Search results

Stan Allen Back to top

Learning from Moneo

In 1984, nine years after the death of Franco, as the Spanish cultural scene was sparking into life, I was fortunate to spend a year in Madrid working for Rafael Moneo. I learned many things from Moneo, not the least of which was never to imitate his formal choices. Moneo insists on taking every project on its own terms, and rarely repeats; he is a relentless critic of his own work, constantly editing and revising. He would never impose a ‘signature’ style on a building for the sake of consistency. I often tell my students that the iterative character of design requires that the architect embrace a paradoxical mindset, a thought which also has its origins in my experience with Moneo. In other words, to drive a design project forward, at any given moment you have to be entirely convinced that your solution is the right one. It takes time and effort to draw up a project, and you can’t do that without belief in the solution. But the moment you see its form, its intent and its contours, you have to be ready, without regret, to revise and rethink – up to and including starting over from scratch, something I saw Moneo do countless times.

As much as I learned from Moneo, I also learned from the other young architects in the office. I learned not to overwork a drawing – freshness and immediacy were the qualities sought after, which demanded concentration, efficiency and a sense of knowing when a drawing was complete. I gained a respect for the depth and richness of architectural history. I was introduced to architects such as Ignazio Gardella and Luigi Moretti, who had their own way of working with history. I learned about building and materials. There is a certain quality to the drawings produced in Moneo’s studio that always anticipates their realisation as construction: there are few blank surfaces; brick coursing is always hatched, concrete stippled, and each joint and material transition is notated. Paving is always indicated in plan drawings.

