Search results

Sketches, dreams, visions Back to top

Instead of clinging to the funeral towers of metropolitan finance, ours to march out to newly ploughed fields to create fresh patterns of political action, to alter for human purpose the perverse mechanisms of our economic regime, to conceive of fresh forms of human culture…we must erect a cult of life; life in action, as the farmer and mechanic knows it, life in expression as the artist knows it: life as the lover feels it and the parent practices it: life as it is known to men of good will who meditate in the cloister, experiment in the laboratory or plan intelligently in the factory.

Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities, 1938

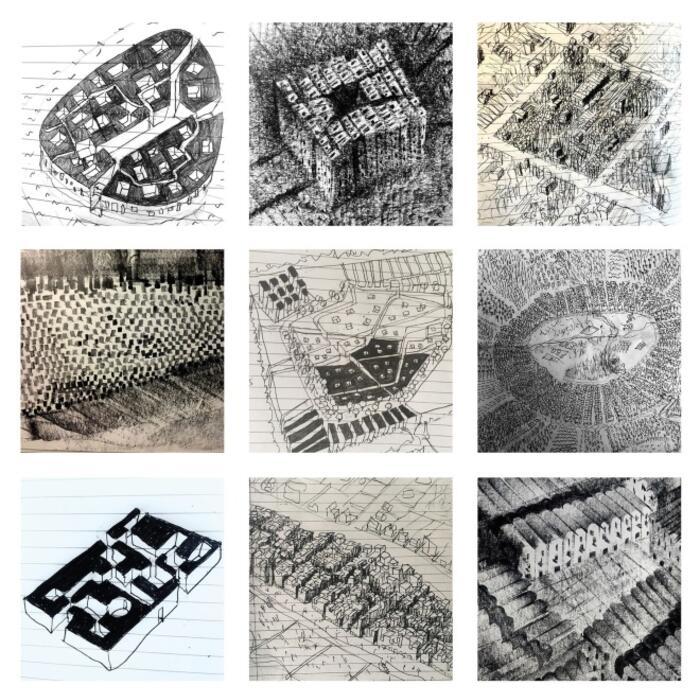

I am an inveterate sketcher, and it’s interesting to reflect with hindsight how little dreamy visions and sketches – thoughts produced in a reflective moment – find their way from time to time, quite often in fact, into our built work.

In this final section I would like to share some ideas from my sketchbooks – some thoughts and visions for our future. Architectural practice, the making of buildings in the here and now, demands that to a significant extent, we work within the programmatic and technical constraints, prevailing societal norms and ultimately the illogic of our neo-liberal economy and cultural system. By contrast my sketchbooks (and my work in academia) have provided me with a space to dream a little, to be speculative, theoretical, to cut loose and, in answer to Lewis Mumford’s heroic rallying cry, to wonder about a different kind of architecture, urban form and society.

My ‘One year 365 cities’ project (pictured above) was an attempt to design a city a day for a year, resulting in numerous short experiments in urban form, unusual materials and imagined lifestyles. Among these ideas is ‘100 mile city’, a project to encircle London with a new street-based linear city of factories, public build¬ings and 2 million houses. Another idea that emerged from the project is Village V/K 3C, a self-sufficient farming cooperative village in rural Wiltshire built out of earth from the ground on which it stands.

Most recently I’ve been thinking about an idea, still brewing, not yet fully formed, called 8,000 Mile Island. This idea encompasses the notion of a countrywide aquacultural and maritime industrial revolution that would see a ribbon of tidal barrages, offshore wind farms, giant floating tidal turbines, deep-sea fish and seaweed farms tracing our coastline from the Orkney Islands to the Isle of Wight and back. Such a project would bring renewed prosperity to our decaying, depopulated coastal towns and cities. It also offers a vision of a food and energy self-sufficient UK and an end to the housing crisis.

8,000 Mile Island arises out of a number of questions and observations.

- Could we be energy self-sufficient? We currently import half of our energy, most of it in the form of gas and oil from tin-pot dictators in the Middle East and from our friend in Russia. However, the UK is unrivalled in its potential for generating clean green energy. It is the windiest country in Europe, and it has the most powerful tides in the world – a giant 15 metres tidal range off the Welsh coast.

