Search results

Another collection Back to top

Nulla consequat eu tortor vel congue. Sed turpis ex, feugiat nec felis dictum, vestibulum commodo eros. Praesent lobortis laoreet tortor a fringilla. Sed metus leo, molestie nec facilisis id, facilisis et eros.

1. The Heir Back to top

In this scene, we meet our hero, Tom Rakewell. He has just inherited a fortune following the death of his miserly father, whose house is now yielding up its hoarded wealth.

Tom attempts to pay off a servant girl, Sarah Young – her gold ring revealing an earlier, now retracted, promise of marriage. Behind Tom, an inheritance lawyer steals gold coins, while an upholsterer attaching fabric to the walls finds a hiding place for money which tumbles out servants find hidden treasures in the fireplace and money behind wall hangings. A starved cat looks for food in a chest full of silver.

2. The Levée Back to top

In his new palatial town lodgings, Tom holds a morning reception in the manner of a fashionable gentleman.

Several visitors arrive to offer their services: a jockey, a dancing-master (with violin), a landscape gardener (holding a plan), a poet, a tailor, and a musician (seated at the harpsichord, believed to be Hogarth's great rival, Handel.

On the wall hang three new Italian paintings. We imagine Hogarth’s scorn here – he was known to dislike the fashion of acquiring Old Master works (which he called 'dark pictures') at the expense of paintings by British artists.

External guides Back to top

Due to the narrow Museum spaces and for the safety and comfort of our other visitors, we don’t permit external guides to lead their own tours in the Museum.

Working in Soane's Office Back to top

This section tells you about what it was like to work in Soane’s office, where the office was and how the pupils and assistants were expected to reach it. It also shows where Soane himself worked. There is a drawing made in Soane’s office to show all his built projects up to 1815. We see the kind of pen made from a goose feather which Soane and his pupils would have used.

Soane was one of the most successful architects of his time and parents would pay to send their sons – only men worked in his office – to be trained to be architects. They worked for 12 hours a day, later reduced to 11. In the summer it would be hot and in the winter dark and cold. They had to use a door at the back of the property so they didn’t walk through the house, and they weren’t allowed to mix with the domestic servants. A few of them didn’t prove good enough and didn’t work there for long. When they started, Soane would see how good they were at drawing by getting them to draw the rooms in the Museum. They would be with him for five or six years, learning to draw and design buildings and all the business which was related to architecture.

