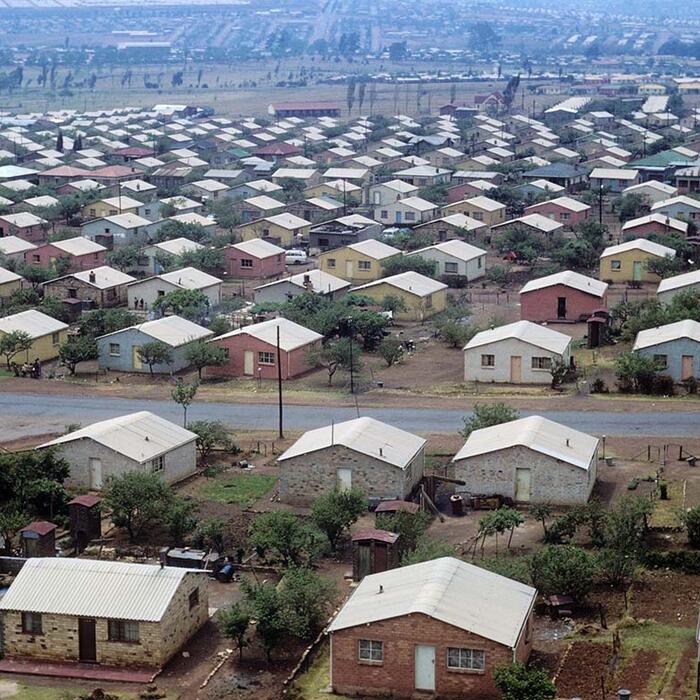

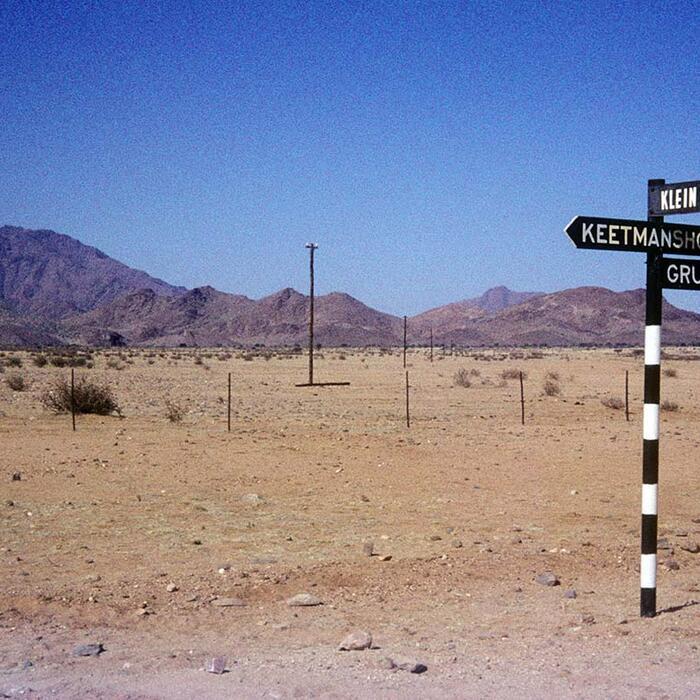

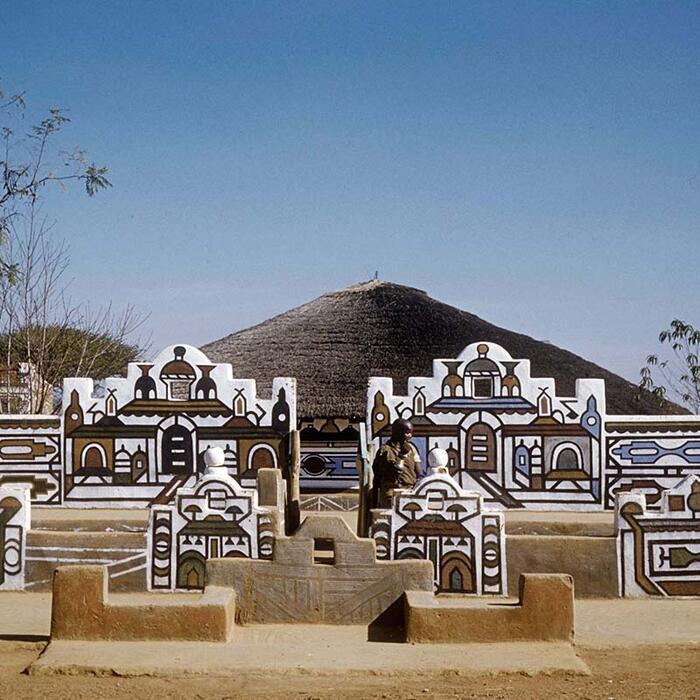

I was born in 1931, in ’Nkana in Zambia. In 1933 my parents moved back to Johannesburg which was then less than 50 years old and very much a mining city, and if it had gateways at all these would be its cooling towers and mine dumps. In South Africa I also learned to love so much of its own architecture, like Kwa Zulu huts, made of straw and mud; and the village houses of the Mapoch Ndebele, whose wattle-and-daub structures fused Arab influences from the north, Mapoch traditions of hand-painting patterns from their beadwork on their houses, and a new idea of decorating their entryways with depictions of the fronts of nearby suburban houses. At the same time I was very attracted to the Cape Dutch rural vernacular, like those in the town square in Stellenbosch, and the gabled farmhouse buildings nearby, whose builders are identified by the particularities of their pediments.

Learning from London Back to top

In 1952, I recognised I needed further training and moved to London where I found work with the architect and planner Frederick Gibberd. At the same time I visited the Architectural Association and met people I liked, who encouraged me to apply. As a student there I encountered John Soane, via John Summerson, who was then director of the Soane Museum and an AA lecturer. He taught a course on classicism, with a special focus on Italian and English mannerism and architects like Jones, Wren, Nash, Hawksmoor and Soane himself. Through Summerson I considered ranges of building types and studied buildings within the wider tissue of the