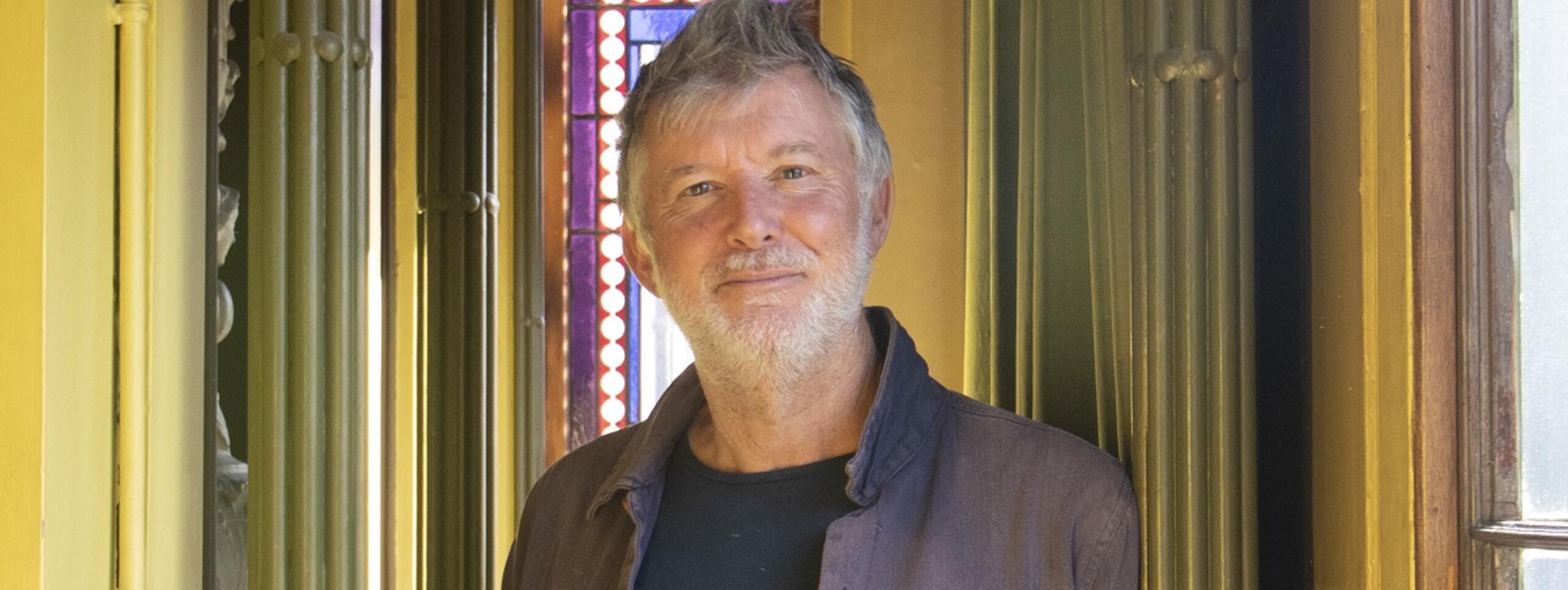

Each year, the Soane Medal is awarded to a practitioner, historian, educator or writer who has made a lasting contribution to the field of architecture. In celebration of our 2022 medallist, five different expert voices reflect on the work and impact of architect Peter Barber.

Missed Peter's Soane Medal Lecture? Catch up now on our YouTube channel.

Sadiq Khan Back to top

Mayor of London

Peter Barber doesn’t hide his politics, they proudly inform every aspect of his work. He wants to design a world where social housing is first rate, not last resort. Where many see a commodity, Barber imagines a community. And while society leans more and more towards atomisation, he encourages integration.

The philosophy underpinning Barber’s architecture is the notion that the street is the building block of a city – he isn’t just designing homes but designing London as well. His work complements our efforts to build a better London for everyone – a city that is fairer, greener, safer and more prosperous for all our communities.

If you live in London, the chances are you will have seen his creations and been left charmed. The innovative “tower” homes design for the McGrath Road development in Stratford for Newham Council rightly won him widespread acclaim.

As part of City Hall’s Small Sites x Small Builders programme, Barber also designed the stunning Beechwood Mews development in Finchley. On what was a tiny patch of wasteland, will stand 97 homes, half of which are affordable.

However, my favourite Barber project remains the alms houses of Holmes Road Studios (pictured above) – a beautiful Camden Council facility providing accommodation, training and counselling for homeless people.

