Search results

haddonstone-hercules-bust2.jpg Kirstinimage/jpeg46.54 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg46.54 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg46.54 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg46.54 KB

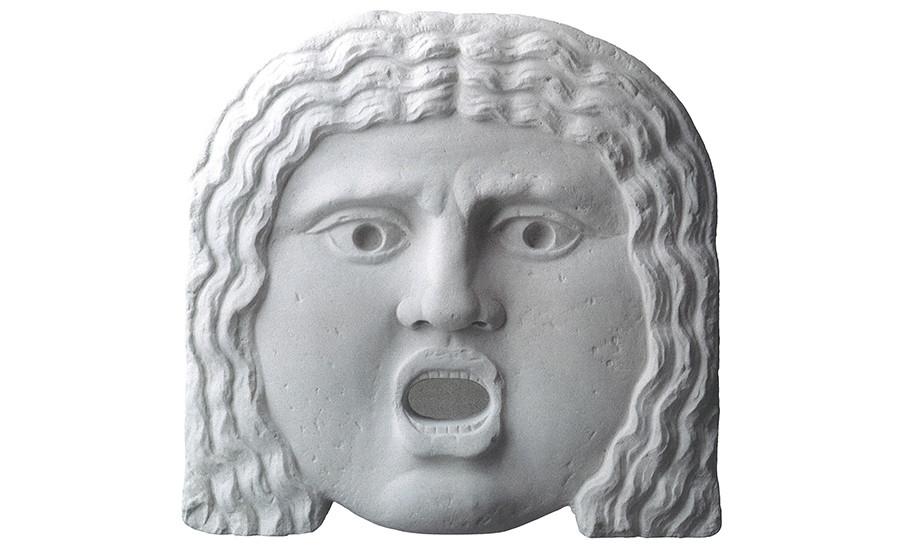

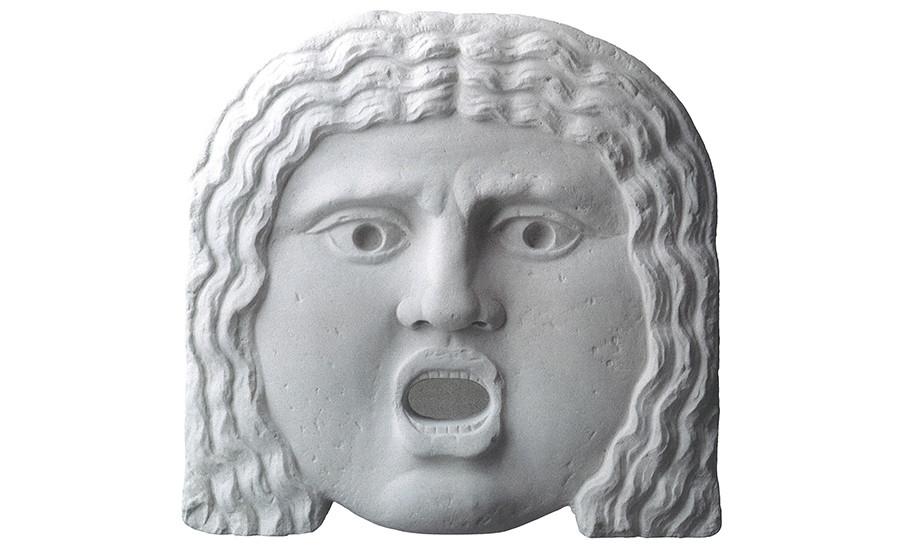

haddonstone-mouth-of-truth.jpg Kirstinimage/jpeg50.89 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg50.89 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg50.89 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg50.89 KB