town. By combining insights from architectural history, social thought and urbanism, he helped me prepare to be both an architect and a planner. I’ve since used Georgian architecture and Summerson’s slice of the world as a framework to study everything from Soweto, Levittown and American inner-city housing, to Lilong, academic complexes and The Strip. And eventually his interpretations also guided us in designing the National Gallery Sainsbury Wing.

Another touchstone at the time was a reprint of a 1929 lecture by Le Corbusier called ‘If I Had to Teach You Architecture’. In it he encourages students to look at the way a boat docks at a harbour or at the layout of a train kitchen – ie, lovable reflections of 1920s functionalism. If only life were that simple! In the same text Corbu offered another instruction to go behind a building, to where architects consider practicalities rather than aesthetics, and where you can find interesting things. Dutifully, I photographed the backs of buildings on Bond Street and there it all was. The lack of pretension of behind-the-scenes London also seemed to fit with the ideas of Alison and Peter Smithson and the Independent Group, and their version of mannerism as it gravitated around pop art and brutalism.

Learning from Italy Back to top

In July 1956, with my first husband Robert Scott Brown, I packed up and left the Elysian Fields of Georgian London and spent six months in Italy. We set off in our three-wheeled Morgan, accompanied by a bag of spare parts from the Morgan factory. Our destination was a CIAM summer school in Venice and our route was devised by Robin Middleton to cover a maximum of mannerist art and architecture.