- Could we be food self-sufficient? Over half of our food is currently transported from overseas. Half of that comes from beyond the EU. The globalised food industry has the UK firmly in its grasp – food mile madness, collapsing biodiversity, small farmers displaced, pesticide run¬off, deforestation. This is a global industry which sweeps aside local, even national interests for maximum profit, and one which is blind to the climate crisis. The UK has an 8,000-mile coastline. Our land area is 95,000 square miles, but our territorial waters extend to three times that. Imagine a revolution in maritime food production.

- The extraordinary Rampion Offshore Wind Farm, located off the south coast and visible from the beaches of Brighton and Hove, currently generates energy for 350,000 homes. It cost 1 billion pounds to build. One hundred wind farms of a similar scale could satisfy the domestic energy requirements of the UK’s 35 million homes. The cost of all these? 100 billion pounds, or the same as HS2. Wind power currently satisfies 50% of our domestic energy consumption. Let’s finish the job.

- Let’s end the housing crisis once and for all. It’s easy. Refurbish 400,000 empty Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses in the midlands, in the north and in our coastal towns, as homes for these new industries’ incoming workforce. Let’s redeploy the million people needlessly employed in housing construction in the south-east to the making of 8,000 Mile Island.

Picture this: build one hundred 400-megawatt off-shore wind farms and range them around our shores. Interlace them with thousands of floating tidal energy turbines out at sea. Construct enormous tidal lagoons in our estuaries. Put miniature community-run, cottage-industry wave power machines and little barrages on rocky out crops and inlets on our shoreline in Cornwall, the Hebrides and Cumbria.

Let’s intersperse these offshore energy industries with enormous seaweed farms. These are already under construction off the coast of Norfolk, North Yorkshire and in the Southwest. Seaweed carbon sinks are Amazonian in their scale, producing food, a source of energy and munching carbon as they go. Give us hundreds of deep-sea coastal oyster beds, mussel farms, fish and lobster hatcheries – floating fish farms in the deep ocean producing hundreds of the thousands of tonnes of food and millions of gallons of fish shit fertiliser for supply to aquaponic farms.

Construct maritime research stations in a necklace around these islands. Link them to our coastal universities, adding to and sharing knowledge of these nascent technologies and processes for the benefit of everyone.

Imagine existing fishing fleets – their local knowledge, their knowhow and equipment co-opted into these burgeoning industries. Employ the infrastructure already existing in the UK’s declining off-shore oil and ship-building industries in Hull, Inverness and on the Clyde, and think of thousands of new jobs in tired old Blackpool, Margate, St Leonards, Southend-on-Sea and Newhaven. Think of the housing ‘industry’ redeployed away from the south-east and charged with saving and restoring hundreds of thousands of empty homes – whole streets and neighbourhoods currently abandoned, in decay, now buzzing with new life, activity and prosperity from the incoming workforce.

Let’s think carefully about how these nationalised industries might make the best of top-down strategic planning, organisation and funding by Central Government combined with devolved management, bottom up, employing local knowledge, practically, usefully and efficiently applied.

Hogarth's 'modern moral subjects' Back to top

William Hogarth (1697 - 1764), An Election I: The Election Entertainment, 1754-55, Oil on canvas.

Renowned English artist William Hogarth (1697–1764) is best known for his series of paintings and engravings which depict ‘modern moral subjects’. Filled with dark humour and bawdy satire, these narrative series mock the excesses of Georgian society and warn of the consequences of moral abandonment. Sir John Soane purchased two of Hogarth’s series, A Rake’s Progress and An Election.

