Each year the Soane Medal & Lecture is awarded to a practitioner, historian, educator or writer who has made a lasting contribution to the field of architecture. On the occasion of the 2019 medallist, five different voices from architecture reflect on the work and legacy of Kenneth Frampton.

Juhani Pallasmaa Back to top

At Machu Picchu

I vividly recall Kenneth Frampton almost running up the steep footpaths and stairs at Machu Picchu on our two visits to this legendary fifteenth-century Inca citadel. I remember him leaning against the semi-circular wall of the Temple of the Sun and silently contemplating the Intihuatana calendar, while surrounded by clouds. I can also see him studying the magnificent polygonal masonry work at Sacsayhuamàn, standing by the experimental farming terraces of the Incas at Moray, and walking in the walled streets of Cuzco, once the capital of the Incan empire, observing the intricately joined stones.

I also recall our forking conversations on architecture and art, history and philosophy, politics and friends during this trip. On our way to see the farming terraces, we discussed the enigmatic statement of the Catalan philosopher Eugenio d’Dors: ‘Everything that is outside of tradition, is plagiarism.’ I had read this provocative sentence in the memoirs of Igor Stravinsky and Federico Fellini, and Ken would later refer to it in his book Labour, Work and Architecture. In a Fellinian spirit, we watched a group of tourists as they danced down the corridor of our tiny train as it wobbled and wound down the steep mountains towards Machu Picchu. Another unexpected experience was a Peruvian bullfight in Lima, at the time bullfights were banned in Catalonia.

Our first visit to the world of the Incas took place after a conference on architectural education at the University of Lima, organised in 2001 by Frederick Cooper, the energetic dean of the architecture school. We happened to lecture in Lima just a few days before the collapse of the World Trade Center in New York. I returned to St Louis on the eve of the catastrophe. Ken was flying the next day to New York. His plane was diverted to Atlanta, and he was obliged to wait several days before he was taken to New York by bus.

Our second visit to Cuzco took place exactly ten years later, in 2011, as jurors for the New Faculty of Engineering of the Technical University of Lima. The competition was won by Grafton Architects, from Dublin, who were later awarded the 2020 Pritzker Prize. The project is an elevated, open and continuous multi-level structure that echoes the ambience of the Inca citadel, embraced by clouds.

Juhani Pallasmaa is an architect, professor emeritus (Aalto University, Helsinki) and writer.

John Miller Back to top

Kenneth Frampton, Architect

Ken has been one of my closest friends since we both enrolled at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1950. After seventy years there is much to reflect upon, too much perhaps in a few lines.

His reputation as a writer on architecture is well known. What is perhaps less known, is that he was also, however briefly, a practising architect.

