Search results

Towards a Critical Regionalism Back to top

The publication of ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance’ virtually coincided with the first formulation of postmodernism via Jean-François Lyotard’s book The Postmodern Condition, published in French in 1979. The advent of the postmodern condition would find its cultural echo in the stylistic postmodernism of the first full Architecture Biennale, staged in Venice in 1980. This exhibition was curated by the Italian architect Paolo Portoghesi under the eclectic slogan ‘The End of Prohibition and the Presence of the Past’.

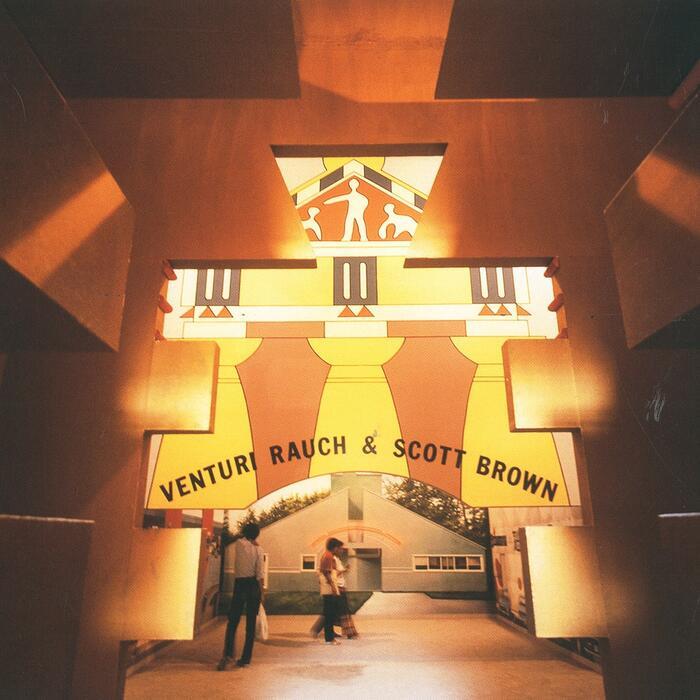

It is telling that its centrepiece, the so called Strada Novissima, comprised a sequence of shopfront facades designed by a rising generation of star architects, modelled after the sophistry of Robert Venturi’s ‘decorated shed’ as advanced in his book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture of 1966. Perhaps fittingly, the ‘new street’ was erected by the scene builders of the Italian film industry.

