Search results

URBANA, 1995 - 2005 Back to top

URBANA, my first partnership and practice, was formed with Kashef Chowdhury in November, 1995. Our passion for architecture resulted in a deep friendship and belief in the craft, resulting in a decade-long partnership in both work and life. At that time, a leading Real Estate company in search of ‘wow-factor’ designs approached us to commission thirty of their high-end development projects. Looking back, I can only be proud of rejecting the temptation of the offer. Though the path after this was challenging, we sustained the passion of our practice through small yet meaningful commissions.

In 1997, one and a half years after our practice’s conception, we won a competition to design and build the Museum of Independence of Bangladesh in Dhaka. Hard won and much awaited, we nonetheless understood the immense responsibility associated with the opportunity. The project demanded an investigation into contemplation and timelessness. The liberation of Bangladesh is a tale of duality: independence gained through the selfless sacrifice of a brutal war. Freedom has a preferred direction: upwards. Anything aspirational assumes an upward gait. And yet, memory, loss and sadness urges for the subterranean: a desire to be buried and also, after a time, unearthed. We introduced a horizontal expanse parallel to the flatness of the park, a platform of celebration: and a vertical offering of hope, defined by the Tower of Light. The history of revolution, struggle and genocide was gently tucked below ground in the museum beneath the plaza. The project that began with positive vigour in 1998 finally found its completion, sixteen years later, in 2013.

Before this, our first completed project as URBANA was NEK 10, a family residence in Dhaka. A project with a modest budget, we explored the very basics of materials and responded to the tropical climate with large openings, terraces, verandahs and open green space. In the subtropical, humid climate of Bangladesh, architecture can essentially be a pavilion: a roof to provide shelter from the elements and a plinth to keep us above the monsoon rain are adequate to create a primal hut.

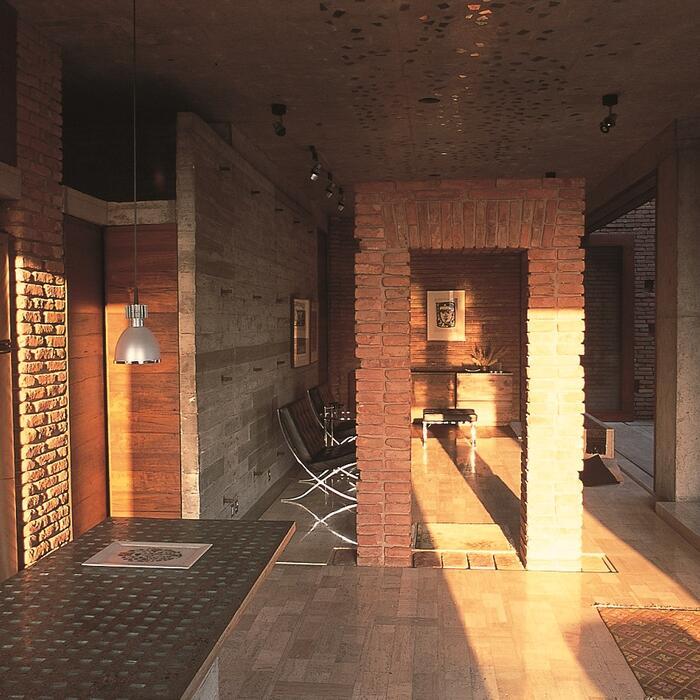

Another notable project, A5 Pavilion Apartment, was built as our own residence and cemented many of our explorations around climate appropriateness. Here we attempted to further blur the edges between inside and out. The large volume of the nature court combined with flexible shutters to create airflow, kept the spaces ventilated throughout the hot summer months. The project addressed the basic methodology of reduction, redefining 1,250 square feet of free-flowing space on the top floor of a contemporary urban apartment dwelling. The first step of planning was to strip the clients’ architectural requirements down to only the essential of human activities, in order to discard the complexities and extract the basic essence of living. This generated four major spaces: eating, sleeping, socialising and being with nature. This project sought out ways of repurposing discarded materials, hand-crafted to renew. A5, designed as an Architects’ Residence, was completed in 2001.