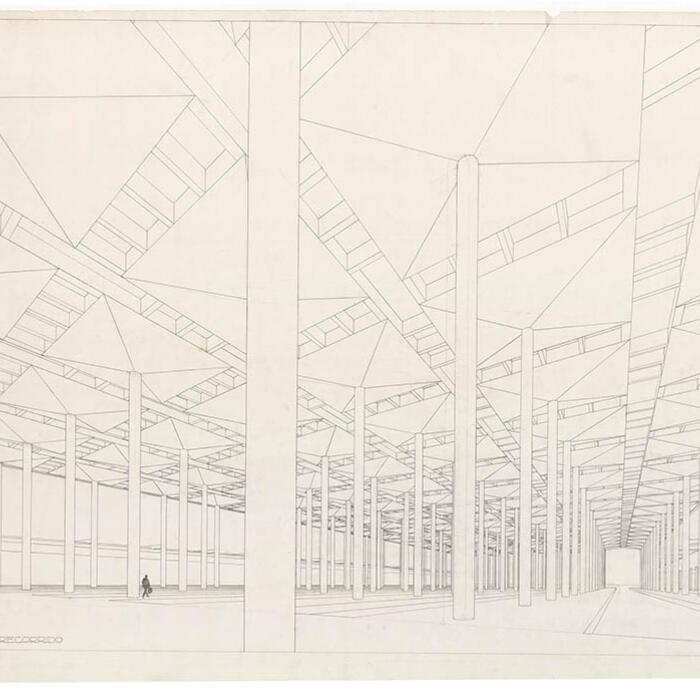

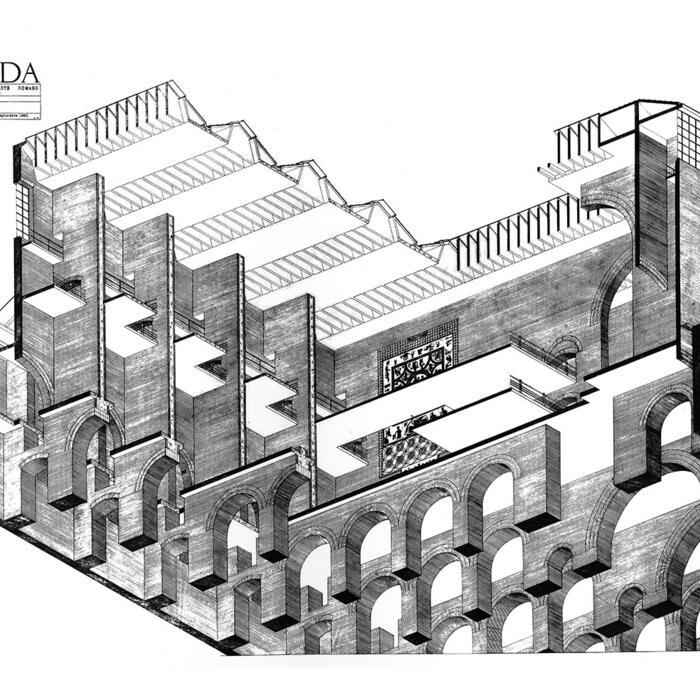

Intellectually Moneo is also, for me, a model of a thoughtful architect who uses writing to reflect on his practice, and is always generous (although rigorously critical) in assessing the work of his peers. My speculations around the idea of ‘field conditions’ can be traced back to the Mosque at Cordoba, which I first visited with Moneo on the way to a building site. The essay ‘Infrastructural Urbanism’, which argues for the agency of a hybrid architecture/engineering approach to urbanism and public space, owes a debt to the Atocha Station in Madrid, the first project I worked on in the office.

Another piece of advice I give to my students – particularly when they seemed to be bogged down with a project – is to ‘work less and produce more’. It’s not something Moneo ever said, but an idea absorbed in the atmosphere of his studio. What I mean by this is that you work best in short intense bursts of concentrated productivity. In his studio, Moneo would go from desk to desk, making corrections, and asking each one in turn, ‘but why isn’t it finished yet?’ (Often, it seemed, minutes after you had started a drawing.) Design is a process of accumulating information about a building that exists only in the imagination. In order to achieve the density of the real that Moneo looks for in his architecture, you have to build up many layers, and look at a project from all angles, understanding exactly what each drawing was intended to convey and communicating that information with a minimum of elaboration. Making architecture is a long and often difficult process; it requires patience but also passion and commitment. When you see Moneo at work, you understand that he loves architecture. It fascinates him endlessly and gives him pleasure. Sometimes we forget that this is what it is all about.

Stan Allen is an architect working in New York and Professor of Architecture at Princeton University. His most recent book is Situated Objects (2020, Park Books).

Mark Lee Back to top

Rafael Moneo at Harvard (from Tange to Gropius and Back Again)