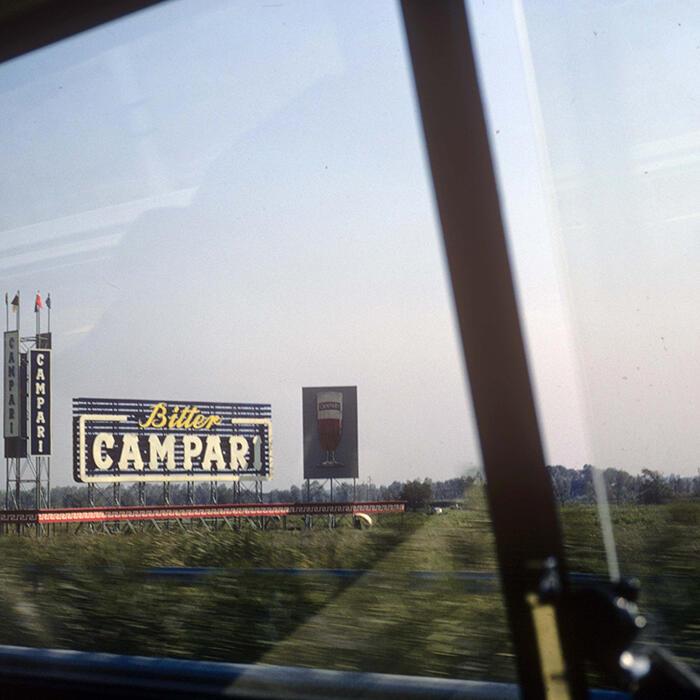

In Venice I added further examples to the architecture I loved in South Africa and London: grand palazzos whose frontages followed the age-long design code Summerson had described, but with variations in window arches and widths that indicated Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque eras. When autumn came we drove south, sightseeing in Florence and Sienna and wintering in Rome, photographing roadside signs and symbols on the way, and where we worked for six weeks for Giuseppe Vaccaro. In the New Year we went to Naples, and continued to photograph interesting urban forms.

The linear city was an object of fascination at the time, and was seen to be a logical response to railways and their stops and a means of assuring urban and rural access in cities. Earlier the previous summer, the theme of the CIAM school was planning a future Lagoon City on Mestre, an industrial town on the Venetian mainland, which we took as a chance to design a linear city of our own. Though rejecting rigid CIAM urbanism we proceeded with a Sienna linearity that was not absolute but responded to topography and to where you could walk or grow vegetables. And the donkey? Well, it was the train and in our new era it could go at 100mph! ‘But how would it stop?’ our jury asked. Unbelievably, we announced, ‘That doesn’t matter.’