Ten years in URBANA helped to craft my confidence, so as to combat the inhibitions, intimidations and fears of being a woman in a man’s world. I spent long hours on site, at times staying up all night in the cold winter months and during trade shows to meet deadlines. It’s all in the attitude; knowing one’s craft and fostering connections with the people who give life to one’s drawings.

MTA, 2005 - Back to top

Unfortunately, the partnership which formed URBANA did not end in peace. I left the practice and gathered the self-assurance and vision to set out on my solo journey in the pursuit of architecture. Marina Tabassum Architects (MTA), a studio-based practice, was set up in June, 2005. I decided that my passion would be the driving force behind the endeavour, with a focus on combining research, teaching and practice to inform our output. I decided consciously to keep the office and staff size at optimum operational levels, in order to select projects carefully and limit their number each year.

A building must breathe without the help of artificial means. That is an obsession, I confess, that I pursue quite earnestly in all projects. Porosity of the building skin, open courts and long verandahs are ingenious traditions from the pre-air-conditioning-era that are still valid in contemporary times. Investigations into contemporising these techniques in order to reduce dependency on mechanical means resulted in several MTA projects that employ spatial planning and the addition of voids and stacks to allow cross ventilation.

Spirituality vs symbolism Back to top

In 2005, around the time MTA was founded, one evening my grandmother, Sufia Khatun, invited me for tea. She had with her a map of the land she owned in the north of Dhaka. She offered to donate some part of it to build a mosque. It was her wish that I design and build her dream project. Since my grandfather’s passing in 1971, she had lived a very modest life as a widow in a white saree: the sudden demise of my mother, her eldest child, in 2002 put her in a deep sense of loss. So too for me; this loss was perhaps the lowest and darkest point in my life to date. It was a moment in time when grandmother and granddaughter both sought healing and designing the mosque became our process. My grandmother passed away within a few months of the ground breaking at Bait ur Rouf Mosque in December 2006.

The promise to realise her dream turned into a six-year project where I was the architect, builder, fundraiser and client. Bait ur Rouf Mosque was the first commission of MTA and also the most revered around the world.

The initial idea was to search for the essence of Islam, devoid of ritualistic and symbolic attributes – to question, ‘What is a mosque?’. The first mosque of Islam was built under the directive of Prophet Mohammad. It was primarily a space for a congregation of followers. In addition to communal prayers, the mosque housed social, administrative and judicial events that helped establish and spread the doctrine of the religion. The genesis of the mosque form has its roots in the vernacular house tradition of Medina, elongated to hold the assembly of Friday prayers. Clarity of space, devoid of hierarchy, is tantamount. Instead of glorifying symbolic features such as domes or a minaret, it felt right to focus on the spirituality of the space that would heighten one’s sense of being in communion with God.

Light became the major element of design.

In Bengal, the glorious legacy of mosque architecture dates back to the thirteenth century with the advent of Islam confirming the age of the Sultanates. Built in brick, these mosques adapted to local building traditions. I took inspiration from these brick structures in order to re-establish the lost connection between the contemporary practice and the rich heritage of mosque architecture.

Dhaka is one of the densest and the fastest growing cities in the world, with some 20 million inhabitants. Due to the lack of decentralised planning policies, all roads in the country lead to Dhaka. The northern fringe of the city used to be farmland, which went through rapid transformation to become residential settlements over the last two decades. In anticipation of a dense, unregulated neighbourhood, the mosque offers order in chaos. The main prayer hall is designed as a place of refuge where everyone is welcomed; a pavilion on eight columns wrapped in a brick structure that houses the ancillary functions of the mosque. The punctuated brick walls and open courts help to keep the building ventilated throughout the summer months and create a truly porous building, open to external light, sound and climate.