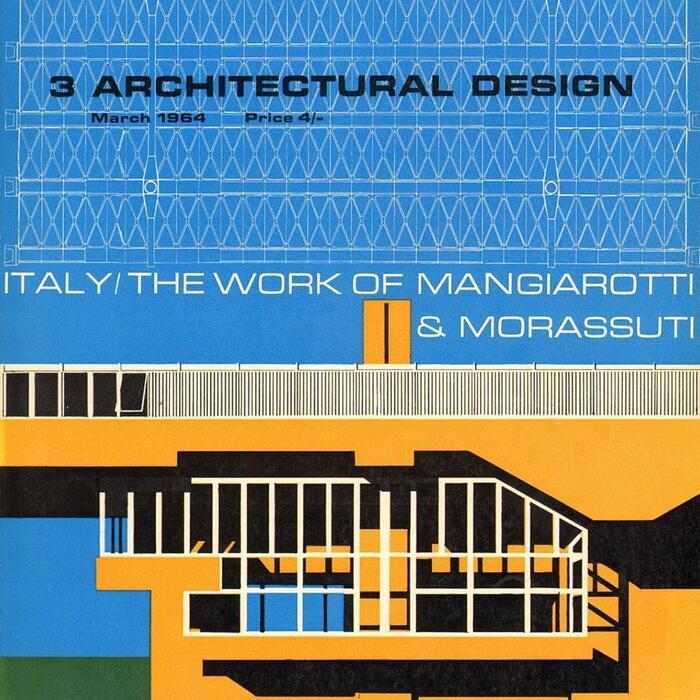

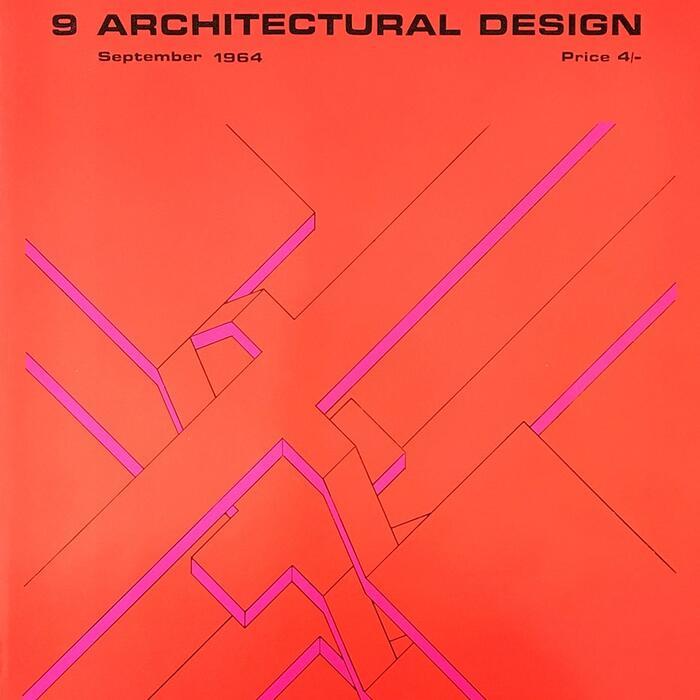

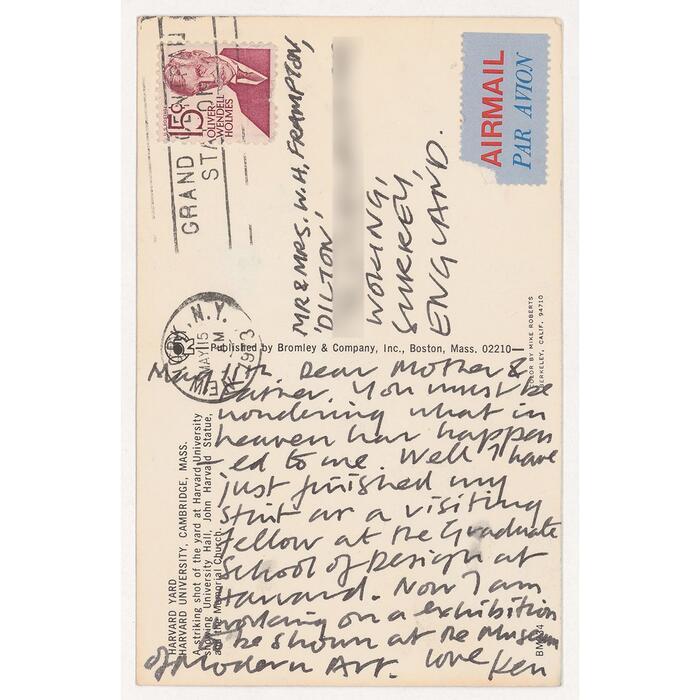

Before he took up the pen in earnest, Ken joined Douglas Stephen’s practice in the early 1960s. This was during his time as technical editor at Architectural Design, where he produced a series of memorable, brightly coloured monthly covers with abstracted architectural themes.

Douglas Stephen was a generous employer and friend, and Ken, then in his early thirties, was entrusted with the design of an apartment building in Craven Hill Gardens, Bayswater, and the supervision of its construction through to completion.

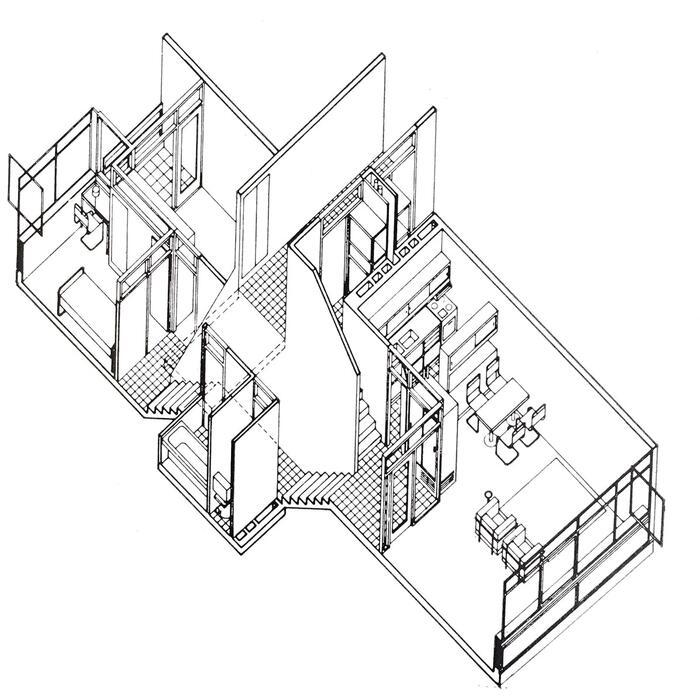

The brief called for a maximum number of two- and three-room maisonettes, to be sited at one end of a central public square, surrounded by nineteenth-century terrace houses.