Learning from Philadelphia Back to top

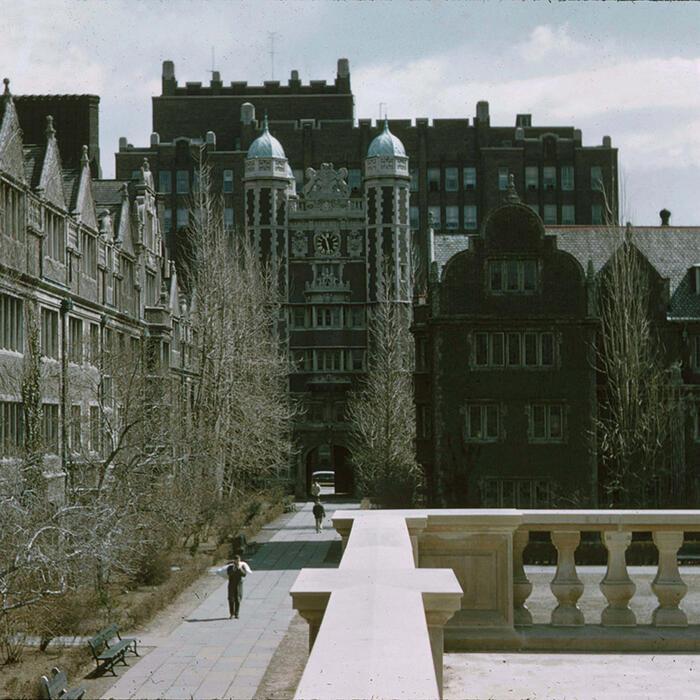

When we were finishing at the AA, Peter Smithson had asked what Robert and I would do next, and when we told him we wanted to study city planning in America he insisted we go to the University of Pennsylvania, to Louis Kahn, who he had been corresponding with for several years. We took his advice and after Italy enrolled as planning students. We soon discovered that Kahn ran design studios open to architects in architecture not in planning: ‘Sociologists believe in 2.5 people’, he argued, ‘how can you believe in them?’ We tried to switch, but then discovered that we actually liked the planners – among them a new generation of social scientists who were advance guards of the New Left, and who endorsed ‘advocacy planning’, where you find out what the people you are designing for really want, rather than imposing architects’ oughts on them.

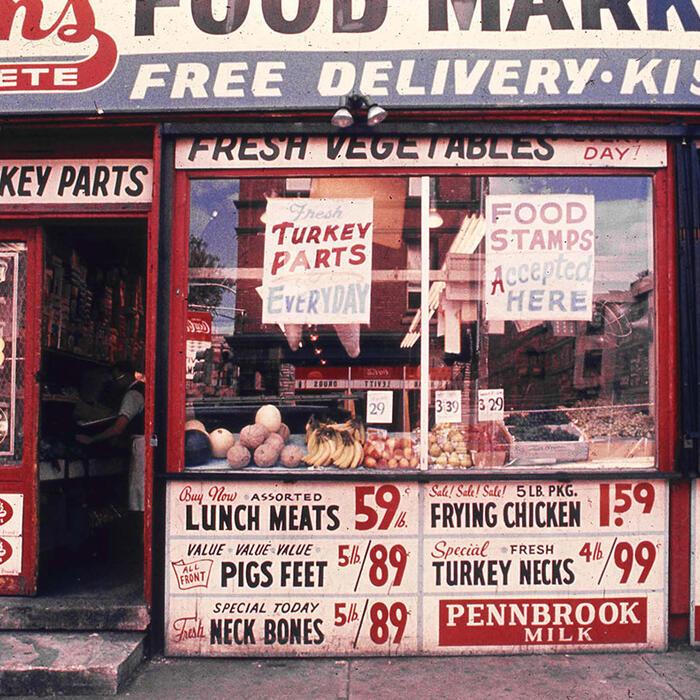

A short while later, in 1959, Robert was killed in a car accident. I went home, but my family and teachers at Penn all said ‘finish what you so loved doing'’ Sorrowing deeply, I continued my studies, and soon found richness beyond architecture in land economics, regional science and the systems planning that went with them. And as my interests widened, I found more reason than ever to photograph, not least because I was doing so to teach. I was also drawn to Philadelphia street life, its colours and architecture, and the dangers of crossing the road. At the same time, I explored the housing stock in neighbourhoods rich and poor. Philadelphia colonial townhouses were Georgian but built of bricks more finely wrought than the London yellow stocks – though I love these just the same.

I met Bob Venturi at a faculty meeting at Penn. Architectural preservation brought us together. At one of our weekly meetings the scheduled demolition of the former university library building was on the agenda. I was shocked to discover that most of my colleagues wanted it torn down. I offered a case for the defence, and this argument prevailed. After that the young architect who had heard our New City presentation with Kahn came up and said, ‘My name’s Robert Venturi. I agree with everything you said.’ I think I shouted at him, ‘Then why didn’t you say anything!’ In 1968 Bob and I moved from the second floor of the Vanna Venturi House, into a 24th-floor apartment in the Society Hill Towers designed by I M Pei. From this domestic version of an airplane window I could observe all of colonial Philadelphia below, as well as spot planes landing at the airport, watch over whole districts and weather systems and see individual snowflakes driving towards me. Armed with these aerial views, in my first-year teaching studio I set projects that sent students into Philadelphia. Architects often talk about designing public space but I wanted them to learn, before designing, how people actually use such spaces, and to listen when social planners warn that it isn’t public unless the public uses it.