The local community, who are the main mosque attendees, helped with the process of construction by funding the building in small amounts; this fostered a sense of communal ownership. The space, form and material remain in their elemental state – light being the only ornament that glorifies the atmosphere – and they respond to the six seasons of Bangladesh.

Process vs object Back to top

The building industry in Bangladesh relies upon unskilled physical labour. Very few people can read construction drawings. Quite often, architectural instructions and designs are communicated with sketches, samples or 3D renderings, alongside vigilance onsite to avoid major errors in construction. This has allowed me and my colleagues to develop some long-standing relationships with highly skilled artisans; thus we learnt to appreciate the beauty of imperfections of hand crafting.

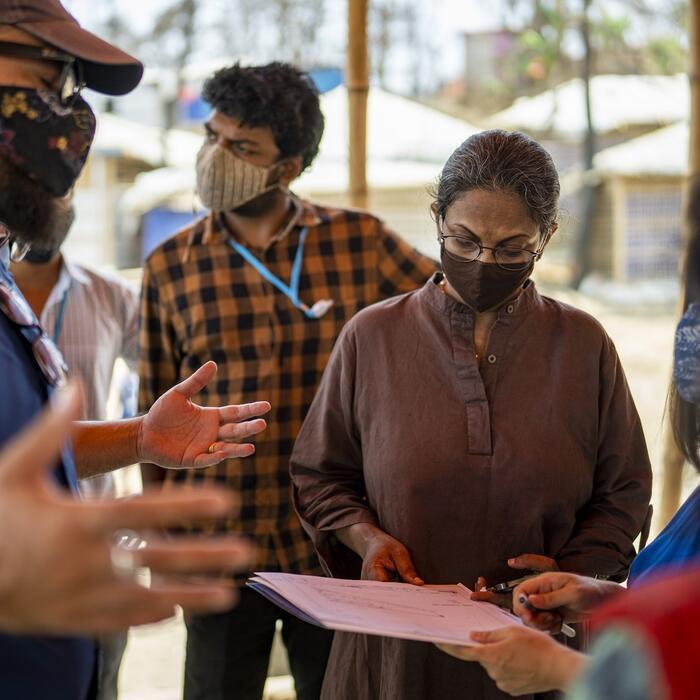

90% of Bangladeshis have little to no familiarity with architects or architecture as a profession. Quite often, participatory processes are required in order to be inclusive and to develop a sense of ownership in projects for the community.

Our projects in the Rohingya Refugee Camps in Ukhiya focus on building resilience of people and nature through co-creation. The natural forest in Teknaf was ruptured by the influx of one million refugees from Myanmar in 2017; this high density population and lack of vegetation subsequently resulted in rising temperatures in summer and landslides during the monsoon season. Our project includes participatory workshops and engagement within these refugee communities to facilitate regeneration of the forest through various methods of planting, including seed bomb and bamboo nailing techniques. The activities are not only therapeutic but also enable participants with the knowledge of and motivation to care for the environment.

In Louis Kahn’s words, ‘…architecture has no presence .… Only a work of architecture has presence, and a work of architecture is presented as an offering to architecture. Architecture has no favourites;…it has no preference for technology. It just sits there waiting for a work to indicate again to revive the spirit of architecture by its nature, from which people can live for many years.’

It is immensely liberating to realise that an architect is not bound by the four walls of a building but instead can engage in broadening the agenda of architecture. One can transcend visual dominance and object-making towards an architecture of relevance, in response to time’s needs.

Dwelling in the delta Back to top

The Panigram Resort in Jessore is 150km to the north of the Sundarbans (the largest mangrove forest in the world and home to the Royal Bengal Tigers) and to the south of the Padma river. The southern part of the Padma river was created by pro-gradation of the Ganges estuary by accumulation of silt. This highly fertile land of the matured delta is predominantly agrarian.

