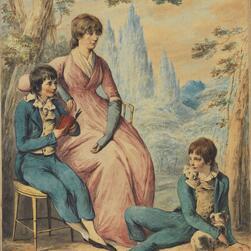

Soane’s wife Elizabeth or Eliza was born in 1762 in relatively humble circumstances – her father, Jonathan Smith, kept The Castle pub in Cowcross Street on the edge of Smithfield Market. Both her parents died when she was an infant and she became the ward of her uncle George Wyatt, a wealthy London builder who brought her up, and for whom, when she was older, she kept house.

It was through her uncle that in 1783 Eliza met the young architect, John Soane, who had established his architectural practice in London in 1780, after returning from two years in Italy making a Grand Tour. Soane had been trained in the office of the architect George Dance the Younger who knew George Wyatt well through their mutual City connections.

The couple married on 21 Aug 1784 at Christ Church, Blackfriars, living initially in Margaret Street in Marylebone.

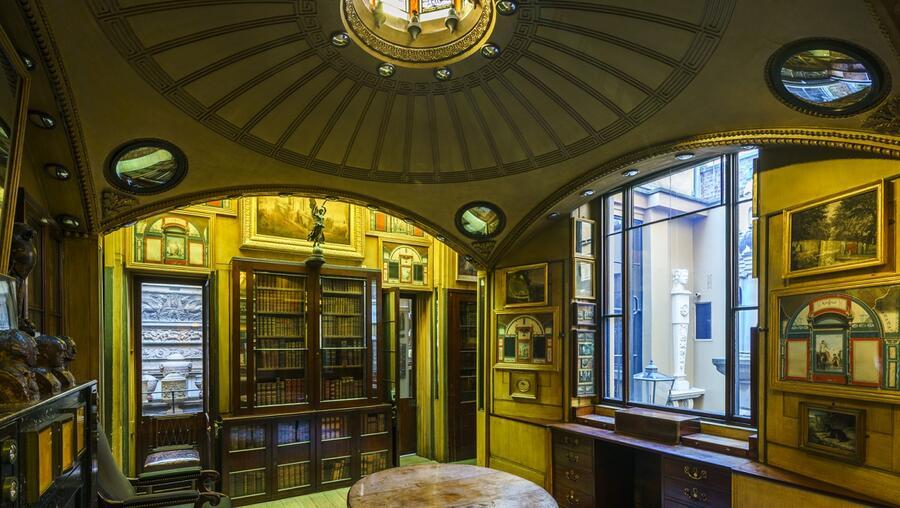

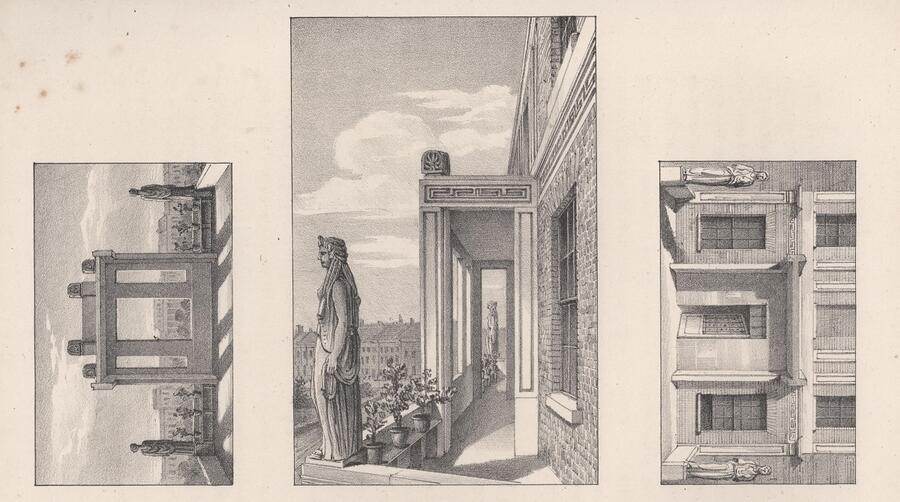

Six years later in 1790, George Wyatt died and left a large portion of his considerable fortune to John and Eliza, part of which Soane used to buy and rebuild No.12 Lincoln’s Inn Fields (next door), into which they moved in 1794 with their two sons John and George. Later on Soane bought and rebuilt this house, No.13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which they moved into in 1813, and which would later be left to the nation (along with numbers 12 and 14) as Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Here at one end of this dining table Eliza would have presided over the many dinners the couple hosted for friends over the years, which are recorded in their diaries.

The Dining Room is dominated by a portrait of John Soane painted by Thomas Lawrence in 1828, when Soane was 75. But there is also a hidden portrait of Eliza in this room. The ceiling paintings by Henry Howard were not added until 1834 and the head of ‘Night’ in ‘Night and the Pleiades’ [P4] (above the dining table) with its surrounding crepe veil, is thought to be a portrait of the late Mrs Soane and would originally have marked her customary seat at the table.

In the middle of the room on the right-hand side can also be seen a model of Eliza’s tomb [L78].