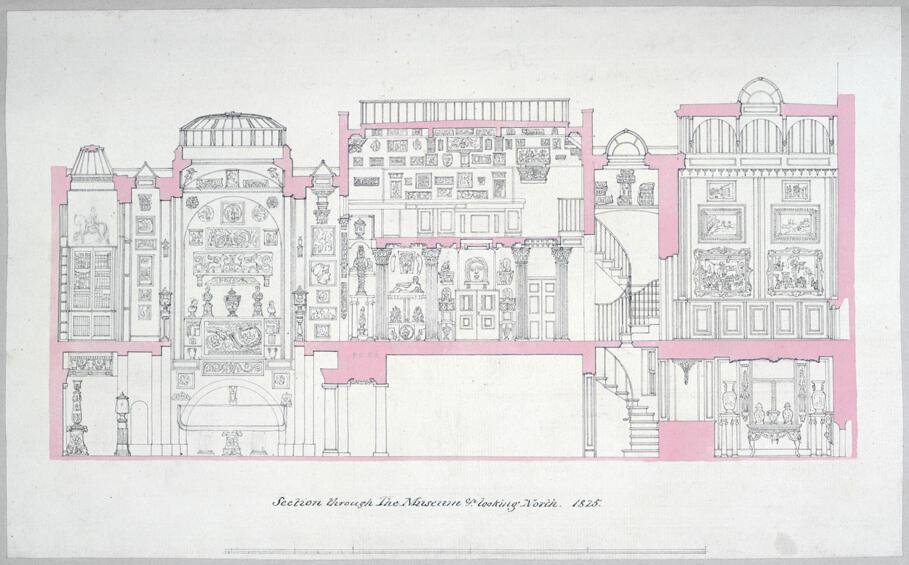

The Upper Drawing Office

The Upper Drawing Office Vol. 82/33

This drawing, made in 1825, shows a section through the back part of the Museum where Soane’s pupils worked. The areas left white show the Upper Drawing Office, and the office door they used (see also The Little Study). The Office is supported on columns above the area known as the Colonnade which connects the Dome, where you can look down to the sarcophagus, with the Museum Corridor from where the staircase leads to the Office. Light came down in the Office from two skylights above the benches and the walls were hung with plaster casts to instruct and inspire the pupils.

The Little Study

The Little Study P86 (detail)

This little room was where Soane would sit and work at the surprisingly small table which pulled out from under the desk as you can see. Here he would produce the kind of drawings which would be worked up by the pupils (like Original Sketch Design: Tyringham Gateway). He would also be able to keep an eye on who was coming and going in the back part of the house. In front of the window are blinds like modern Venetian ones but vertical so that Soane would adjust the light to have it just how he wanted it. Between the Little Study and the area below the Upper Drawing Office is the Dressing Room where he would tidy himself up and put on his wig and coat before meeting builders who, like the pupils, would use the office door at the back of the house. This is a detail from a drawing of 1822.

Public and Private Buildings

Public and Private Buildings P87

Here is a drawing showing all Soane’s buildings built between 1808 and 1815, drawn by Joseph Michael Gandy – Soane’s best draughtsman – in 1820. Look at how cleverly all the buildings are shown as if they are in a huge room. Some are shown as big models and some as pictures within the picture. Imagine how much work went into drawing them all, let alone designing them.

Quill Pen

Quill pen

In Soane’s time, some pens were made from feathers, also called quills. The best quills come from geese; the feathers used are those from the leading edge of the wings. They were sometimes dried and hardened in hot sand and they were shaped with a sharp knife – a pen knife – to form a nib. This could be fine or broad as required.

Metal pens were also starting to be used in Soane’s time and would be used for finer work. Soane’s Tyringham Gateway sketch was probably made with a quill pen like this one.

South Exhibition Gallery Back to top

Click the images for further information

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

View of the South Exhibition Gallery

Photo by Gareth Gardner

Adjoining Rooms

Adjoining Rooms 1989

Wood, glass, acrylic sheet, AC lacquer

Installation: 78 x 426 x 62 cm; three items: 78 x 142 x 62 cm (each)

Tate, London

Like the chair sculptures Conversation Seat (1986), Interlocking Chairs (1995) and Burnt Interlocking Chairs (1997), this work shows us how discrete components, in this case individual vitrines, combine into one work. It also expresses a Soanean mode of creating space: Soane did not create discrete rooms, but rather created a series of interlocking spaces, as in the Library-Dining Room and the Dome-Colonnade.

Marseille, Cité Radieuse

Photo by Gareth Gardner

Marseille, Cité Radieuse 2001

Wood, aluminium, glass, lacquer

102 x 200 x 10 cm

Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton

This work depicts the Unite d’habitation, a modernist residential housing principle developed by the architect Le Corbusier. He built these throughout Europe, the most famous of which is in Marseille.

Council of Europe

Photo: Prudence Cummings Associates

Council of Europe 1989

Wood, glass, paint, AC lacquer

60 x 60 x 15 cm

The artists

This work, which depicts the Council of Europe, is part of a larger series of works that explores the common European political and cultural heritage. Other sculptures include the European Court of Human Rights, the UN Security Council, and the European Parliament. It was made at the moment when the European Economic Community was turning into the European Union.

Apple, Sunny Vale

Photo by Gareth Gardner

Apple, Sunnyvale 2018

MDF, paper, card, paint, acrylic

91 x 91 x 7.5 cm

The artists

This work depicts the Apple campus in Sunnyvale, California, located in Silicon Valley.