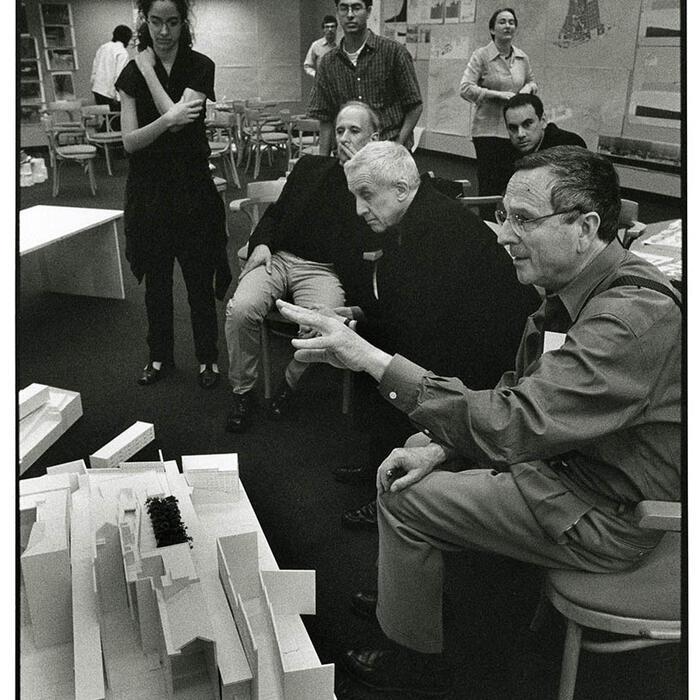

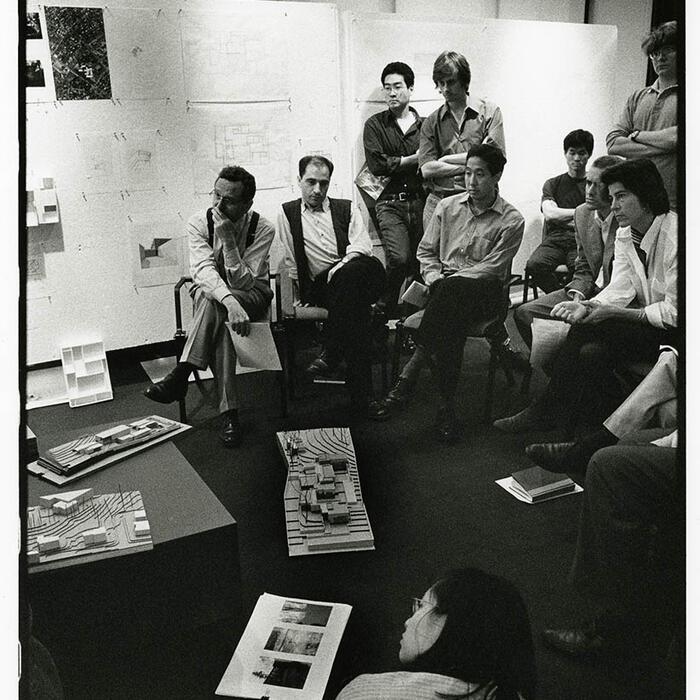

When Rafael Moneo was appointed as Chairman of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1985, he delivered the inaugural Kenzo Tange Lecture titled ‘The Solitude of Buildings’. Delivered at a time when American architectural education was entrenched in debates about theory versus concerns for practice, the Tange Lecture posited building construction as a foundation from which theoretical concepts could be generated. Already a significant practitioner and a respected figure in theoretical discourse, Moneo charted the course of his forthcoming chairmanship at Harvard in bridging the division between theory and practice.

Five years later, upon the completion of his term as Chairman in 1990, Moneo delivered the Walter Gropius lecture titled ‘Reflecting on Two Concert Halls: Gehry vs Venturi’. The lecture considered two American projects – one that was eventually built with significant alterations and the other never built – as lenses to view the global state of architecture. Observing the waning cultural importance of architecture in relation to ephemeral media, Moneo questioned the fundamental necessity of architecture and the subsequent role history plays in our society.

The two endowed lectures that marked the tenure of Moneo’s chairmanship at Harvard were, coincidentally, named after two architects who wrestled with the role of history in their respective pursuit of modern architecture. Separated in age by thirty years, Walter Gropius (1883) famously tried to abolish the history of architecture course at Harvard as a platform for a positivist project, while Kenzo Tange (1913) strove to integrate traditional typologies and motifs with modernism in his search for a national identity in postwar Japan.

These disparate positions occupied by Gropius and Tange encapsulate a significant tension between the burdens of history and the imperatives for progress that permeated Moneo’s teachings. The belief that architecture should always be situated between theory and practice, and its inevitability as a historical project is an important lesson I learned from Moneo as a student. It is a principle that I continue to espouse, and one I continue to model for aspiring architects.

Mark Lee is the Chairman of the Department of Architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design and a partner in the Los Angeles and Boston-based office Johnston Marklee.

Caring for Soane's collection Back to top

How do we preserve this wonderful building and collection? How do we keep it open to all, while protecting it from damage by bags, shoes, and elbows? Not to mention dirt, dust, light, and pests? Find out on this trail, as you experience the museum through the eyes of our conservators, curators and Visitor Assistants.

Peter Eisenman Back to top

Moment of Clarity

It is not very often that one witnesses, or even participates in, a life changing event. However, that happened to me while I was with my friend Rafael Moneo. It was in Venice, in the summer of 1985. I had just finished a three-year stint teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design at the invitation of Harry Cobb, then chairman of architecture. All three of us, Cobb, Moneo, and I, happened to be in Venice at the same time. Cobb, who was looking for his successor at Harvard, had provisionally offered the position to Moneo. Moneo found me and said we needed to talk. So we set off on a long, rambling, slow walk through Venice, with no particular destination in mind. As we walked and walked in the mid-afternoon heat, Moneo talked continuously. He talked about architecture, his work, his family, his life in Madrid, but he always returned to the subject of his future, which Cobb’s invitation had made so urgent. At a certain moment, Moneo abruptly stopped and turned to face me. Almost shaking, he asked, ‘What shall I do about Harvard?’ And then immediately he made a self-aware statement of enormous clarity: ‘Peter,’ he said, ‘I want to be a world architect not just an Iberian one!’

The rest, as they say, is history: the distinguished international career, as both practitioner and teacher, of a great world architect.