It is a remarkable work. The exterior of the eight-storey apartment building is strikingly rational, with six stacks of recessed balconies to both long elevations. At the end of the building is a highly articulated entrance core and lift, and stair access tower. The entrance core is ‘tethered’ to the surrounding pavement by a narrow, covered ramp that runs up to the street. In those days, you could imagine a resident arriving on a rainy evening by taxi and making the walk to their door without ever feeling a drop.

Instead of external access galleries, so characteristic of current high-rise practice at the time, Ken proposed wide central ‘public’ corridors, which run the length of the building, from the lift and stair tower to an escape stair at the other end. This is essentially a reference Le Corbusier, and more specifically, the section of the Unité d’habitation.

It is ingenious if complex, and unexpected in the context of the rationalism of the exterior. As students at the AA, ten years before, we had been obsessed with ‘half level’ planning. The advantage was thought to be the omission of ‘dogleg’ stairs and half landings. This enabled spaces to easily ‘swim’ into one another, by means of short single flights. But for a builder, before the dividing partitions are in, equal half levels meant there was always some doubt about where an apartment might end or begin. Ken’s design certainly challenged the contractors. I remember the foreman, faced with these immaculate drawings, shaking his head and remarking, ‘That young Kenny…’ – well, you can imagine the words that might have followed.

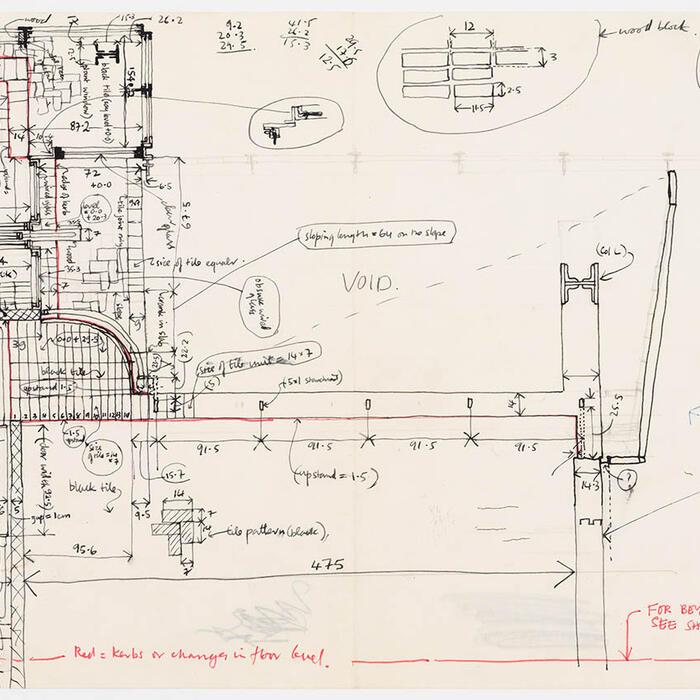

The drawings that Ken provided for the contractors were unusual. Instead of showing floor plans of each maisonette type independently, floor levels, sections and elevations of the building were drawn in their entirety, and in great detail, even down to floor tiling. In a sense they were a description of the completed building – an analogue of the building to be, rather than instructions to a contractor for its construction.

Craven Hill Gardens was completed nearly sixty years ago. It is an impressive work, which I continue to admire, and it richly deserves its 1998 Grade II listing.

John Miller was educated at the Architectural Association and after working as an assistant to Leslie Martin, Colquhoun + Miller was founded in 1961. The practice became John Miller + Partners in 1990 on the retirement of Alan Colquhoun.

Shelley McNamara Back to top

A Way through the Fog

What does it feel like to be written about by Kenneth Frampton? This was one of the questions posed when we were invited to write this piece. Our first monograph was published by Gandon Editions in 1999. When we phoned Kenneth Frampton to ask if he would write a piece about our work he said, ‘send me some drawings!’

We did not know him well at the time. We were given a time to phone again and, full of apprehension, we were relieved to hear his response which was economical: ‘Beautiful work, I will write a short piece.’ His short essay was on the whole, extremely positive, but embedded in there was a sharp and deserved criticism of a project where we had clearly lost our way.

When writing about the Bocconi University project in Milan, he kept making sketches on the occasion of his visit to the building. The work was interrogated as were the architects. Flaws were spotted. When he asked, ‘Could you not have made a better handrail than this?’ you knew that he was measuring what he saw against all the handrails in all the world in all the great buildings he knew so intimately.

We were acutely aware, on the occasion of this site ‘inspection’, that we were in the hands of a practising architect – an intellectual who has designed and built buildings. He was questioning as an insider, someone who knows the score, the ‘plight’ of the architect in the struggle to make a building which is in the end a sum of imperfections.