The four-part An Election is based on a real-life election in Oxfordshire between the Whig and Tory parties in 1764, satirising the corruption rife at every level in both camps. In I: The Election Entertainment, the Whigs hold a riotous dinner for powerful friends. The Mayor has fainted after gorging on oysters, a servant empties a chamber pot out of the window into the Tory demonstration outside, and one of the candidates, flirting with a fat old woman, is unaware his wig is being set on fire. In II: Canvasing for Votes, a young farmer is offered bribes by agents of both, and in III: The Polling, mentally unsound and dying or perhaps even dead voters are being brought to the polling, whilst in the background, a coach carrying an allegory of Britannia has broken apart, whilst its drivers, unaware, are absorbed in a game of cards. The final scene, IV: Chairing the Member, depicts a vicious fight erupting as the victorious candidate is paraded through the streets. As well as its political content, An Election is notable as perhaps Hogarth’s finest painted series, filled with still-life details and pastoral landscapes, and represents his desire to be seen as an artist as well as a political satirist.

Displayed behind the picture planes on the north wall, A Rake’s Progress is one of Hogarth’s earlier series, telling the eight-part story of the fictional Tom Rakewell. This young man inherits a fortune from his miserly father, but squanders it, following a path to vice and destruction. In the opening scene, The Heir, Rakewell coldly discards his pregnant, lower-class fiancé Sarah Young, even as he is measured for a new suit. In The Orgy, he is obliviously drunk at the Rose Tavern in Covent Garden, too intoxicated to notice that his pocket watch is being deftly stolen by prostitutes. By the final scene, The Madhouse, after losing multiple fortunes and enduring Debtor’s prison, he lies naked and insane in Bedlam madhouse as a grieving Sarah Young mourns.

Inspectress level membership Back to top

Join several of our Trustees and our closest supporters for more bespoke events, such as dinners in the Museum and small customised events in private or related collections. As a member of the Inspectress Fund, you will have priority booking on events for Patrons’ Circle members, and further access to the Museum outside public hours.

Members of our Inspectress Fund generously make an annual suggested contribution of £10,000. This comprises of £750 of benefit, and a suggested donation of £9,250.

Get in touch via development@soane.org.uk or call +44 (0) 20 7440 4243 to find out more.

Rights and Images Coordinator (Part-time) Back to top

Salary: £23,720 p.a. (£14,232 for 3 days a week)

The Rights and Images Coordinator will assist the team in SME in exceeding Commercial targets for the Museum from commercial activities. It supports all the image requirements across SME including marketing and product photography for e-commerce, as well as supporting image research for product development.

The role will facilitate the processing of commercial and other image requests and will also include re-sizing, cropping, and cutting out images using InDesign or similar software. This will be an excellent opportunity for someone looking for a flexible role to gain experience in how image libraries operate and gain relevant administration experience.

This role would suit someone who is reliable, creative and flexible. You should have a keen interest in Museum collections and the ways in which they can be used in the wider world both academically, artistically, and commercially.

Please see the attached role profile for a more detailed job description and person specification.

To apply: please email your CV to recruitment@soane.org.uk with a covering letter detailing how your skills and experience meet the person specification and include the details of two referees.

Closing date for applications: Wednesday 24 May 2023.

Interviews: Thursday 8 June 2023.

Sir John Soane’s Museum is an equal opportunities employer committed to equality, diversity and inclusion and welcomes applications from all backgrounds

1st story Back to top

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

This is bold text

This is some bold text

This is italic text

This is some italic text

- This is bullet point list one

- This is bullet point list two

- This is bullet point list three

- This is a long bullet point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

- This is number point list one

- This is number point list two

- This is number point list three

- This is a long number point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

2nd story Back to top

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

This is bold text

This is some bold text

This is italic text

This is some italic text

- This is bullet point list one

- This is bullet point list two

- This is bullet point list three

- This is a long bullet point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

- This is number point list one

- This is number point list two

- This is number point list three

- This is a long number point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Quill Pen

Quill pen

In Soane’s time, some pens were made from feathers, also called quills. The best quills come from geese; the feathers used are those from the leading edge of the wings. They were sometimes dried and hardened in hot sand and they were shaped with a sharp knife – a pen knife – to form a nib. This could be fine or broad as required.

Metal pens were also starting to be used in Soane’s time and would be used for finer work. Soane’s Tyringham Gateway sketch was probably made with a quill pen like this one.