Peter Eisenman is principal of Eisenman Architects. His career has combined the work of practice and the completion of numerous projects with academic appointments, including Yale University, where he currently teaches, as well as Cambridge University, Harvard University, Princeton University, Ohio State University and the Cooper Union. In 2020 he was awarded the Gold Medal for Architecture by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Header image credit: Photo Michael Moran, courtesy Rafael Moneo Arquitecto

Shelley McNamara Back to top

A Way through the Fog

What does it feel like to be written about by Kenneth Frampton? This was one of the questions posed when we were invited to write this piece. Our first monograph was published by Gandon Editions in 1999. When we phoned Kenneth Frampton to ask if he would write a piece about our work he said, ‘send me some drawings!’

We did not know him well at the time. We were given a time to phone again and, full of apprehension, we were relieved to hear his response which was economical: ‘Beautiful work, I will write a short piece.’ His short essay was on the whole, extremely positive, but embedded in there was a sharp and deserved criticism of a project where we had clearly lost our way.

When writing about the Bocconi University project in Milan, he kept making sketches on the occasion of his visit to the building. The work was interrogated as were the architects. Flaws were spotted. When he asked, ‘Could you not have made a better handrail than this?’ you knew that he was measuring what he saw against all the handrails in all the world in all the great buildings he knew so intimately.

We were acutely aware, on the occasion of this site ‘inspection’, that we were in the hands of a practising architect – an intellectual who has designed and built buildings. He was questioning as an insider, someone who knows the score, the ‘plight’ of the architect in the struggle to make a building which is in the end a sum of imperfections.

Given this reality, what sustains the making of a building – what delivers it into the realm of architecture – is the vision, the strength of the idea, the passion and feeling invested by everyone involved.

Kenneth Frampton’s experience as a practising architect makes him, in our view, both more sympathetic and more critical, and therefore a positive response from him is all the more treasured.

His written piece on our building was indeed treasured by us. It was poetic, expansive, soaring through the heights of spatial language, historic reference, societal meaning.

For so many years, he has dissected great buildings and revealed their mysteries and qualities to us. Their origins, their place in the continuum of tradition, their tectonics within the vast language of construction. He reveals his own passion for craft, for integrity, for the haptic sensual component of a building. He is a custodian of the core values of architecture.

Kenneth Frampton tells you like it is. What is good and what is not. What is confused and what is clear. He has been our way finder in the fog of making work.

Shelley McNamara co-founded Grafton Architects with Yvonne Farrell in 1978. They are the 2020 Pritzker Prize Laureates.

Flaxman at the Soane Back to top

Sir John Soane and the sculptor John Flaxman were both professors at the Royal Academy – and friends. Eight years after Flaxman’s death in 1826, his sister-in-law Maria Denman began giving Soane his drawings, 75 of his models, and 70 other objects from Flaxman’s own collections. Today, they’re hidden away in nooks and crannies all over the museum. Use this trail to find them.

Flaxman at the Saone pdf

John Miller Back to top

Kenneth Frampton, Architect

Ken has been one of my closest friends since we both enrolled at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1950. After seventy years there is much to reflect upon, too much perhaps in a few lines.

His reputation as a writer on architecture is well known. What is perhaps less known, is that he was also, however briefly, a practising architect.

