Search results

Gilding the frame Back to top

Once the compo was complete the frames returned to the Soane Museum for gilding. First, consultant specialist frame conservator Clare Kooy-Lister applies a layer of pigment and rabbit skin glue over the whole frame, which will enhance the richness of the gilding. Then some parts of the frame – those that will catch the light – are over-painted again with a second, different coloured solution. When this has dried the frame is ready for the application of the gold leaf, which is so thin and light that a special guard is used to prevent draughts blowing it away as it is delicately lifted with a brush and placed on the frame. Once applied the gold is gently pressed down with soft cotton wool to ensure it adheres properly. The new gold is so bright that it disguises the delicacy of the compo decoration and would overwhelm the artwork if left as it is. The solution is ‘toning’, which involves the application of a weak solution of rabbit-skin glue which is then carefully rubbed and distressed to bring out the shape of the compo decoration and give the gold a patina that enables the finished frame to harmonise with its older neighbours once re-hung in the North Drawing Room.

Preparing the drawings Back to top

While the frames were being recreated, the two sketches were removed from their modern card window-mounts and surface-cleaned by the Museum’s consultant Paper Conservator, Lorraine Bryant. She prepared pale blue mounts for them, replicating the subtle colour shown the 1830s watercolour by applying a matching watercolour wash border with a broad sable brush to a 100% cotton rag board. Several layers of blue wash were gradually applied to the dampened board to avoid tidemarks – it took several attempts to achieve two perfect mounts – before the drawings could finally be mounted and re-framed.

Today, this delightful pair of sketches hangs once again in the North Drawing Room to complete the authentic arrangement of pictures on the east wall as it was at the end of Soane’s life.

For more information about the work of Joseph McCarthy Mirrors and Frames visit www.josephmccarthy.co.uk

Creating the laths Back to top

In this film clip Neil England of England’s Ornamental Plastering describes the process of reconstructing the plaster ceiling ornament, beginning with the sunburst centrepiece, surrounding a cast of Apollo’s head cast from one in Soane’s collection.

The sunburst is composed of plaster laths (thin strips of material covered in plaster) in three layers and Neil must work high up in a tiny cramped space from scaffolding, reaching above his head as he trims and fits the laths. The laths themselves needed to be so thin that the only material that could be used to form them was cotton lint (as Neil observes ‘rather like your grandmother’s curtains) dipped in plaster. Each plaster ray has to be trimmed to the precise size specified in the complex architects drawing – itself the product of a huge amount of research to get the dimensions precisely right.

Chapter 2 Back to top

Nam tincidunt, tellus eu efficitur tincidunt, sapien risus ultricies mauris, lobortis pretium arcu tortor nec nisl. Donec lobortis sed libero vel dignissim. Nam lacinia dui at tortor fermentum aliquet. Nulla consequat eu tortor vel congue. Sed turpis ex, feugiat nec felis dictum, vestibulum commodo eros. Praesent lobortis laoreet tortor a fringilla. Sed metus leo, molestie nec facilisis id, facilisis et eros.

Sticking up the laths Back to top

Neil checks each lath fits before sticking it in place using lime and alpha plaster (top quality casting plaster, which is very fine, hard and strong) – just as the workmen from Thomas Palmer and Son who made the original ceiling for Soane would have done. Neil comments that this is one of the most complex ‘stick ups’ he has ever carried out. Each lath must be placed absolutely precisely because if it is so much at 1mm out of place that will show when the next one is put in place. As soon as the lath is in position Neil must quickly clean off surplus plaster and check that it lines up precisely.

Once the sunburst at the centre of the ceiling is complete Neil moves on to the fixing of the decorative elements at the four corners of the dome, each one composed of three elements – eagle, snakes and a leaf, each cast separately and transported as three pieces to the Museum for fixing. They were carved by EOP’s sculptress Sarah Mayfield and then cast using high Alpha casting plaster in a mix probably a bit, as Neil says, ‘tougher’ than the one used by Soane’s men but otherwise just the same.