The Upper Drawing Office

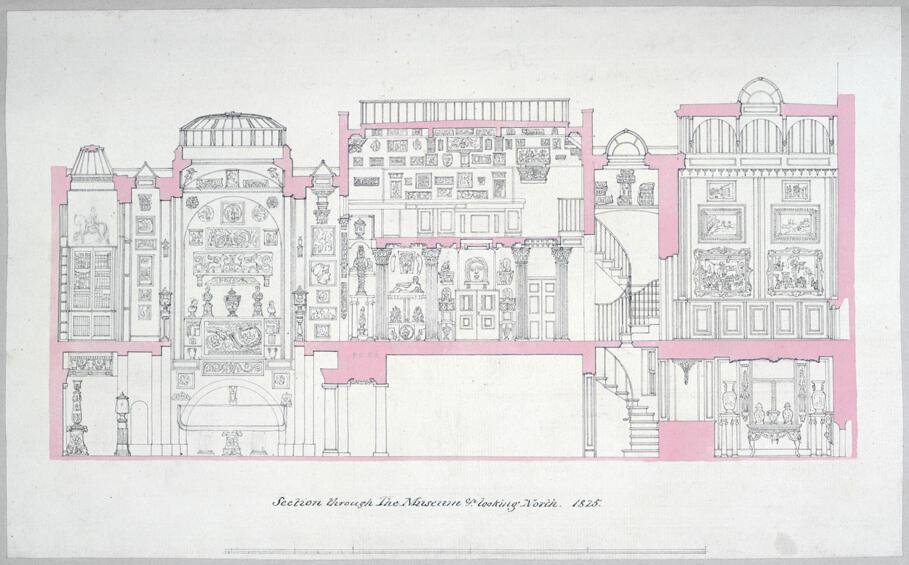

The Upper Drawing Office Vol. 82/33

This drawing, made in 1825, shows a section through the back part of the Museum where Soane’s pupils worked. The areas left white show the Upper Drawing Office, and the office door they used (see also The Little Study). The Office is supported on columns above the area known as the Colonnade which connects the Dome, where you can look down to the sarcophagus, with the Museum Corridor from where the staircase leads to the Office. Light came down in the Office from two skylights above the benches and the walls were hung with plaster casts to instruct and inspire the pupils.

Canaletto’s views of Venice Back to top

Antonio Canaletto (1697 - 1768), Riva degli schiavoni, Venice, c.1734-35, Oil on canvas

Soane purchased three paintings by Canaletto, including the Riva degli Schiavoni, one of the Italian painter’s greatest works, which hangs opposite the doorway to the Picture Room. Depicting an almost photographically-rendered view of the famous promenade in Venice, with the Salute, San Giorgio and San Marco visible in the distance, the painting also gives a snapshot of life in the city, with a myriad of ships moored in the lagoon and figures from all walks of life depicted in immaculate detail. Two further Canalettos, a view of the Rialto Bridge, and a view of the Piazza San Marco, flank the painting on either side.

test chapter 55 Back to top

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

This is bold text

This is some bold text

This is italic text

This is some italic text

- This is bullet point list one

- This is bullet point list two

- This is bullet point list three

- This is a long bullet point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

- This is number point list one

- This is number point list two

- This is number point list three

- This is a long number point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

this is the test chapter

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

This is bold text

This is some bold text

This is italic text

This is some italic text

- This is bullet point list one

- This is bullet point list two

- This is bullet point list three

- This is a long bullet point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

- This is number point list one

- This is number point list two

- This is number point list three

- This is a long number point Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed et finibus nunc. Vivamus volutpat, sapien a placerat fermentum, augue ipsum sollicitudin ipsum, tincidunt venenatis nisi lacus a est. Donec scelerisque mi eget faucibus fermentum. Quisque tristique egestas feugiat. In sodales ipsum nisl, eu malesuada arcu laoreet sed. Morbi id semper turpis, at tincidunt ipsum. Ut volutpat orci enim, nec consectetur ligula maximus eu.

test downlaod

test chapter 2 title Back to top

test body chapter 2

test lower text test

test downloads

test collection title Back to top

test body