Search results

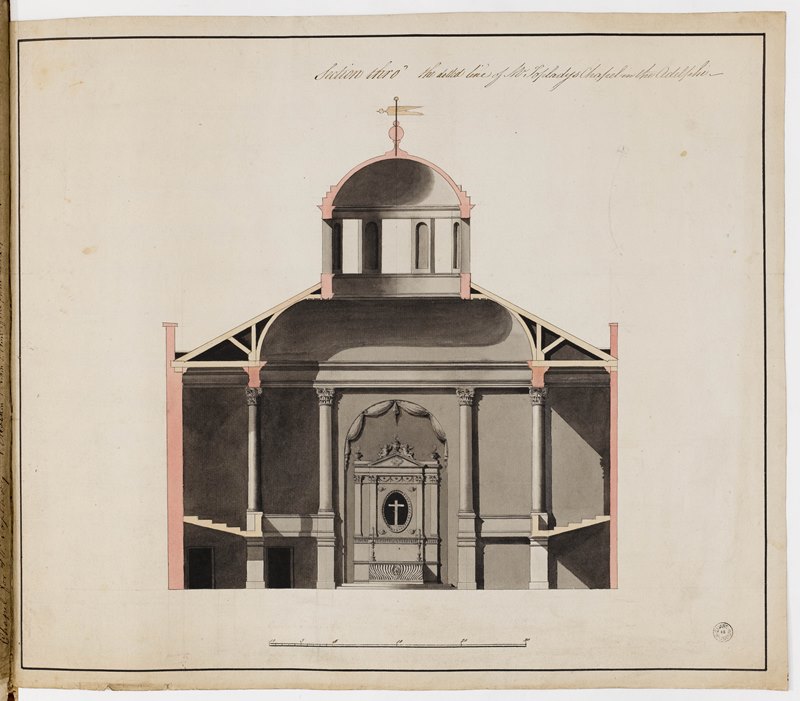

adelphi-robert-adam-augustus-topladys-chapel.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg90.93 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg90.93 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg90.93 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg90.93 KB

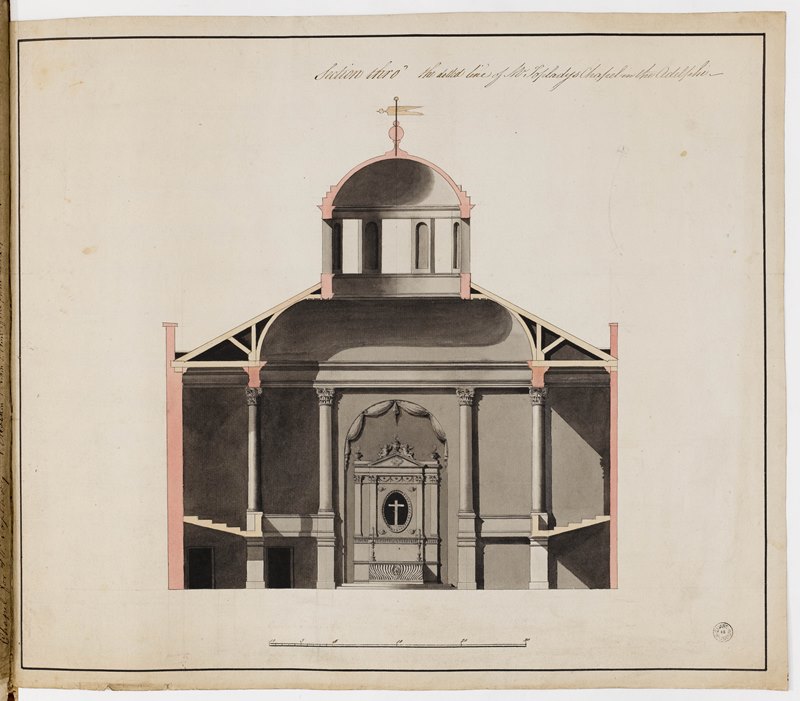

adelphi-adam-ceiling-garrick-victoria-and-albert.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg97.26 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg97.26 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg97.26 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg97.26 KB

imagefield_gdk1ZO.jpeg dp_adminimage/jpeg4 KB

dp_adminimage/jpeg4 KB

dp_adminimage/jpeg4 KB

dp_adminimage/jpeg4 KB

miniture-georgian-houses.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg163.49 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg163.49 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg163.49 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg163.49 KB

soane-parametricism.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg78.19 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg78.19 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg78.19 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg78.19 KB

soane-museum-parametricism.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg23.19 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg23.19 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg23.19 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg23.19 KB

soane-museum-high-tech.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg64.71 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg64.71 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg64.71 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg64.71 KB

soane-high-tech.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg21.64 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg21.64 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg21.64 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg21.64 KB

metabolism-soane-museum.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg82.8 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg82.8 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg82.8 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg82.8 KB

soane-museum-metabolism.jpg mblowfieldimage/jpeg24.71 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg24.71 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg24.71 KB

mblowfieldimage/jpeg24.71 KB