Over many decades, Barber has witnessed London slide into a profound housing crisis. Homes became investments, rather than places to live. Rents are continuing to spiral. And a generation has all but given up on the dream of homeownership. It is all the result of catastrophic policy making, which we are now working tirelessly to fix.

With that in mind, maybe the enduring lesson we should take from Barber is how he returns to his projects to see how people’s lives have changed by the decisions he took.

London is now building council homes at a level not seen since the 1970s. As Mayor, I want us to continue that renaissance, and with many more Barber designs inspiring our city and enriching our communities.

Ferhat Ulusu Back to top

Ex-resident at Mount Pleasant, Peter Barber’s sheltered housing project for street homeless people

I first met Peter during a gardening session in the courtyard with the residents at Mount Pleasant.

From that time I would pop in to his office on King’s Cross Road, read about his unique architecture in the local and international press, visit the different sites where he designed ground-breaking buildings and follow the way he swings and sways on social media. He can hold blues tunes playing his guitar. No misses - every single time he wins the hearts of everyone who comes in contact with him. My first impression is of seeing a giant man approaching - you wonder how tall he is. Despite his height, he always remained down to earth.

Today, I would like to take this opportunity to say ‘a mega thank you’ PETER BARBER!

Thank you for your dedication to architecture, thank you for your generosity and your outstanding contribution to homelessness and so much love for its community and last but not least… you have always been there for me when I need it the most. THANK YOU!

Congratulations for winning this award like a real Boss would…!

Polly Neate CBE Back to top

Chief Executive, Shelter

In 2019, following a major research project, Shelter set out its vision for the future of social housing.

Homes that people can be proud of, homes that are good quality, energy efficient, and most important of all, truly affordable to live in. And as rents and bills go up, the combination of these qualities is all the more important. It’s not acceptable for homes to be good quality but expensive in one part of town, and cheap but shoddy in another. We need architecture, design and planning that makes a dent in our housing emergency. Peter Barber is someone who clearly understands this.

While many of us campaigners hark back to the ‘golden age’ of social housing in the post war era, Peter’s ideas look forward always aiming to paint a vision for better housing and stronger communities that is rooted in the very real challenges we face today.

But it’s not only a vision for the future that our movement needs. We need proof that it can be done now.

Peter and his team’s buildings are showing that when political will and good architecture meet, it is possible. Beautiful and affordable homes can become a hallmark of council housing and we can deliver for those at the sharpest end of our housing system.

It's great to see this award go to someone with not only a vision for architecture, but with a vision for a fairer housing system too.

Vicky Richardson Back to top

Head of Architecture and Heinz Curator at the Royal Academy of Arts

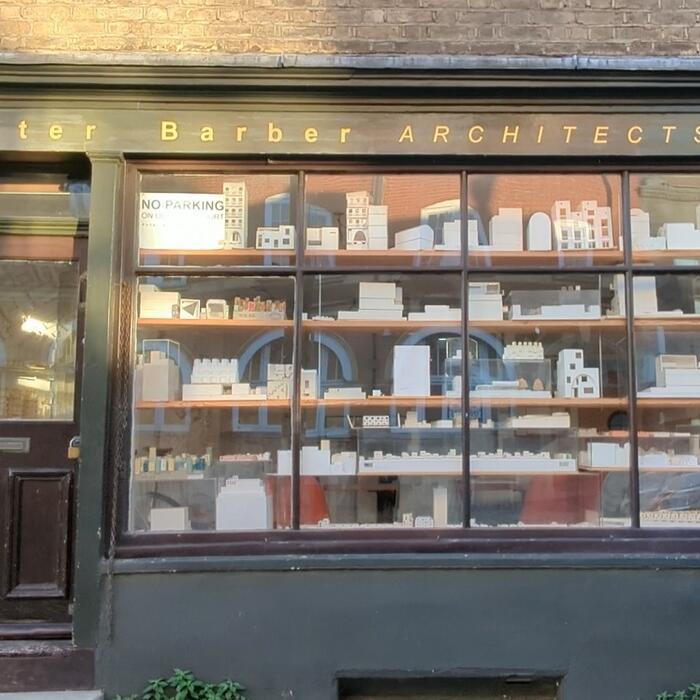

When an artist or architect is elected as a Royal Academician, they are invited to give a work to the RA Collection. Sir John Soane, for example, gave a magnificent watercolour perspective of his 1794 design for the House of Lords. I recently had the pleasure of visiting Peter Barber’s studio to discuss his choice of ‘Diploma Work’, following his election as an Academician.