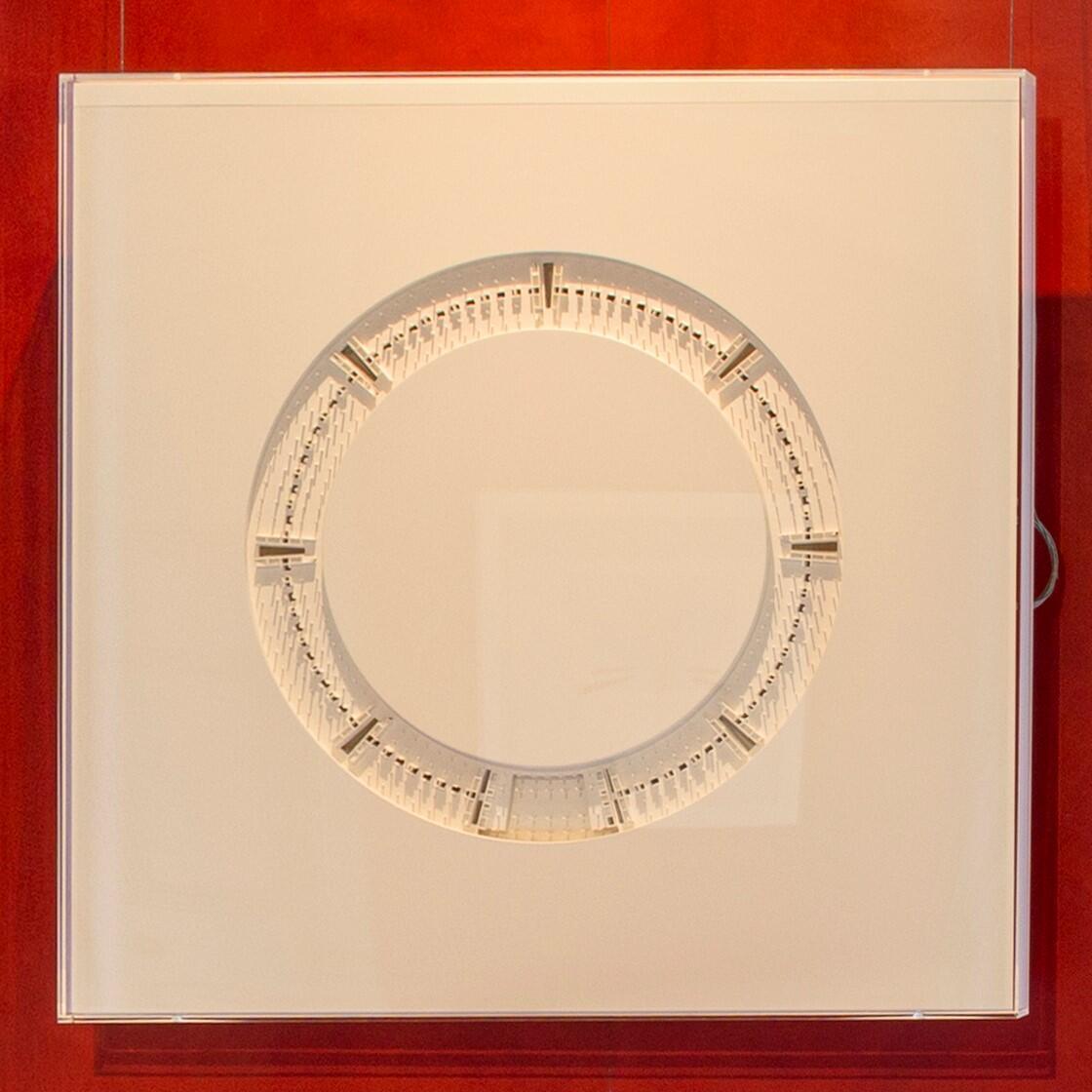

Apple, Cupertino

Photo by Gareth Gardner

Apple, Cupertino 2018

MDF, paper, card, paint, acrylic

91 x 91 x 7.5 cm

The artists

This work depicts the corporate headquarters of Apple, also called Apple Park, which was completed by Norman Foster in 2017. Both Apple works show how tech companies are the new patrons of architecture.