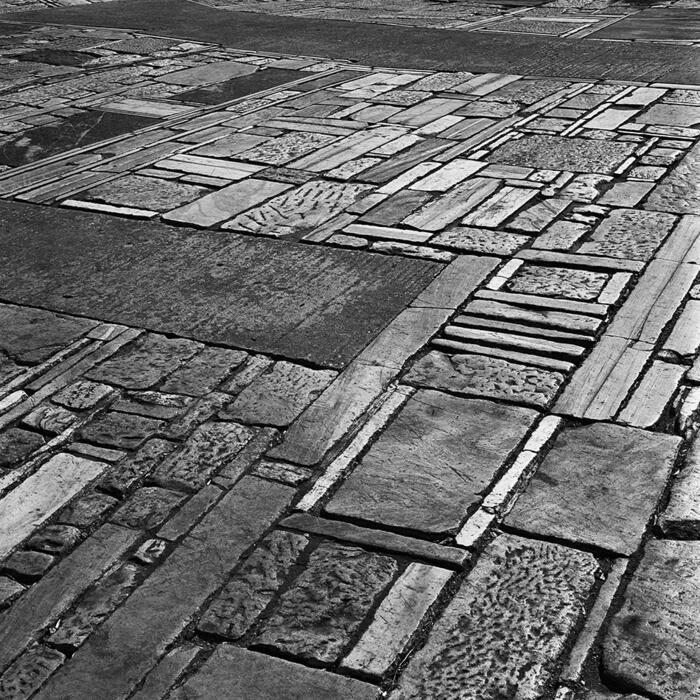

It was this scenographic provocation that prompted ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’, which was first published in Hal Foster’s anthology The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays in Postmodern Culture. I took the term ‘critical regionalism’ from Alexander Tzonis and Liliane Lefaivre’s 1981 text The Grid and the Pathway, in which they made a comparative critique of the two most prominent Greek architects of the 1950s, comparing the trabeated forms of Aris Konstantinidis to the tactile topographic approach of Dimitris Pikionis, particularly the latter’s undulating landscape on the Philopappos Hill, built adjacent to the Athenian Acropolis in 1959. Influenced by Tzonis and Lefaivre, I developed my critically regionalist manifesto as a stratagem with which to offset the impact of universal civilisation by stressing the crucial importance of the place-form as a ‘space of public appearance’.

Phase II Back to top

The most complex, ambitious and exciting phase of the project was completed in 2015. The rooms where Soane and his wife lived and slept – the private apartments – have been fully restored. Visitors to the Museum can once again explore Soane’s collections of models, drawings, watercolours and stained glass as he intended. Until the restoration, many items from these rooms were in storage. There are six rooms on the second floor, including Mrs Soane’s Morning Room, the Bath Room, the Bedroom, the Oratory and the Book Passage. The centrepiece, however, is the Model Room. It displays 40 of the finest architectural models in Soane’s collection, many on an unusual three-tiered model stand which dominates the room. The models he displayed include those of exquisite buildings from the ancient world, in both ruins and their full glory. Alongside these are Soane’s own models, which he used to showcase his innovative methods and teach his students.

The Earthwork Back to top

In my view the earthwork and its extension into the landscape, embodying a cosmogonic transformation of the site, has the potential today of constituting the core of a resistant architecture. This is an architecture that is capable of mediating our compulsive commodification of the environment by virtue of integrating a building into its site rather than merely proliferating yet another free-standing aesthetic object unrelated to either its site or to other objects in its vicinity. This idea is related to the Semperian concept of the Bekleidung, in that the cladding of a building may simultaneously both reveal and conceal its basic structure. In his essay, Gottfried Semper identified the ‘Four Elements of Architecture’ as: the earthwork elevating the hut above the ground, the hearth recessed into the earthwork, the framework and roof and the ‘woven’ infill wall providing the basic enclosure. All of these elements were present in the Caribbean hut that Semper first witnessed in the Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851. With regard to my appraisal of canonical archi-tectonic works of the last half century, we may condense Semper’s four elements into the earthwork and the roofwork.

Perhaps the first intimation of the tectonic in the modern tradition is to be found in the work of Le Corbusier, where the earthwork–roofwork dialectic, appears in his weekend house at La Celle-Saint-Cloud, of 1935, where the earth is mounded up over the house thus covering its vaulted, shell-concrete roof with turf.