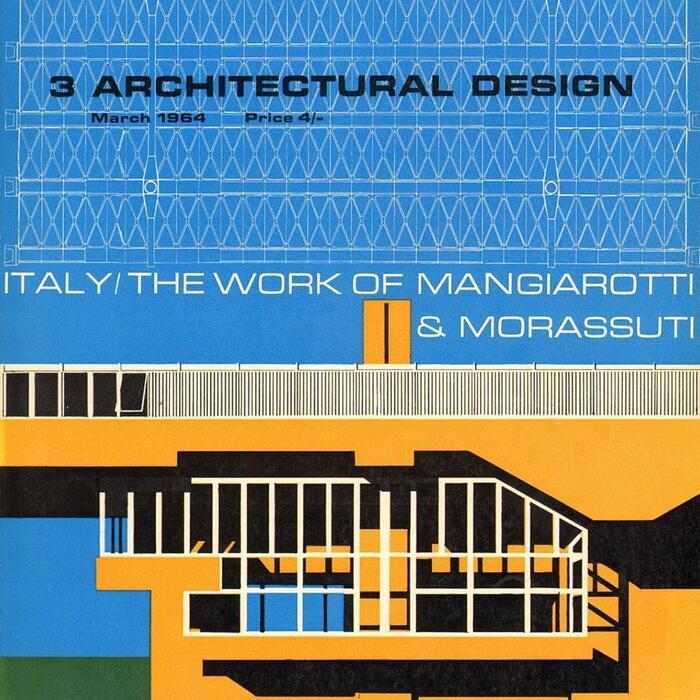

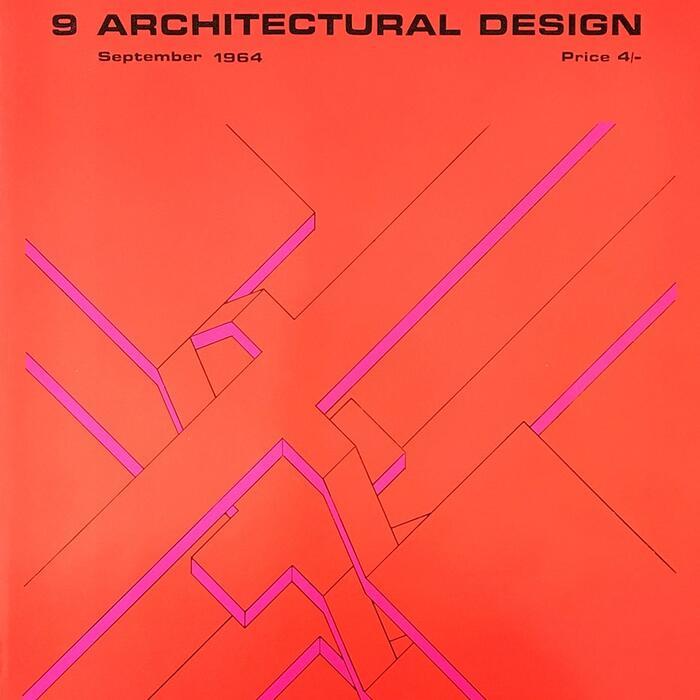

Before he took up the pen in earnest, Ken joined Douglas Stephen’s practice in the early 1960s. This was during his time as technical editor at Architectural Design, where he produced a series of memorable, brightly coloured monthly covers with abstracted architectural themes.

Douglas Stephen was a generous employer and friend, and Ken, then in his early thirties, was entrusted with the design of an apartment building in Craven Hill Gardens, Bayswater, and the supervision of its construction through to completion.

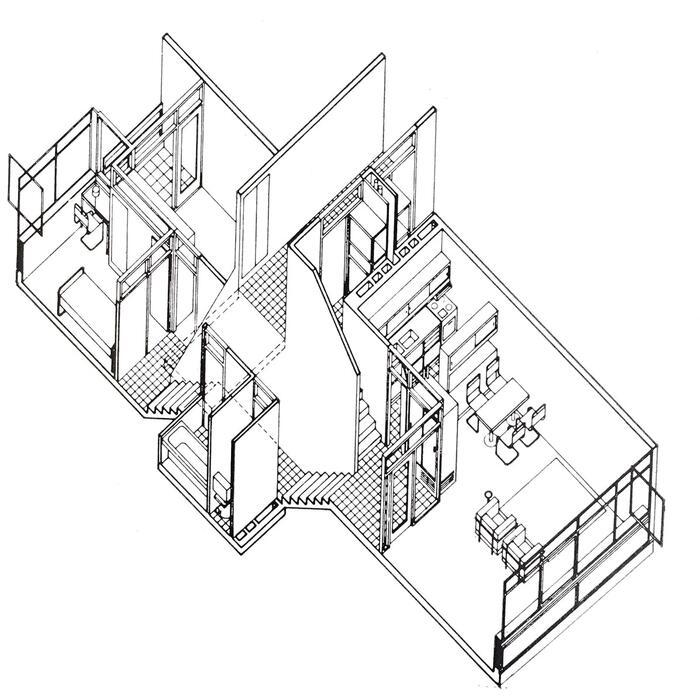

The brief called for a maximum number of two- and three-room maisonettes, to be sited at one end of a central public square, surrounded by nineteenth-century terrace houses.

It is a remarkable work. The exterior of the eight-storey apartment building is strikingly rational, with six stacks of recessed balconies to both long elevations. At the end of the building is a highly articulated entrance core and lift, and stair access tower. The entrance core is ‘tethered’ to the surrounding pavement by a narrow, covered ramp that runs up to the street. In those days, you could imagine a resident arriving on a rainy evening by taxi and making the walk to their door without ever feeling a drop.

