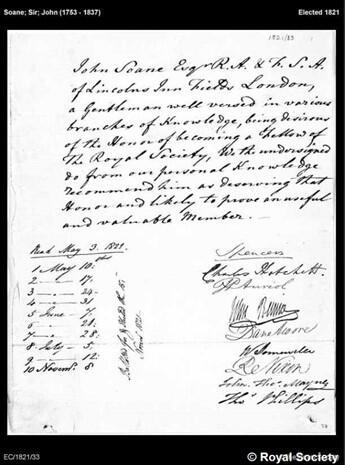

“John Soane Esqr RA & FSA of Lincolns Inn Fields London, a Gentleman well versed in various branches of Knowledge, being desirous of the Honor of becoming a Fellow of The Royal Society, We the undersigned do from our personal Knowledge recommend him as deserving that Honor and likely to prove an useful and valuable Member."

Fig. 1. Sir John Soane's election certificate to the Royal Society, 1821.

Soane registered his scientific interest as ‘antiquarianism’. There is little record of his contribution in terms of papers to the Society’s long-standing publication, The Proceedings of the Royal Society. Nevertheless, it is clear that he valued his Society fellowship highly, for F.R.S. is included on his tomb inscription in St Pancras Gardens. He also set up the 1833 Act to bequeath his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and its contents with a Fellow of the Royal Society as an obligatory, or Representative, member of the Board of Trustees.

Accordingly, at Sir John Soane’s death in 1837, (he was knighted in 1831), the first representative Royal Society Trustee on the Board was Alexander Douglas, the Duke of Hamilton, a Whig MP who had a stated interest in Egyptology. In fact, his dedication to the subject was such that he stipulated in his will that when he died he should be embalmed and buried in a sarcophagus (a request duly carried out). As a further connection, he was Grand Master of the Freemasons of Scotland at the time of Soane’s election and, as a Trustee of the British Museum, he seems to have been well equipped to shepherd Soane’s gift to the nation through its early years.

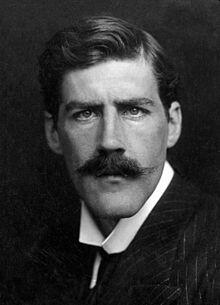

The Duke of Hamilton was succeeded in 1852 by Philip Grey Egerton (Fig.2), again an individual with aristocratic roots, but who had been elected a Fellow in 1831 for his ‘various acquirements in Natural History and particularly in Geology’.