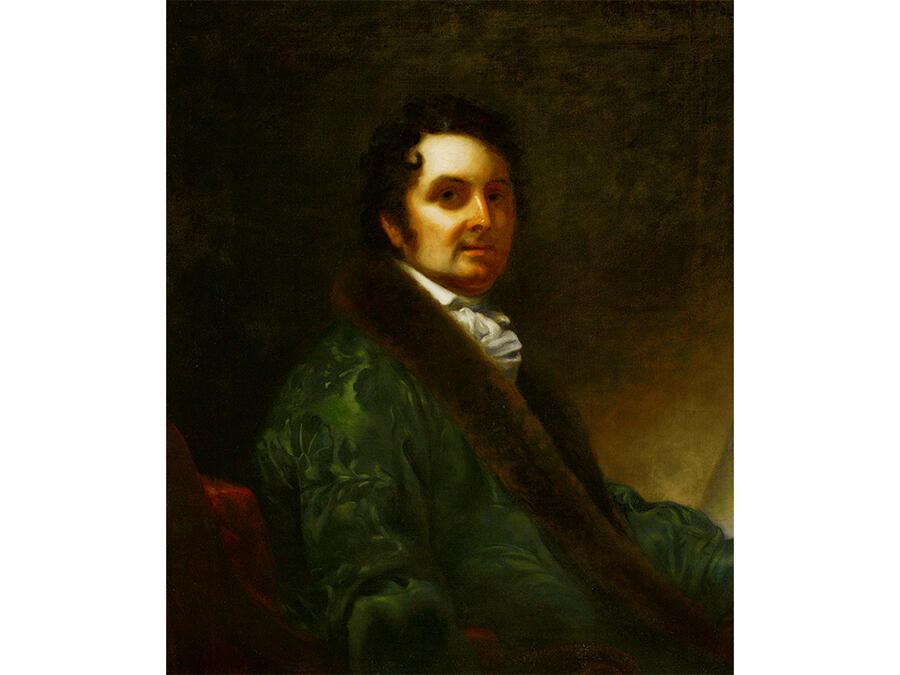

Fig.3. Portrait of Joseph Michael Gandy by Henry William Pickersgill, c.1822. SM XP52

After his return to London, apart from his regular commissions from Soane, Gandy was chiefly employed as a topographical draughtsman for John Britton and his series of Architectural Antiquities and travelled widely around the country. Clearly Soane and Gandy discussed what he saw on his travels and in one letter written to Soane in 1816 when he was staying in Harrogate to try and get over Eliza’s premature death the previous November Gandy gave him extensive advice on the places and buildings he might visit in the north (Fig 3).

Sadly there is very little record of the artistic interactions between Soane and Gandy and of the discussions they must have had about the compositions Soane commissioned. There are just one or two letters in which Gandy discusses certain pictures and his methodology. It is clear, however, from his surviving topographical sketchbooks just how interested Gandy was in in natural phenomena, and particularly those pertaining to the weather and to light and this will certainly have resonated with Soane with his great interest in hidden light sources and lumière mystérieuse. Gandy certainly also appreciated what Soane was trying to achieve in his house-museum: in a letter thanking him for a copy of his 1835 Description he began:

‘ Behold! Your munificent hand has honoured me with a splendid/ Book, an Epitome of your Dwelling Place, a Museum whose contents in detail/ require innumerable volumes to describe all the trains of thought they lead/ to, whose Library display all that art and science can make useful, whose/ antient and modern sculptures and paintings are exemplars of the lives of/ other congenial minds, writing in a halo encircling their Author. Who can/ tread those tapestried floors, pebbled and glass mazed pavements, knobbed/ and historic painted ceilings, enamelled windows and orielled recesses receiving/ dioptric light from unseen sources, illumining invaluable Gems, Cameos and/ seal rings, the number of revolving pictured and carved walls folding doorlike/ valve within valve grading from shade to light, the many semblances of/ departed worth recalling us to human life, leaves our minds oscillating between heaven and earth! Go Student and mark thy ways with equal effect, not like birds of passage who gayly skim the surface of the waters, and fathom not their depth.’

Gandy was never elected a full Royal Academician, despite several attempts between 1809 and 1820, and his last architectural commission was in 1825. In 1833 he left central London and relocated to Chiswick where at 58 Grove Park Terrace there is now a blue plaque recording the residence there of ‘Joseph Michael Gandy … Architectural Visionary’ between 1833 and 1838. As Brian Lukacher records in Joseph Gandy: An Architectural Visionary in Georgian England (Thames and Hudson 2006) ‘for the remainder of his life Gandy focused on scholarly pursuits by continuing his collection of drawings and archaeological research on English castles and by writing a voluminous manuscript of architectural history and theory. He also embarked on an unwieldy project of illustrating a world history of architecture.’

Sadly Gandy died on 25 December 1843 in Plympton House, a private asylum to which his family had committed him at some time between 1839 and 1841. It is not known where he is buried. His fame lives on in his numerous works in public and private collections, not least those which adorn the walls of Sir John Soane’s Museum.