As one of Britain’s most acclaimed architects and founder of Peter Barber Architects, 2022 Soane Medallist Peter Barber’s practice focuses on social housing and urban planning.

He has been widely celebrated for his inventive approach to design, delivering innovative housing which is both high-quality and affordable. Barber has also developed a number of speculative projects which respond to issues including the housing crisis and the revitalisation of de-industrialised areas.

In recent years Peter and his firm have received several awards, including a lifetime achievement award from the Architects’ Journal and IBA Neave Brown Award for Housing 2021. He was awarded an OBE for services to architecture last year and elected as a Royal Academician in January. Alongside his practice, Peter lectures on architecture at the University of Westminster and was recently invited by the government to lead a discussion on "Designing for Better Public Spaces" with a team of top built environment professionals.

Read on, or watch Peter's lecture below.

The lecture

Forty years of thinking about cities has taught me that there are tonnes of ways to be an architect.

There are numerous hats that we can and should wear – abstract and analytical, political, sensual, social, artistic, pragmatic even. We need to be sociologist, citizen, geographer, activist and urbanist – master-planner-structuralist and Situationist both.

I’d like to start by outlining 12 ideas and thoughts which aim to tease out an ideological and political context for our work. These quotes, images and observations capture the atmosphere and ethos of what we do, and they provide a moral compass for our design process. I’ll then describe how these ideas find expression in three of our built projects. I will finish by talking about my sketchbooks and a series of theoretical or speculative projects/ideas, including 8,000 Mile Island – our vision for an array of maritime farms and offshore green energy plants tracing the coastal outline of our island from the Orkney Islands to the Isle of Wight and back. It offers a vision for a food and energy self-sufficient UK.

The housing crisis Back to top

I

"Perhaps the most democratic achievement of elected government in the twentieth century was the building of council housing to let at rent that the workers could afford. The endeavour was the essence of social democracy. It was socialist because it favoured the poor and it was democratic because the landlord was the elected authority responsible to the tenant."

Paul Foot, The Vote, 2005

The UK was broke in the aftermath of the Second World War, and yet successive governments still found the resources not only to fund the National Health Service but to build 150,000 homes annually. By 1975, nearly half the population enjoyed the benefits of living in council housing. In the intervening years, this policy has been reversed with a series of disastrous housing acts. Governments of both political complexions have abandoned their commitment to social housing. Since 1979, half of all public-owned land has been sold into private ownership and two million homes have been sold, at discounted prices, under the nonsensical ‘right to buy’ scheme. Today, only around eight per cent of the population lives in council housing.

Consequently, in London alone there are currently: 170,000 homeless people (Shelter’s robust minimum figure); 8,000 rough sleepers – a total that has doubled in the last four years; 30,000 empty homes; and 150 families losing their homes each day. At the same time we have seen an exponential rise in property prices and the cost of private-sector rentals – an increase of 259 per cent over the course of the last 10 years.

In my view, housing is basic infrastructure, and not a commodity, and the control of the land economy and housing production has to be a matter for government – much as it was in the middle part of the last century.

Three simple policies would decommodify housing and go a long way to ending the housing crisis: 1. Introduce private sector rent controls; 2. Halt the selling of council houses under ‘right to buy’; 3. Create 150,000 council houses a year funded by direct taxation.

It would make ecological sense that a substantial proportion of these houses ought to be refurbished from the enormous stock (half a million in recent estimates) of empty homes. Double glazing, roof insulation, a lick of paint: job done.

It would be interesting to reflect on ways in which this new wave of council housing production might be devolved, bottom up or incremental.

II

Housing shortage? What housing shortage? There are currently 250,000 homeless people in the UK and over 500,000 empty homes. There is no housing shortage.