Apple Oblique (green)

Apple Oblique (green) 2015

Archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 310 gsm

75 x 75 cm

Cristea Roberts Gallery, London

This print depicts the Cupertino headquarters of Apple.

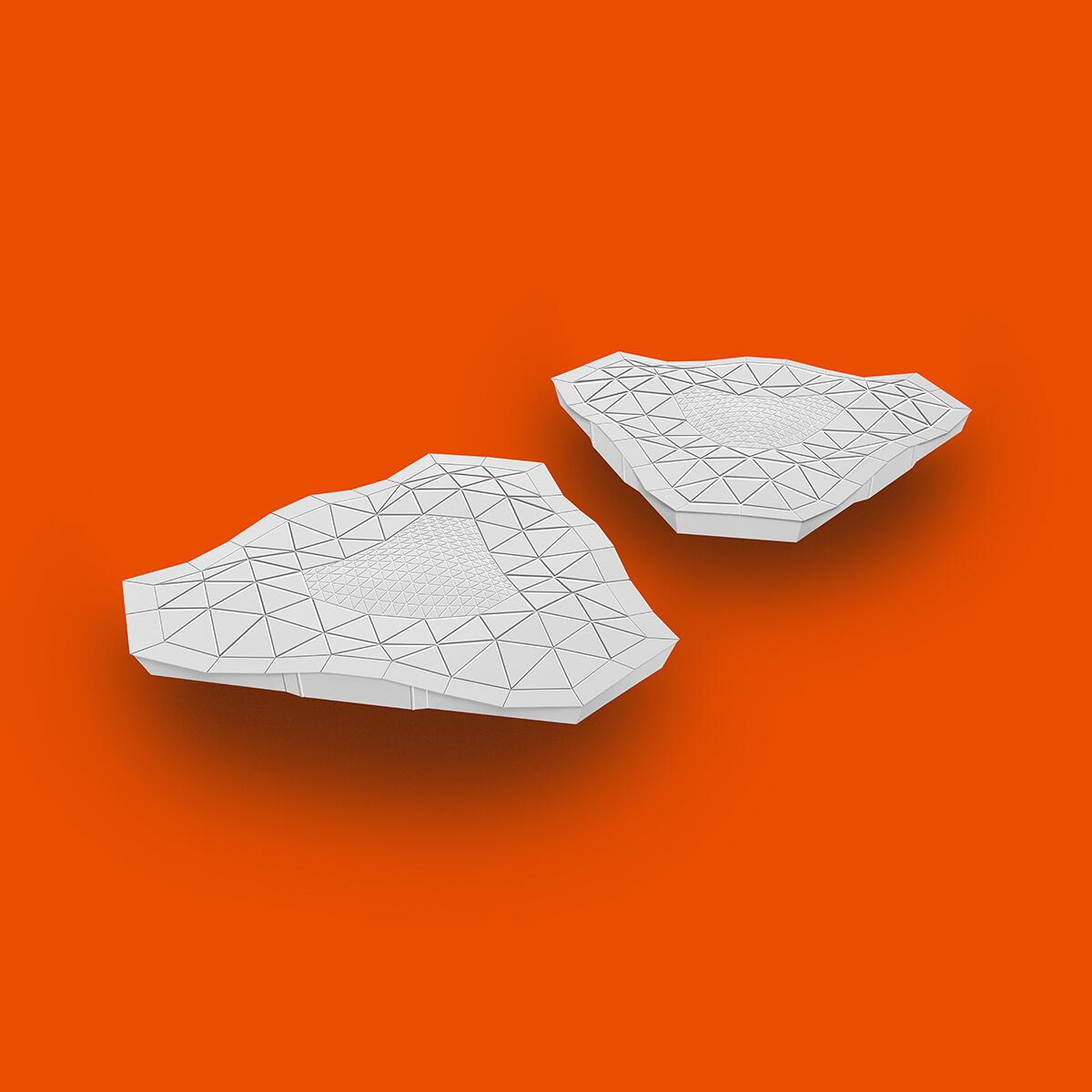

Nvidia, Santa Clara (orange)

Nvidia, Santa Clara (orange) 2015

Archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag 310 gsm

75 x 75 cm

Cristea Roberts Gallery, London

This print depicts the corporate headquarters of Nvidia, a technology company that designs graphics processing units for the gaming and professional markets. Since 2014 they have also focused on artificial intelligence.

Logo Works (x4)

Photo by Gareth Gardner

Logo Works (x4) 1998–99

4 screen prints on Somerset Satin 300 gsm

70 x 70 cm (each)

Cristea Roberts Gallery, London

These works depict banks and corporate headquarters towers, such as Deutsche Bank, BMW, IBM, Unilever. Each tower dominates the landscape in its city, playing a key role in each company’s public image strategy and functioning like a super logo that communicates a company’s identity.

Types of Drawings Back to top

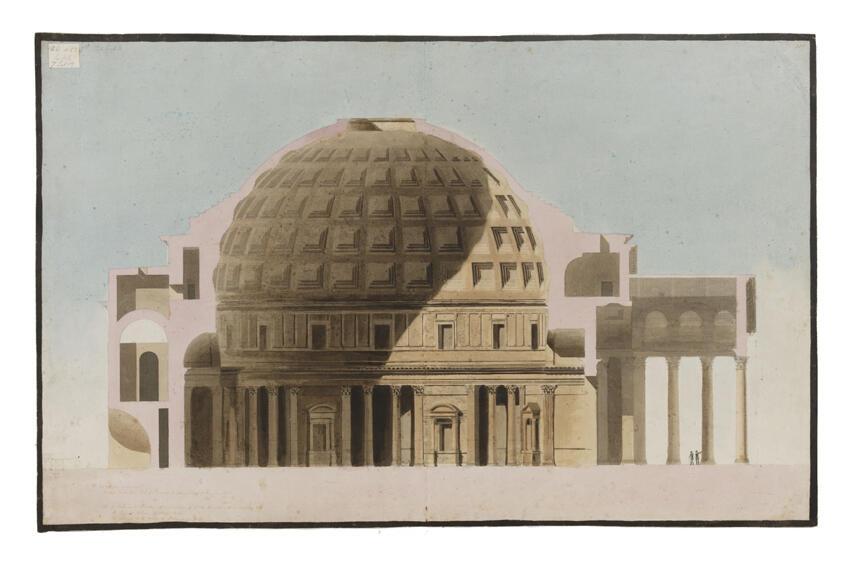

This section shows the different types of architectural drawings there are and what they are for. It shows the main four kinds of drawings: elevation, plan, section and perspective; together with more specialised kinds of drawings: bird’s-eye view and floor plan with laid-out wall elevations.

Some important buildings are shown: the Pantheon in Rome, one of the greatest Roman buildings to survive; Soane’s own country house, Pitzhanger Manor in Ealing and Lady Williams Wynne’s room, St James’s Square, designed by Robert Adam, whose drawings Soane bought for his collection.

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

Elevation: The Pantheon

Elevation: The Pantheon 45/3/54

There are basically four kinds of drawings which can be made to show buildings. An elevation like this one of the Pantheon in Rome (the best preserved ancient Roman building in the world, built in the early 2nd century AD) shows the outside of the building as if you were looking straight at it: this one is of the front of the Pantheon showing the shape of the dome over the huge central space and the porch, called a portico, supported on columns.