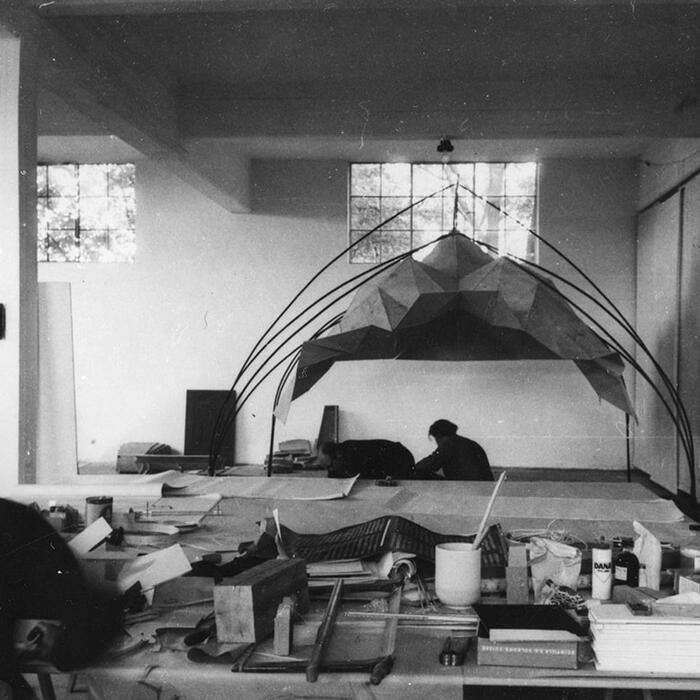

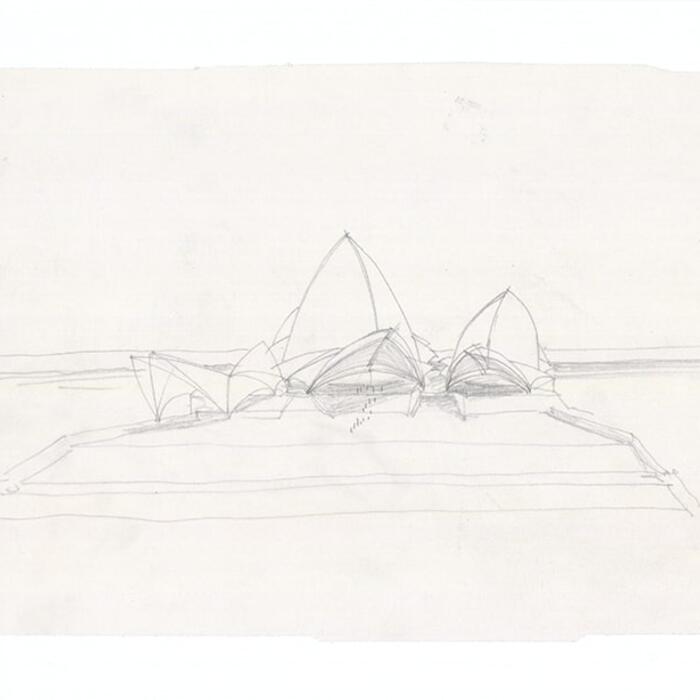

But it is after the the Second World War when the earthwork–roofwork emerges as a topographic tour de force in Jørn Utzon and Tobias Faber’s 1947 competition entry for the London Crystal Palace site. This project was an early manifestation of Utzon’s life-long, preoccupation with his transcultural pagoda/podium paradigm which attained its ultimate expression in his 1957 winning entry for the Sydney Opera House, a duality which he returned to more modestly in his Bagsværd Church, completed outside Copenhagen in 1976.

Transcending Form Back to top

Across the Atlantic, the heroic Brazilian tectonic tradition in reinforced concrete was inaugurated in 1955 by the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, designed by Affonso Reidy. Something similar can also be found in Paulo Mendes da Rocha’s Athletico stadium in São Paulo of 1958, which combines a suspended wire-cable roofwork with a cantilevered reinforced concrete earthwork. In this example, we have a typically Brazilian ‘space of public appearance’, located in downtown São Paulo, and open on its perimeter so as to encourage the infiltration of passers-by. As the academic and educator Maria Isabel Villac has remarked, this building aspires to a wider political significance, transcending its dynamic form. At the same time, one is struck not only by the elegant ingenuity and clarity of the structure but also by its inherent economy.