My first visit to the site in 2013 revealed the innate beauty of living symbiotically with nature. The thought of invading this primal quietness of life with the roaring noise of architecture felt like a crime. Ironically, the villagers, especially the younger generation, are drawn to the glitz of city life. For them, the city holds all the answers to their troubled aspirations for a ‘better life’. As news of our project travelled through the village, the community expected (and were excited by) the new ‘Dhaka’ that was to be born in the remote village of Taherpur. Instead, we visited houses and enquired about the recipe for building with mud. We praised the women who maintained their mud houses so beautifully, as if they were pieces of art. The village elders – those whose knowledge had become obsolete – were suddenly once again a rich encyclopaedia of information, a reference for our conversations.

A courtyard ‘uthan’ – the lived space – is the soul of a Bengali household. Undefined by any physical boundary, an ensemble of the elements of daily life are casually placed to give a sense of enclosure. Earth as its floor and sky as ceiling, the room repeats from one court to another, creating a social atmosphere – every household is unique, yet with a deep sense of communal connectivity. It is a theatrical display of life lived with nature. From dawn to dusk, the space changes character as the users move through their daily rituals of livelihood. MTA’s installation at the 2018 Venice Biennale, ‘Wisdom of the Land’, presented a courtyard of a Bengali hut as a response to the curators’ theme of ‘Freespace’. The structures we presented in the Arsenale built upon these traditional techniques of space-making, as well as our research within them, producing an ever-changing, adaptable architecture that went beyond the visual choreographing of daily life.

The Panigram project offered an opportunity to bring back the lost pride and belief in the wisdom of the land crafted over hundreds of years of dwelling in the delta. We believe that contemporary creative theory and practice must actively engage in reconnecting with the values of living meaningfully and symbiotically as a natural being. We opted for a minimally intrusive approach by including the villagers in the construction process and incorporating local knowledge of vernacular tradition. Through our engagement, we realised that keeping the Panigram villagers in their original locations would require provision of empowering opportunities, to revive the pride of craft, place and belonging. A cooperative named Panigram Community Initiatives was established to generate various activities and workshops to empower villagers to develop skills that would eventually lead to economic prosperity.

Another of the Panigram Resort’s community initiatives is the $2,000 Homes project, a co-creation model and education programme, initiated by MTA in collaboration with the community architects group, POCAA, to enable villagers near to the Panigram Resort to build their own houses. The process began by encouraging villagers to save, contributing small amounts to a seed fund (the collective savings of the villagers and one-time donation by Panigram Community Initiatives).

Members of the savings group can apply, each in turn, for a loan of up to $2,000 in order to finance the building materials for a modular house to improve their own living conditions. This is a budget for a building with two bedrooms and one bathroom. As architects, we listened to peoples’ aspirations: they design their dream houses as they have done for generations; and we provide our technical knowledge of and insight into space making. The process involves mutual respect and sharing. It is minimally intrusive to maximise the impact of architecture. This and Panigram Resort’s commitment to socially and environmentally responsible co-existence, in the context of Bangladesh’s Delta, sparked several subsequent programmes, bringing craft, food, agriculture, health-hygiene and education into focus.

Impermanence Back to top

The brick building tradition has strong roots in the Ganges delta. Architecture of power – be it political, cultural or religious – used brick when it sought permanence. The Buddhist monasteries dating from the third century BC were built with baked bricks; the Hindu temples showcase the finest terracotta depictions of the mythologies of Ramayana and Mahabharata.

In contrast, the architecture of human dwellings, those which frequently adapt to change and evolve, employ organic, impermanent and locally sourced materials.

Impermanence is embedded into the dynamic nature of the Ganges delta. The interplay of erosion and emergence is a unique phenomenon that has shaped the lives of Bengalis dwelling in this fragile land at the confluence of three major rivers, the Padma, Meghna and Jamuna. There exists a duality of joy and untold torment each year for a large number of people living along the banks of the streams of Bangladesh. The water level rises during the monsoon season (from June to October). The tributary streams carry excess water from the Himalayas, which causes the rivers to inflate and expand their territory, causing the banks to erode and readjust.