Instead of external access galleries, so characteristic of current high-rise practice at the time, Ken proposed wide central ‘public’ corridors, which run the length of the building, from the lift and stair tower to an escape stair at the other end. This is essentially a reference Le Corbusier, and more specifically, the section of the Unité d’habitation.

It is ingenious if complex, and unexpected in the context of the rationalism of the exterior. As students at the AA, ten years before, we had been obsessed with ‘half level’ planning. The advantage was thought to be the omission of ‘dogleg’ stairs and half landings. This enabled spaces to easily ‘swim’ into one another, by means of short single flights. But for a builder, before the dividing partitions are in, equal half levels meant there was always some doubt about where an apartment might end or begin. Ken’s design certainly challenged the contractors. I remember the foreman, faced with these immaculate drawings, shaking his head and remarking, ‘That young Kenny…’ – well, you can imagine the words that might have followed.

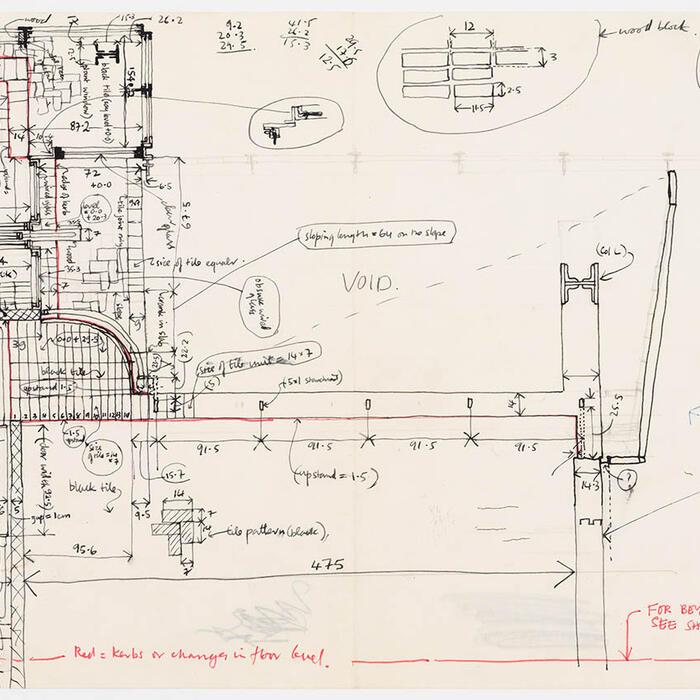

The drawings that Ken provided for the contractors were unusual. Instead of showing floor plans of each maisonette type independently, floor levels, sections and elevations of the building were drawn in their entirety, and in great detail, even down to floor tiling. In a sense they were a description of the completed building – an analogue of the building to be, rather than instructions to a contractor for its construction.

Craven Hill Gardens was completed nearly sixty years ago. It is an impressive work, which I continue to admire, and it richly deserves its 1998 Grade II listing.

John Miller was educated at the Architectural Association and after working as an assistant to Leslie Martin, Colquhoun + Miller was founded in 1961. The practice became John Miller + Partners in 1990 on the retirement of Alan Colquhoun.

Juhani Pallasmaa Back to top

At Machu Picchu

I vividly recall Kenneth Frampton almost running up the steep footpaths and stairs at Machu Picchu on our two visits to this legendary fifteenth-century Inca citadel. I remember him leaning against the semi-circular wall of the Temple of the Sun and silently contemplating the Intihuatana calendar, while surrounded by clouds. I can also see him studying the magnificent polygonal masonry work at Sacsayhuamàn, standing by the experimental farming terraces of the Incas at Moray, and walking in the walled streets of Cuzco, once the capital of the Incan empire, observing the intricately joined stones.

I also recall our forking conversations on architecture and art, history and philosophy, politics and friends during this trip. On our way to see the farming terraces, we discussed the enigmatic statement of the Catalan philosopher Eugenio d’Dors: ‘Everything that is outside of tradition, is plagiarism.’ I had read this provocative sentence in the memoirs of Igor Stravinsky and Federico Fellini, and Ken would later refer to it in his book Labour, Work and Architecture. In a Fellinian spirit, we watched a group of tourists as they danced down the corridor of our tiny train as it wobbled and wound down the steep mountains towards Machu Picchu. Another unexpected experience was a Peruvian bullfight in Lima, at the time bullfights were banned in Catalonia.