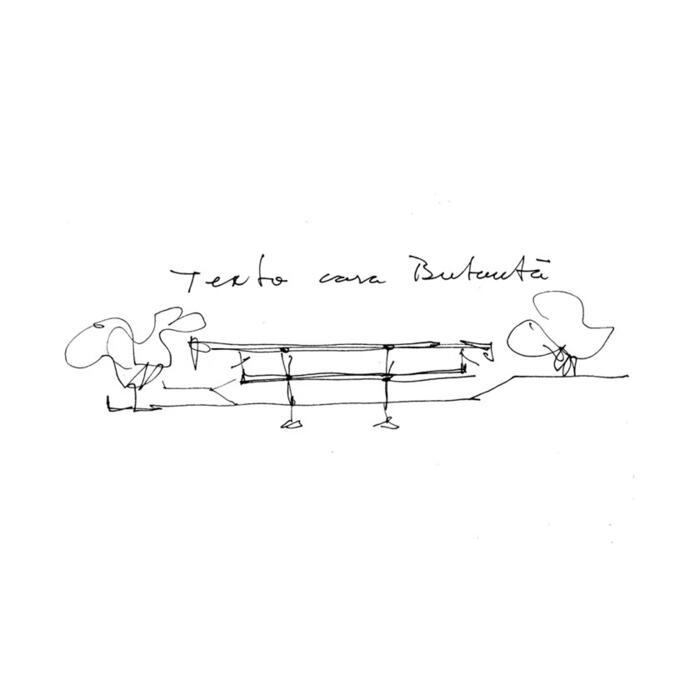

Another example is Mendes da Rocha’s own house built in the Butantã, a suburb of São Paulo, in 1964. Apart from the earthwork–roofwork paradigm, the house is a family dwelling conceived as a ‘space of public appearance’. This is surely the most striking aspect of its plan, where top-lit bedrooms are set between an entry foyer on one side and living/dining volume on the other. Downstand beams carrying floor and roof are each cantilevered in both directions from only four supports. This allows the house to be economically suspended above the earthwork, bounded by a berm and a free-standing concrete wall within which automobiles are parked under the house. In this way, the house becomes a built demonstration, as it were, of Mendes da Rocha’s polemic that ‘a house is a public building’.

A similar territorial imagination is evident in the mega-form that Mendes da Rocha projected for the outskirts of Paris in 2008 to house an athletic campus to be built as part of a French bid for the 2012 Olympic Games. This earthwork was conceived as a gigantic podium, crowned by a roofwork of stadia that would have been perceivable as a major intervention within the megalopolis that surrounds the city on every side.

Phase III Back to top

Phase 3 was completed in summer 2016, and the new spaces opened to visitors on Tuesday 13 September 2016 to much fanfare. This final phase focused on the altered spaces in the centre of the No. 13. We reinstated the ‘Lobby to the Breakfast Room’ and refurbished the Catacombs in the basement below. 10% of our artworks and objects were restored and put back in their original positions, so that visitors can once more enjoy the wonderful displays as Soane intended them. We created a new flexible space for temporary displays, events and installations called The Foyle Space which has taken over a room at the back of No. 12 which was actually part of No. 13 since it was re-built and knocked through into the Dome area in the late nineteenth century. Soane never intended it to be part of his Museum. The Space has been inaugurated as part of our exhibition Marc Quinn: Drawn from Life and it now offers us exciting ways to engage with Soane and his legacy.

The Museum now also has full step-free access.

Architecture of Cultural Spirit Back to top

In terms of architectural culture, Dublin has risen to the fore of late, having been influenced over the last half century by such luminaries as Mies van der Rohe, Louis Kahn, Alvar Aalto and James Stirling, and by the teaching in the 1970s of Ed Jones, Su Rogers and John Miller at the Royal College of Art. This heritage, which was independently cultivated within the architectural faculty of University College Dublin under the charismatic leadership of Shane de Blacam, led to the emergence of Group 91, which worked on the restoration of the Temple Bar district in Dublin in the early 1990s. The two most fertile practices to emerge from this experience are Sheila O’Donnell and John Tuomey, and Grafton Architects, founded by Shelly McNamara and Yvonne Farrell. The latter practice came to international prominence after winning a limited competition to expand the leading Italian business school, the Luigi Bocconi University in Milan. Theirs was the only design that was able to meet the requirement of providing an aula magna, or great hall, that was equally accessible to both university and city. Completed in 2008, this ‘space of public appearance’ marked the beginning of their penchant for using wide-span, cantilevered reinforced concrete construction.