Along the Ganges-Bramhaputra basin, houses are adapted to a flat-pack system with a wooden frame and corrugated metal sheets. In the wake of river bank erosion, the locals disassemble their houses and move to safer locations. Houses move, the villages move along with the bazaars. In some cases, entire towns have shifted location. Some families have moved three or four times, while some have lost their means to start anew and moved to the city slums in search of their livelihoods. We attempted to showcase some of these stories – of complex existence and unending negotiation between human and nature – as part of our presentation at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial in 2019. In ‘Inheriting Wetness’, MTA’s investigation into landownership and precarious inheritance laws offered a closer look into the human lives affected by transient geoformations, accelerated by the effects of sea level rise. We bought three flatpack houses from a local market in Dohar and shipped them to the venue. On average, each house cost £1,500 and took three architects and a carpenter to put together in some fifteen days on site.

The Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers both combine to form one of the three largest river sources of water and sediment for the oceans. The tidal dynamics of low currents in the dry season forms sedimentation, locally known as char. For the landless (those with drastically low incomes), chars offer some years of relief as they settle with their families, fishing and cultivating the land. A shack made from tall grass costs nothing but provides a roof over one’s head. Chars are not land. They belong to the river. The transitory nature of these tread-able parts of the river does not allow long term planning. One must be ready with an exit plan in case the river overruns the char.

‘A place does not merely exist…it has to be invented in one’s imagination.’

The Bay of Bengal is a hotspot of climate insecurity, its ecosystem already affected with accelerated sea level rise. The irony is that the people in the coastal areas who are being affected by climate change have zero carbon footprint. These coastal communities rationalise the harsh reality as God’s will and keep adapting to the changing circumstances. We architects, as a profession, have a responsibility toward them. Part of that responsibility is about bringing change to a building and construction industry that contributes to 50% of climate change.

Architectural pedagogy needs to bring climate crisis to the forefront of education.

In 2020, our MTA office work slowed down during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. We dedicated the lull to exploring the idea of a flat-pack modular house for the landless char dwellers. This exploration resulted in Khudi Bari, a lightweight modular spaceframe structure with bamboo and steel joints, easy to assemble and disassemble. A three-metre module of Khudi Bari costs £300 and can house a family of four. To date, we have housed four families in Char Hijla, in order to understand the natural responses of local people. We are in the process of housing one hundred families by June 2023. Architects of the twenty-first century must address the imbalance in our environment created by extraction, over production and exploitation of resources that has put our existence in crisis. Architecture can transform our stock pile of waste into potential building materials with collaborative research.

Architecture can reinstall pride in the age old wisdom of living symbiotically with nature. Architecture can empower communities to secure better lives and living conditions. And I firmly believe all this can be achieved without sacrificing the innate objective of space and place-making. Every site has a story.

Architecture adds to the narrative by building upon the ingredients sought out from these stories. Therefore, before we ask the brick what it wants to be, the conversation must begin with the question: ‘Who are you, brick? What is your story?’

Watch the lecture Back to top

Suweda Back to top

Bait Ur Rouf Mosque, Dhaka.

Image Credits: Sandro Di Carlo Darsa and Hasan Saifuddin Chandan

"In this image of Bait Ur Rouf Mosque, I find that Marina Tabassum is attempting to heighten one's sense of spirituality through the light from the crisp-cut ring of the roof, and the red-brick walls that run-up to the broad sky. Her use of light and space in this Mosque is not only aesthetically-pleasing, but also thought-provoking to allow people to form a stronger, and deeper connection to God."

Liam Back to top

Inheriting Wetness, Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2019, Sharjah, UAE

Image credit: Sharjah Triennial 2019

"For me, Inheriting Wetness calls into question the nature of ‘land’ as a hereditary concept; in such a dynamic landscape, Marina Tabassum highlights the hardship of families having no fixed abode and captures how the people of Bangladesh think about ‘home’."