This was a very complex project involving years of research into sunburst ceilings and carved snakes and eagles in other locations and Apollo heads and leaves in Soane’s collection. The geometry of the ceiling itself required a huge amount of work to get the dimensions just right and to calculate exactly how the ornaments worked. In the end, as Neil England says at the end of this clip, everyone did their very best working with extraordinary precision to achieve a result as close to how the ceiling looked in Soane’s time as it could possibly be.

Painting the window Back to top

In this film clip Jonathan Cooke begins with the full-scale preparatory drawing, in pencil, for the window. In working on this drawing, with a copy of one of Reynolds’ preparatory paintings for the New College window to hand, he realised that William Collins, in making his copy, adjusted the figures to make them fit the dimensions of the window. If he had reproduced the figure of Charity directly from Reynolds’ original design one of the glazing bars would have passed directly through her face. To allow for this the figure had to be moved to the right and repositioned. Jonathan’s preparatory drawing took a year to produce, working from time to time and gradually building it up. As Jonathan says, it is not a work of art but a working drawing and therefore some parts are not fully drawn up, for example borders where it is only necessary to draw a small part of a repeated motif to provide enough information to paint the glass. A scroll is drawn in detail on one side just copied and reversed to provide a template for its pair on the other side when the glass is painted.

To begin the painting process Jonathan lays the glass over the drawing so that he can mark key points onto it – for example the eyes and noses of the figures. The drawing is then placed on one side and Jonathan continues his work by drawing free hand onto the glass. As he comments, it is a bit like life-drawing, only working from a drawing rather than a live figure. The process can be slow but is very satisfying.

To illustrate how the painting is done the film shows Jonathan using a sable-hair brush to draw the hair of Charity. The sable-hair softens the drawing and gives it the fine texture of real hair. A nightmare for glass painters is if a tiny hair comes loose from the brush and lodges in the paint unnoticed – the oil paint will dry so slowly around it that it leaves a tiny visible halo!

History of the project Back to top

Although Soane wanted his house and collection to be preserved exactly as they were after his death, over the years, curators have made significant alterations to some areas. Though well-meaning, these curators sometimes changed things that Soane would not have wanted changed.

The entire second floor, where Soane and his wife had their bedrooms, and later the spectacular Model Room, was turned into an apartment for the curator. Then into offices. His ‘Lobby to the Breakfast Room’ was lost, and a wall in the Dome area was knocked down, amongst other changes. With the Museum needing space for staff and storage, it seemed very unlikely that these significant losses could ever be reversed.

This all changed with the purchase of No. 14 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, bringing it into the use of the Museum for the first time. The staff offices were moved into No. 14 in 2009, meaning that we could finally start restoring the spaces they had occupied to their former glory. The Research Library and exhibition gallery also moved, allowing their old locations in No. 12 to be turned into new facilities for our visitors. After a very successful fundraising campaign, work began in 2011.

Pigment and brushes Back to top

The technical side of recreating the window was particularly demanding. As Jonathan says ‘we have not painted glass this way for nearly 200 years’ and what is required resembles porcelain painting technique. He spent time finding out how to paint as Collins did, not only by examining examples of his work but also by reading late Georgian treatises. The paint is just powdered pigment – it’s what it is mixed with that is critical. In medieval times painters mixed paint with urine or wine but by the 19th century they were using a much wider variety of solutions from water and vinegar to different kinds of oils, which were used in a way that is difficult to replicate today. The manuals indicate that what Collins would have used was probably turpentine and Amber oil (interestingly, this is the oil that Salvador Dali always used). However, when Jonathan tried to use it, it didn’t work well, and he had to find an alternative. The project required continuous experimentation throughout to achieve the desired result. This included trying out various brushes with different kinds of hair. In traditional painting artists tend to use badger-hair brushes but for this purpose Jonathan found badger too rough and scratchy. In the end, after trying many different types, he found that the ideal brush to soften and stipple the surface was a Police Fingerprint brush– made of squirrel hair! As Jonathan concludes, glass painting is all about the technique: if you understand the materials and how to apply them then you can achieve then you can do it!

Today, visitors can see the magnificent recreated window reinstalled in the Tivoli Recess exactly as Soane intended, a tribute to the unique skills of all those involved.