Following this, Grafton were able to build on their reputation of expertise in the design of business schools. This led to the design and realisation of a brick-faced business school in Toulouse, and their Marshall Building for the London School of Economics, situated on a prominent site on the southwest corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. It is surely symptomatic of the current prowess of Irish architecture that this is the second work to be commissioned by the LSE from the Group 91 generation, the first being a student centre built to the designs of O’Donnell + Tuomey on a tight site near the northern end of the campus. For Grafton, an even more unequivocal ‘space public of appearance’, this time in their native Ireland, is a project for the Dublin City Library. This will be built behind a Georgian terrace facing onto Parnell Square in the centre of the city and will see a heroically cantilevered reinforced concrete structure soaring above the reading room in recognition of the one art, above all others, that embodies the essential cultural spirit of the Irish nation.

Header image credit: Kenneth Frampton, c 1981, the year ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’ was first published, photo Silvia Kolbowski. Kenneth Frampton fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, gift of Kenneth Frampton

Napoleonica in the Soane Back to top

Many Britons – including Keats, Byron, and Hazlitt – were fascinated by Napoleon. And so was Sir John Soane. Soane admired Napoleon’s influence on Parisian architecture, and added many Napoleonic items to his collection. You’ll discover them on this trail.

Napoleonica download

Why does this happen? The shape of the Moon isn’t changing throughout the month. However, our view of the Moon does change.

The Moon does not produce its own light. There is only one source of light in our solar system, and that is the Sun. Without the Sun, our Moon would be completely dark. What you may have heard referred to as “moonlight” is actually just sunlight reflecting off of the Moon’s surface.

The Sun’s light comes from one direction, and it always illuminates, or lights up, one half of the Moon – the side of the Moon that is facing the Sun. The other side of the Moon is dark

On Earth, our view of the illuminated part of the Moon changes each night, depending on where the Moon is in its orbit, or path, around Earth. When we have a full view of the completely illuminated side of the Moon, that phase is known as a full moon.

But following the night of each full moon, as the Moon orbits around Earth, we start to see less of the Moon lit by the Sun. Eventually, the Moon reaches a point in its orbit when we don’t see any of the Moon illuminated. At that point, the far side of the Moon is facing the Sun. This phase is called a new moon. During the new moon, the side facing Earth is dark.

Emilio Tuñón Back to top

Solamente una Vez

I remember with a certain feeling of nostalgia that month of August 1982, when I joined Rafael Moneo’s office as a collaborator. Rafael was sketching the first drawings for the building of the Previsión Española in Seville. With well-sharpened pencils he stroked the surface of a thin vegetable paper, accurately designing the building’s facade while whispering a well-known bolero composed by Agustín Lara for a friend who decided to join a religious order. I have spent years recalling the exciting first moments in Moneo’s office, during that hot month, in which Rafael recommended that we learn ‘to see the world through the eyes of architecture’. But above all I remember Rafael, absolutely relaxed and drawing, and at the same time singing this bolero – itself a beautiful song that spoke to a total dedication.

Memory is capricious. Sometimes it fixes scenes and events in our head that, being inconsequential to others, can shape the way we understand the world. Over the years, this almost domestic image has been fixed in my own memory as a kind of initiatory moment for me as an architect. Over time this vision of the master, slowly sliding his pencil across the paper, has come to be a kind of allegory for me, in its staging of the dedication that architecture requires. This dedication is, without doubt, present in the committed and honest attitude that Rafael Moneo has always maintained with architecture. In my memory, when Rafael was drawing that facade and whispering those verses, he was making present his interests as an architect. These interests have always been characterised by a permanent oscillation between an architecture connected to the intellectual concerns of the world and an architecture in intimate contact with reality. And it is precisely this way of understanding architecture, of approaching the discipline, which has served as a model for several generations of Spanish architects, opening the doors to a generous way of understanding architecture, and by extension, opening the doors to a committed way of understanding the world.