Molly Back to top

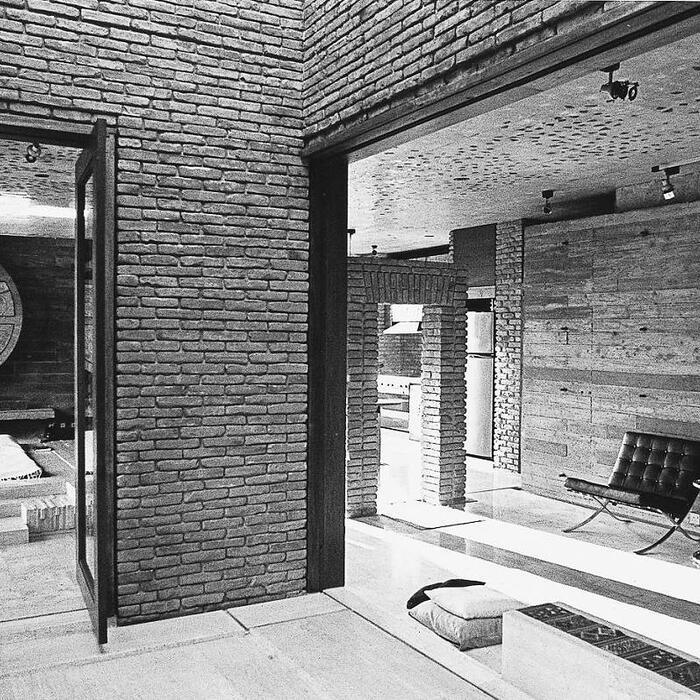

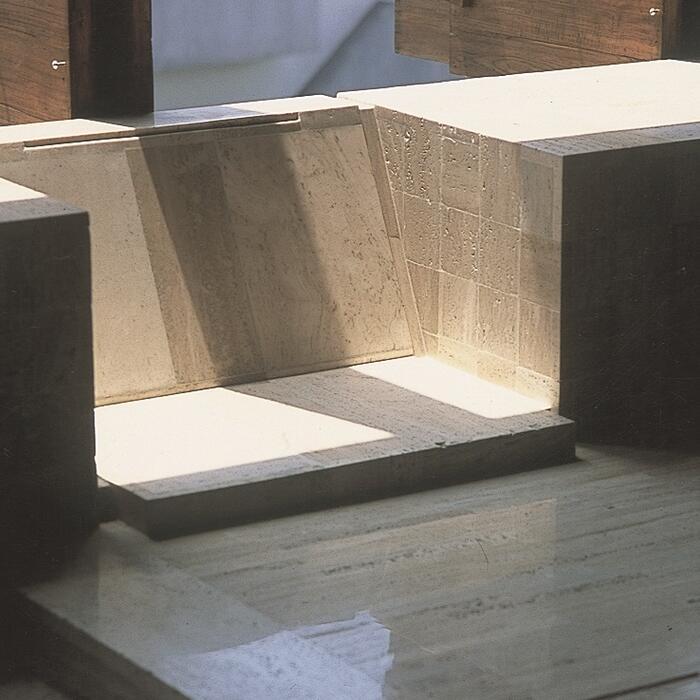

A5 Pavilion Apartment, Marina Tabassum and Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury, 1999 - 2001.

Image credit: MTA

"I chose this work because of the beautiful synergy of the clean blocks of light and the clean lines of the stone. Such simple colours and shapes come alive with the addition of sunlight to create numerous places to look and patterns to see. Such clean geometry also works really beautifully with the stark contrast between light and dark, the chiaroscuro lending a timelessness to the image that goes hand in hand with the Classical images in Sir John’s own collection. This piece also really showcases John Soane’s love of light as a natural architectural feature and reflects Marina’s collaboration with the natural world to form the idea of a building as a natural being."

More about the Youth Panel

The Youth Panel is a group of young people aged 15–24 who help the Museum shape the activities, events and opportunities we offer young people. Meeting roughly once a fortnight, joining the Youth Panel provides a great opportunity to develop real skills that will be invaluable in a future career, whilst also meeting other young people, having fun and developing new skills and interests. Find out more.