Plan: The Pantheon

Plan: The Pantheon 45/3/52

A plan, like this one of the Pantheon, shows the layout of the building seen from above as if the building were only built to just above ground level. You can see the huge round space in the centre of the building and the arrangement of the columns of the portico.

Section: The Pantheon

Section: The Pantheon 45/3/53

This is a section of the Pantheon which shows a slice through the building as if it were a cake cut in half. It shows the height of spaces inside the building and how they are arranged. Note how carefully the shadows are drawn to give a real feeling of how the dome curves. The walls which have been cut through are coloured in pink – a colour which was often used in this way by architects. These drawings of the Pantheon were made in Rome in 1778 when Soane was a student.

Perspective: Pitzhanger Manor

Perspective: Pitzhanger Manor Vol. 90/5

This is a perspective of Soane’s own country house, Pitzhanger Manor in Ealing, built from 1800 onwards. It shows how the building would look if you were really standing in front of it. Perspectives are probably the most difficult to draw as you have to work out the way the building will appear before it is actually built – but there are ways to do this using the plans, elevations and sections.

This is the original drawing for plate V in Soane’s book Plans, Elevations and Perspective Views of Pitzhanger Manor-House. There are other sorts of drawings, elevations, plans and sections in the book as well.

Bird’s-Eye View: Pitzhanger Manor

Perspective: Pitzhanger Manor Vol. 90/5

A bird’s-eye view is a very clever kind of drawing, which shows a building as it would look from the air, as a bird flying over the building would see it – hence the name. This drawing is also of Pitzhanger Manor and shows the arch over the entrance from the road, the gardens and an artificial ruin Soane built to the right of the house.

He would pretend that these were real Roman ruins and even made drawings showing how they would have looked when complete.

The whole thing was probably a sort of joke he liked to play on his visitors and friends. Unfortunately, although the house is still there, the ruins were removed after Soane sold the property. In Soane’s time artificial ruins like this one were built in gardens to remind people of those they had seen in Italy.

Floor Plan with Laid-Out Wall Elevations: Lady Williams Wynne’s Room, St James’s Square

Floor Plan with Laid-Out Wall Elevations: Lady Williams Wynne’s Room, St James’s Square Adam Vol. 40/70

Another kind of drawing is the floor plan with laid-out wall elevations. It is a combination of a plan for a single room with the internal elevations of the walls shown, as if it were a box with the walls flattened open. Sometimes the ceiling would also be shown on this kind of drawing.

This sort of drawing is easy for the client to understand and cheaper than a model. This is a drawing by Robert Adam’s office for Lady Williams Wynne’s room in a house in St James’s Square in London, and was drawn in about 1772. Robert Adam was a famous architect who had a big office in London, and was older than Soane. After the Adam office closed, Soane bought many of the Adam drawings to add to his collection.

title Back to top

On Earth, our view of the illuminated part of the Moon changes each night, depending on where the Moon is in its orbit, or path, around Earth. When we have a full view of the completely illuminated side of the Moon, that phase is known as a full moon.

On Earth, our view of the illuminated part of the Moon changes each night, depending on where the Moon is in its orbit, or path, around Earth. When we have a full view of the completely illuminated side of the Moon, that phase is known as a full moon.

On Earth, our view of the illuminated part of the Moon changes each night, depending on where the Moon is in its orbit, or path, around Earth. When we have a full view of the completely illuminated side of the Moon, that phase is known as a full moon.

Flaxman at the Saone pdf

South Drawing Room Back to top

Photos by Gareth Gardner

Conversation Seat 1986*

Wood, glass, lacquer

70 x 110 x 50 cm

The artists

*Artists’ copy of the original which is in the collection of the Norwegian National Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo

North Drawing Room Back to top

Photos by Gareth Gardner

Interlocking Chairs 1995

Wood, glass, lacquer

92 x 92 x 64 cm

Private collection, London