Emilio Tuñón Álvarez is a Spanish architect. His practice, Mansilla + Tuñón Architects received the 2014 Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts from the Spanish Ministry of Culture. He worked with Rafael Moneo from 1982–92.

Ricardo Flores & Eva Prats Back to top

To be Part of the Whole

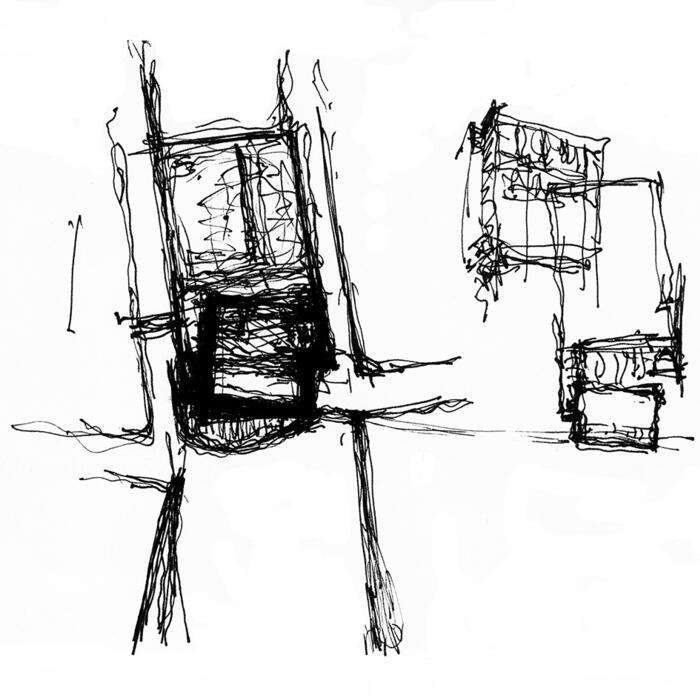

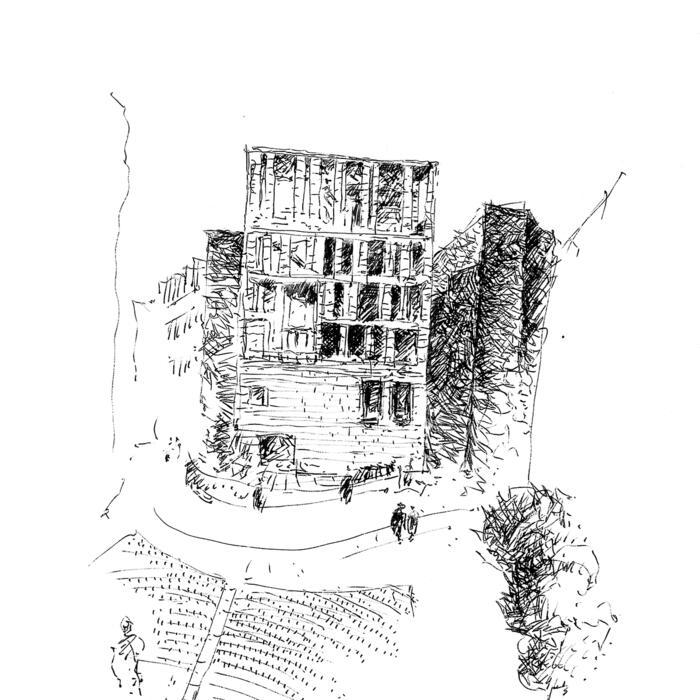

For Rafael Moneo, hand drawing is a driving force to think further, something present in all stages of his projects: in the initial sketches, quick drawings that catch and fix first intuitions, or in his plans, which allow us to visit the work through them. To look at these plans is to walk through his architecture and the succession of connected scenes. The hand with the pencil has travelled through these same spaces back and forth hundreds of times before us, until the articulation between them is so intense and at the same time so simple that the passage from one to the other becomes both natural and surprising at the same time.