Q972_SOANE_MOUTH_OF_TRUTH-2.jpg Kirstinimage/jpeg119.36 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg119.36 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg119.36 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg119.36 KB

greyTest_0.png dp_adminimage/png9.94 KB

dp_adminimage/png9.94 KB

dp_adminimage/png9.94 KB

dp_adminimage/png9.94 KB

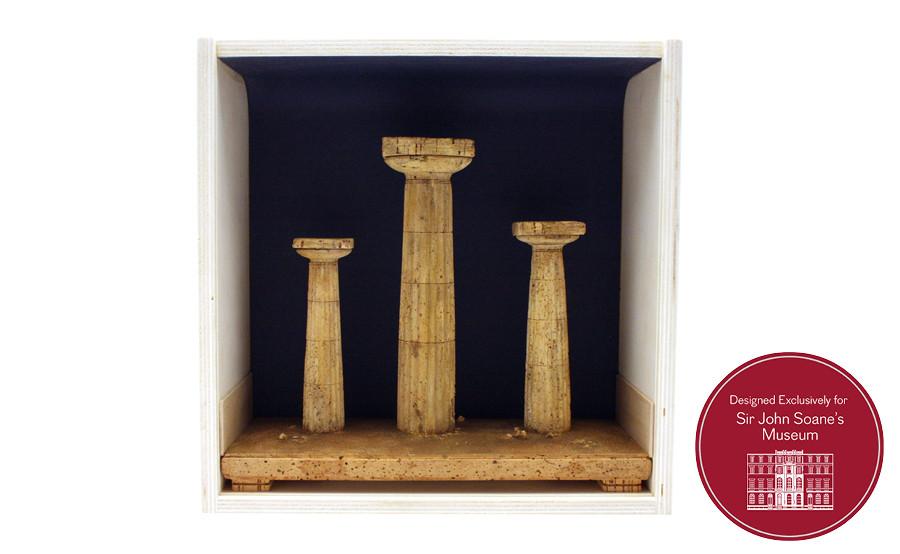

sjsm-cork-column2.jpg Kirstinimage/jpeg51.26 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg51.26 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg51.26 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg51.26 KB

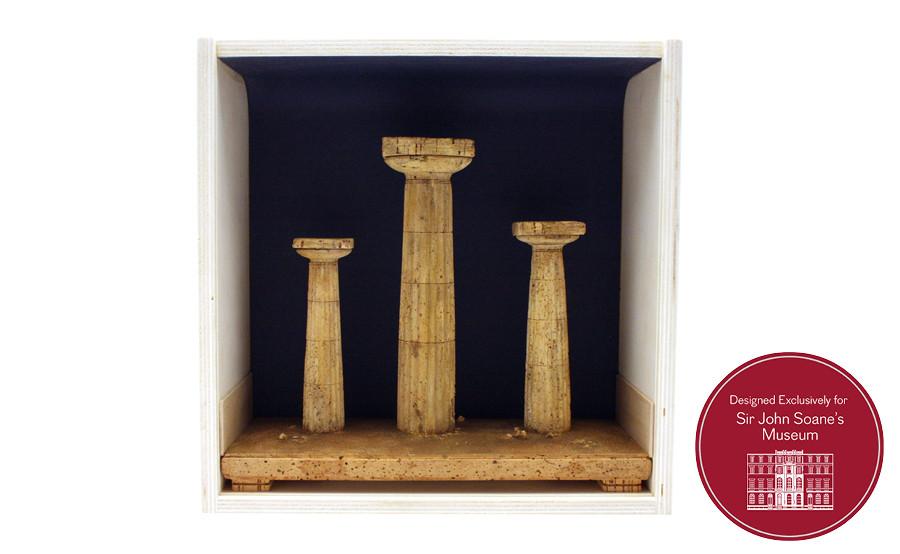

Deiter_Collen_Three_Columns_SJSM-2.jpg Kirstinimage/jpeg36.65 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg36.65 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg36.65 KB

Kirstinimage/jpeg36.65 KB

blueTest_0.png dp_adminimage/png67.12 KB

dp_adminimage/png67.12 KB

dp_adminimage/png67.12 KB

dp_adminimage/png67.12 KB

john-soane-museum-finalist.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg145.27 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg145.27 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg145.27 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg145.27 KB

john-soane-finalist.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg133.53 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg133.53 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg133.53 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg133.53 KB

soane-museum-2017.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg209.91 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg209.91 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg209.91 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg209.91 KB