Our first visit to the world of the Incas took place after a conference on architectural education at the University of Lima, organised in 2001 by Frederick Cooper, the energetic dean of the architecture school. We happened to lecture in Lima just a few days before the collapse of the World Trade Center in New York. I returned to St Louis on the eve of the catastrophe. Ken was flying the next day to New York. His plane was diverted to Atlanta, and he was obliged to wait several days before he was taken to New York by bus.

Our second visit to Cuzco took place exactly ten years later, in 2011, as jurors for the New Faculty of Engineering of the Technical University of Lima. The competition was won by Grafton Architects, from Dublin, who were later awarded the 2020 Pritzker Prize. The project is an elevated, open and continuous multi-level structure that echoes the ambience of the Inca citadel, embraced by clouds.

Juhani Pallasmaa is an architect, professor emeritus (Aalto University, Helsinki) and writer.

Miscellaneous marvels Back to top

Soane’s collection is rich and diverse, but there are some particularly marvellous treasures to see. Beautiful natural curiosities – like ornaments cut from ash trees and ‘antediluvian snails’. Rare Peruvian pottery from the pre-Columbian period. And the sarcophagus of Pharaoh Seti I. You’ll discover all these objects – and plenty more oddities – as you follow this trail.

Miscellaneous marvels pdf Back to top

title Back to top

On Earth, our view of the illuminated part of the Moon changes each night, depending on where the Moon is in its orbit, or path, around Earth. When we have a full view of the completely illuminated side of the Moon, that phase is known as a full moon.

On Earth, our view of the illuminated part of the Moon changes each night, depending on where the Moon is in its orbit, or path, around Earth. When we have a full view of the completely illuminated side of the Moon, that phase is known as a full moon.

On Earth, our view of the illuminated part of the Moon changes each night, depending on where the Moon is in its orbit, or path, around Earth. When we have a full view of the completely illuminated side of the Moon, that phase is known as a full moon.

Flaxman at the Saone pdf

Zhu Tao Back to top

Frampton = Frankfurter + French Fries

Kenneth Frampton once told me that ‘as an architectural intellectual, I suppose, one eventually must choose between Frankfurters and French fries. Peter Eisenman has chosen French fries, and I, the Frankfurter.’

This was not literally a question of what to eat. He was applying an old joke of critical theory to architecture. On the philosophical spectrum, Frankfurters, like the food itself, are the seriously uptight – Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse, Habermas. French fries, on the other hand, are the provocative and ironic – the Foucaults, Derridas, Bartheses and Deleuzes of the world. Salty, stylish, bendy, more-ish. Frankfurters were unhappy with how the French Fries ‘aestheticised’ everything. French fries complained that Frankfurters were too ideologically stiff.

But to give my former teacher more credit, I don’t think he has ever really subscribed to either culinary camp. Kenneth Frampton is far more complicated than his self-description. Certainly, compared with Eisenman, he is very Frankfurter-ish, insisting that architecture only acquires meaning when an innovative formal project aligns with a progressive social project. But, compared to Manfredo Tafuri, Frampton might appear too French-fried. For if, following Tafuri’s logic, all progressive social projects are doomed to fail, why does Frampton still maintain faith in the redemptive power of architecture’s formal beauty?

Among Frampton’s published works, I would say that A Critical History tastes Frankfurter-ish, while Studies in Tectonic Culture and his numerous essays promoting ‘critical regionalism’ contain more of a ‘French fries’ flavour. One can also identify in Frampton’s global readership two groups of the gluttonous: scholars devouring the former and architects chewing over the latter. The former offers a new kind of historiography; the latter inspires one to pursue good design. In a way, his career has fed us all – and through him I have learned to treat architecture as a balanced meal of both protein and carbs.

Zhu Tao is a former student of Kenneth Frampton. He teaches architecture at the University of Hong Kong and practices architecture in China. He received his Master of Architecture and PhD in Architecture History and Theory at Columbia University.

Header image credit: Kenneth Frampton, c 1981, the year ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’ was first published, photo Silvia Kolbowski. Kenneth Frampton fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, gift of Kenneth Frampton