Find out more about Barley Studio at www.barleystudio.co.uk. A collection of useful pdfs covering the recreation of this window and other projects can be found on this page.

Find out more about Jonathan Cooke www.jonathancookeglasspainter.com

Phase I Back to top

The first phase was to transform No. 12, and saw the creation of the Soane Gallery, a dedicated space for temporary exhibitions, and the custom-built Soane Shop. We improved facilities for our visitors with a new cloakroom and toilets, and two new lifts made us more accessible. We were also delighted to open the John A and Cynthia Fry Gunn Conservation Studio ensuring the proper care our 45,000 objects need.

Phase I was also used as an opportunity to restore the Tivoli and Shakespeare Recesses on the Museum’s main staircase in No. 13. They were both also altered after Soane’s death, with the Tivoli Recess becoming a toilet! These unusual spaces are now returned to their original dimensions and their beautiful decoration reinstated.

Architecture of Resistance Back to top

Researcher and photographer (above): Gregorio Carboni Maestri.

Despite our political incapacity to confront the environmental nemesis of our time, architecture can be pursued as the cultivation of a poetics of construction dedicated whenever possible to the realisation of a ‘space of public appearance’ within which society may still realise some measure of its potential sovereignty. My attempt to posit a viable theory of architecture, not only in terms of an ontology of building, but also with regard to what tectonic expressiveness has been able to achieve over the past half century brings to my mind John Summerson.

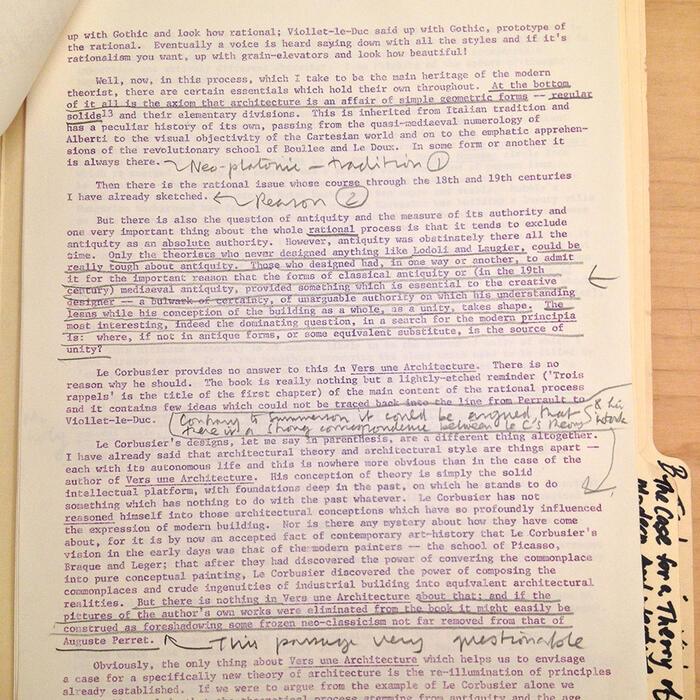

Apart from being the illustrious curator of Sir John Soane’s Museum and an erudite and eloquent scholar, Summerson took upon himself, in the late 1950s, the unenviable task of attempting a theory of modern architecture for the postwar period in a memorable lecture, ‘The Case for a Theory of “Modern” Architecture’, which he gave at the RIBA in 1957. In this lecture he argued that either programmatic functionalism or the syntactical legacy of classicism had to be the source of unity. In his exclusion of any hybrid discourse he seems not only to have revealed his disdain for the Arts and Crafts tradition, with its roots in the vernacular, but also for the erstwhile cosmopolitanism of the interwar British modern movement. With the possible exception of Le Corbusier and Viollet-le-Duc, Summerson appears to have been largely disinterested in anything that lay beyond the confines of his island nation.

In today’s inter-connected, globalised world, such provincialism is no longer viable, even if it has led to some of the country’s most talented architects completing their best work abroad. Yet if we are to cultivate an architecture of resistance to our compulsive commodification of the environment, it is to the earthwork that we must look as the means of achieving a significant transformation of a given site so that a ‘space of public appearance’ might spontaneously emerge.