Given this reality, what sustains the making of a building – what delivers it into the realm of architecture – is the vision, the strength of the idea, the passion and feeling invested by everyone involved.

Kenneth Frampton’s experience as a practising architect makes him, in our view, both more sympathetic and more critical, and therefore a positive response from him is all the more treasured.

His written piece on our building was indeed treasured by us. It was poetic, expansive, soaring through the heights of spatial language, historic reference, societal meaning.

For so many years, he has dissected great buildings and revealed their mysteries and qualities to us. Their origins, their place in the continuum of tradition, their tectonics within the vast language of construction. He reveals his own passion for craft, for integrity, for the haptic sensual component of a building. He is a custodian of the core values of architecture.

Kenneth Frampton tells you like it is. What is good and what is not. What is confused and what is clear. He has been our way finder in the fog of making work.

Shelley McNamara co-founded Grafton Architects with Yvonne Farrell in 1978. They are the 2020 Pritzker Prize Laureates.

Tony Fretton Back to top

A Global Outlook

I saw Kenneth first in the Lecture Hall of the Architectural Association School in London, where I was a student and he was standing to run for the Head of School. He was elegant, lucid and highly intelligent and would have taken the AA in a very interesting direction. But the AA being what it was, Alvin Boyarsky won with an ambiguous programme and an adroit reading of the audience, leading to years of brilliance of another sort. So along with Alan Colquhoun and Robert Maxwell, Kenneth Frampton was lost to us but gained by the US.

There his political sense and feeling for social justice has never dulled and he has maintained a scrupulous voice for architecture as an intellectual and constructive discipline, writing theory with direct value for practitioners in contrast to the etiolated scholasticism of East Coast Academia.

His intellectual generosity and instinct for the architectural developments in Europe have led him to teach and speak widely here, and among other things to write the essay for an exhibition of my own work at the AA. Our acquaintance grew as we crossed paths at EPF Lausanne, the Berlage Institute and TU Delft. His presence along with Robert Maxwell, Jacques Gubler and Stanislaus von Moos at the celebration in the AA of Alan Colquhoun’s work showed the greatness of his generation, and above all his special combination of intellectual reserve and generosity. My meetings with Ken have not been frequent and have occurred over a long time, but his kindness and greatness are always present.

Tony Fretton is a principal, with James McKinney and David Owen, of Tony Fretton Architects London. From 1999–13 he was Professor, Chair of Architectural Design-Interiors at the Technical University of Delft.

Zhu Tao Back to top

Frampton = Frankfurter + French Fries

Kenneth Frampton once told me that ‘as an architectural intellectual, I suppose, one eventually must choose between Frankfurters and French fries. Peter Eisenman has chosen French fries, and I, the Frankfurter.’

This was not literally a question of what to eat. He was applying an old joke of critical theory to architecture. On the philosophical spectrum, Frankfurters, like the food itself, are the seriously uptight – Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse, Habermas. French fries, on the other hand, are the provocative and ironic – the Foucaults, Derridas, Bartheses and Deleuzes of the world. Salty, stylish, bendy, more-ish. Frankfurters were unhappy with how the French Fries ‘aestheticised’ everything. French fries complained that Frankfurters were too ideologically stiff.

But to give my former teacher more credit, I don’t think he has ever really subscribed to either culinary camp. Kenneth Frampton is far more complicated than his self-description. Certainly, compared with Eisenman, he is very Frankfurter-ish, insisting that architecture only acquires meaning when an innovative formal project aligns with a progressive social project. But, compared to Manfredo Tafuri, Frampton might appear too French-fried. For if, following Tafuri’s logic, all progressive social projects are doomed to fail, why does Frampton still maintain faith in the redemptive power of architecture’s formal beauty?

Among Frampton’s published works, I would say that A Critical History tastes Frankfurter-ish, while Studies in Tectonic Culture and his numerous essays promoting ‘critical regionalism’ contain more of a ‘French fries’ flavour. One can also identify in Frampton’s global readership two groups of the gluttonous: scholars devouring the former and architects chewing over the latter. The former offers a new kind of historiography; the latter inspires one to pursue good design. In a way, his career has fed us all – and through him I have learned to treat architecture as a balanced meal of both protein and carbs.

Zhu Tao is a former student of Kenneth Frampton. He teaches architecture at the University of Hong Kong and practices architecture in China. He received his Master of Architecture and PhD in Architecture History and Theory at Columbia University.

Header image credit: Kenneth Frampton, c 1981, the year ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism’ was first published, photo Silvia Kolbowski. Kenneth Frampton fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, gift of Kenneth Frampton