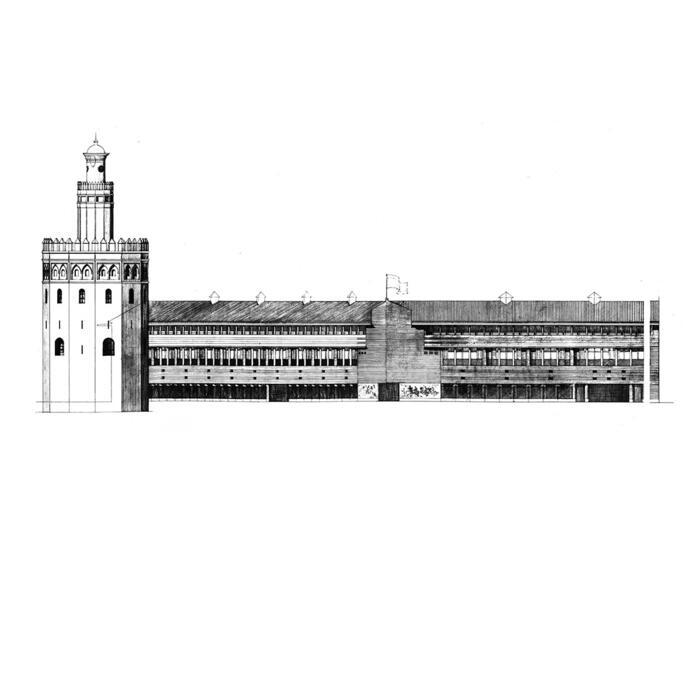

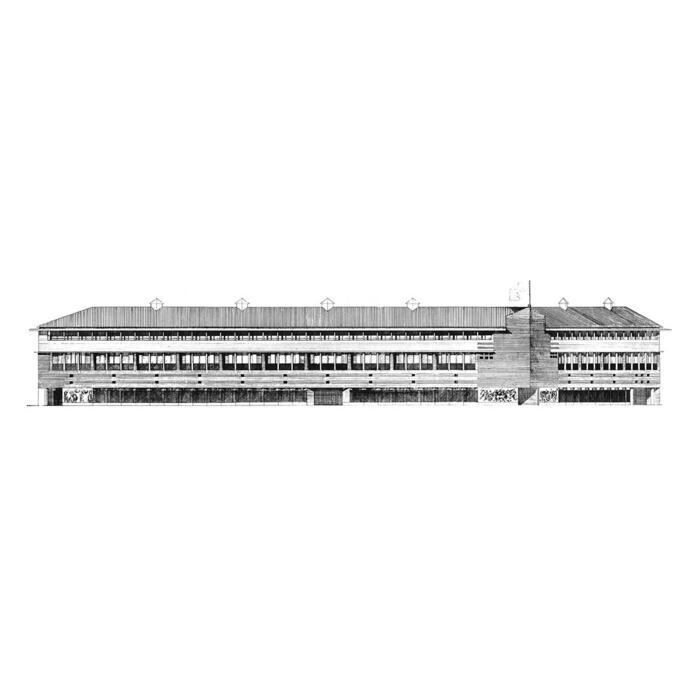

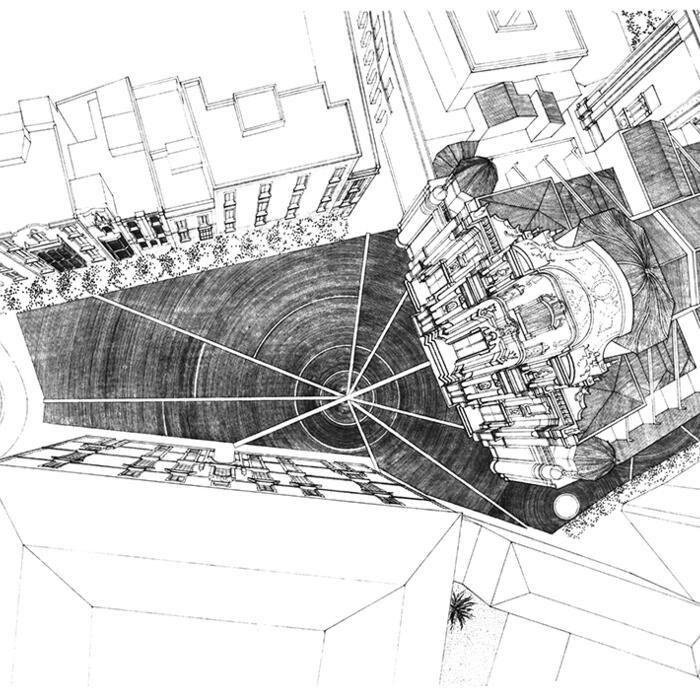

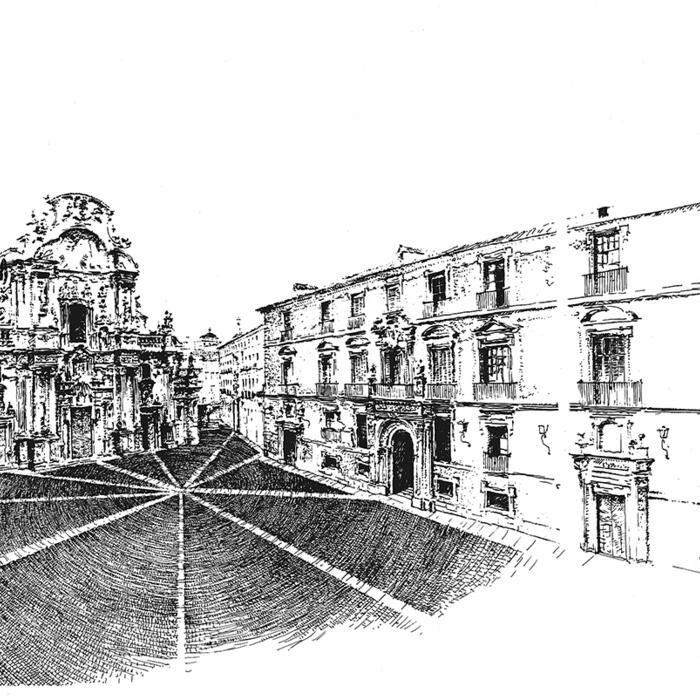

But above all, the axonometric drawings are the ones which trap us: always from a different point of view, it seems that the architect has asked the project: how do you want to appear? Axonometric drawings such as the Murcia City Council extension immerse the observer instantly in a world from which it is very difficult to get out. The project disappears into the immensity of the drawing, and that is precisely what the building wants: to be part of a square and a church, of pavements, windows and cornices and the entirety of Murcia and its surroundings. Everything, city and squares, are contained within it.

These drawings, capable of expressing so many things, are a kind of language for a conversation. One can read in them different stories related to our own personal experiences, and they become interesting objects between the people and the subjects, allowing for a conversation. In the studios of the architecture schools, Rafael Moneo’s drawings, like those of other masters who float over the classes, become these objects about which one can discuss, they always help us to exchange.

Ricardo Flores and Eva Prats founded Flores & Prats in Barcelona in 1998, a studio that combines design and construction practice with an intense academic activity.

London in the Soane Back to top

Explore London through Soane’s collection. See its buildings: those still standing, long vanished, imagined and fragmentary. Come face to face with the city’s artists and architects, kings and heroes, rogues and adventurers. See the city’s greatest events – and the day-to-day lives of its people.