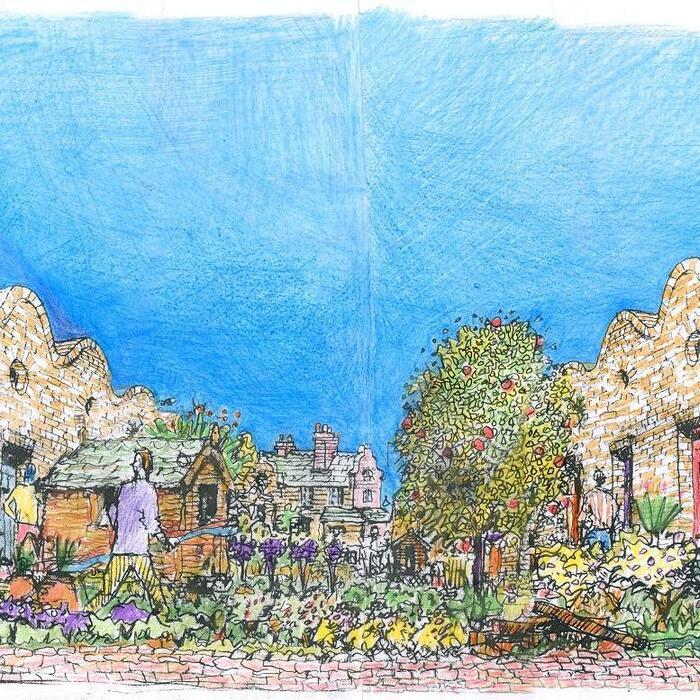

We began by talking about the practical challenges of conserving architectural models. Sitting in the window of his studio in King’s Cross where he has been based for more than 20 years, we were surrounded by beautiful white cardboard models hanging from and resting on almost every available surface. Some of them are dusty and coming apart at the joints: they were not intended to be collected as art works, but to be the focus of conversations with residents and clients. Ranging in scale from designs for groups of houses to new ideas for cities, Peter’s models and drawings are evidence of a career dedicated to social housing.

Our meeting reminded me that a few years ago I wrote about one of his housing schemes in west London for the Evening Standard. The editor sent me off to Hafer Road to meet the residents and ‘get the story’ from their point of view. They told me that Peter had turned up to the first meeting with a large model - a complex three-dimensional puzzle of accommodation and courtyards. He had listened to their individual requests and designed an ingenious building that provided for everyone’s needs and gave each resident their own outdoor space.

A few years later, enjoying their new homes, it was clear the building had transformed their lives. Peter himself told me that at the opening of Hafer Road, there were tears of emotion. I’m fairly sure that if you visited any of his housing projects you would hear the same response.

Whatever Peter chooses to give the RA as his Diploma Work, it will be housing fit for lords.

Phineas Harper Back to top

Director, Open City

“A shadowy street with a little kick, tapering and narrowing suddenly before opening through an archway into the corner of a sunny square...mmm, nice!”

Most architects do not write like this. Most architects do not wear leather, take their sons to WWE wrestling matches, personally hammer out jazz piano at their office summer party or plaster the door of their nineties flat share with gold leaf. Most architects are not Peter Barber.

For me, a great strength of Barber’s vital and vibrant work is his infectious ability to ground his clear-sighted, urban, economic and historical analysis in the accessible language and character of unpretentious, joyful, ordinary life. His buildings, like his writing, embody this seemingly contradictory synthesis; stridently expressive armatures that are nonetheless permissive and generous. Loose enough to allow residents individual self-expression within the nooks and vaults of their exuberant thresholds, yet robustly coherent additions to the formal streetscapes they sit within.

As cynics stoke division from the columns of British broadsheets, Barber’s work proves that learning from difference is more enriching than tribalism. He shows us there needn’t be a culture war between the high Modernism of Alvaro Siza and the trad bricky English terrace; that we have something to learn from the dense demolished old town of Great Yarmouth and Brum’s back-to-backs, just as we do from Le Corbusier. Barber deftly and gregariously straddles contradiction, winning fans across the political spectrum from Owen Jones to Nicholas Boys Smith.

Above all Barber’s unique body of work is underscored by his unflinching commitment to a social mission. He is furious at the cruel, inequity of British society and channels his deep love of and skill in the craft of urbanism to do something about it.

A sorely needed counterpoint to the tepid, aesthetic and moral banality which is common elsewhere, Barber and his team imbue their projects with purpose, character and equity… mmm, nice!