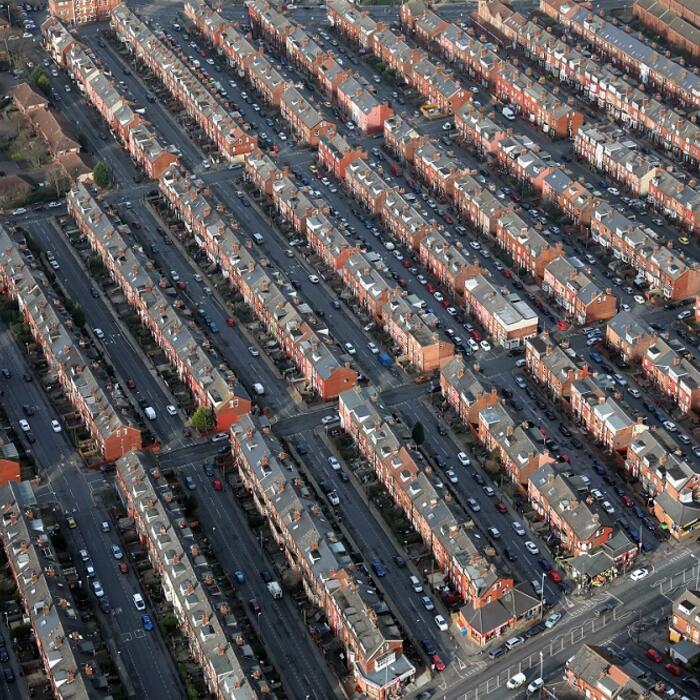

Outside London, in areas dogged by the collapse of the UK’s industrial and maritime economies, there are row upon row of empty houses; silent, deserted, street after street of boarded-up homes, entire urban areas, depopulated, jobless. These include former industrial cities such as Rochdale, Bolton, Burnley, Stoke, Middlesbrough and coastal towns, where multiple deprivation indices are the most shocking, such as Blackpool, Hull, Morecambe, Plymouth and Swansea, where 150,000 homes lie empty.

Equally shocking, in London there are 30,000 shiny new homes, empty, locked shut, never lived in. Cash cow, commodity, investment vehicle. These are testament to investor greed, the amorality of pension funds and the disinterest of wealthy overseas buyers. London’s land-bank-larceny property industry is the product of half a century of neo-liberal Government economic policy aimed at promoting the ‘housing industry’ as one of the principal drivers of economic growth.

And this is echoed on a smaller scale in second home and Airbnb ghost villages, empty 9 months a year, working people priced out, forced out in a maelstrom of holiday lets.

The housing crisis would be over if we:

- Instigate a massive programme of government investment in new productive industries, that would attract employment/people back to our most hard-hit depopulated urban centres, where there are hundreds of thousands of empty homes waiting for them.

- Set up a Government National Housing Service with powers to purchase hundreds of thousands of empty homes in run-down areas. New Council Houses created through the refurbishment and improvement of empty and derelict property.

- Municipalise long-term vacant investment property.

The street Back to top

III

"…The passion for improvisation which demands that space and opportunity be at any price preserved. Buildings are used as a popular stage. They are all divided into innumerable simultaneously animated theatres. Balcony, courtyard, window, gateway, staircase, roof are at the same time stages and boxes… as porous as the stone is the architecture. Buildings and action interpenetrate in the courtyards, arcades and stairways. In everything they preserve the scope to become a theatre of new unforeseen constellations. The stamp of the definitive is avoided. No situation appears intended forever."

Walter Benjamin, One Way Street, 1924

Marxist cultural critic Walter Benjamin’s description of the culture and form of a street in Naples (above) captures beautifully the idea of a city animated by the activities of its occupants – by a spatiality that is permeable, that invites occupation. He gives us an intimation of the fragile and complex reciprocal relationship that exists between people and space, between culture and architecture. His message: without people and culture, space is inert.

Our projects work with the idea that space conditions, and is in turn conditioned by, society and culture and that architecture can create the potential for social action and activity. I always find it helpful to visualise how people might inhabit the spaces that we create, and I love revisiting our built housing projects to see how people’s lives are played out in their homes and in the courtyards and on the streets we have made.

IV

Housing accounts for 70 per cent of all the buildings in London. It’s what our city is made of. It’s what creates a hard edge to our streets, what surrounds our squares. Therefore, when we design urban housing we are designing cities. Designs for housing should begin as urban designs, driven in the first instance by our vision of a beautiful and socially integrated city.

Projects like Edgewood Mews in Finchley, London, and Donnybrook Quarter in Hackney, London, contain housing, but more fundamentally, they are a celebration of the collective life of the city.

V

I’m for street-based neighbourhoods. Streets are an ingenious and effective means of organising public space. Axial streets especially, being easy to understand and navigate, can help to create a city that is well integrated, both spatially and socially.

Picture the experience of a stroll along the North Laine in Brighton (below, left), an unremarkable but successful street with characteristics we can learn from:

- It is well integrated into the spatial fabric of the city, as part of the network of streets that make the city permeable and provides strong visual and spatial connections between adjacent yet socially diverse neighbourhoods.

- It is narrow, concentrating the public life of the area into a very limited space. It brings together people of diverse social, economic and cultural groups and creates the potential for a colourful social scene.

- The buildings that bound the street house a mix of uses – retail, leisure, business and residential – that create a vibrant local culture and 24-hour occupancy.

There is a strong visual connection between the buildings themselves and the street. This means that every inch of public space is overlooked or naturally policed. It is hard to imagine a mugging or robbery taking place here. Narrow building frontages and numerous front doors create visual diversity and the potential for occupiers to personalise their space.

Now, compare this to Pitfield Street, in East London (above, right), where you walk 50m up the street and turn right through a gap between buildings to enter a very different world – the vast hinterland of inter- and post-war housing estates that stretches across Hoxton. The designers of these estates eschewed the street in favour of a spatiality that has blighted the lives of thousands of residents for three generations:

- The spaces between buildings create no useful routes across this part of the city, forcing people to make lengthy and inconvenient detours around them.

- Dead ends, blind alleyways, burnt-out garages and paladin stores block off any views into, or routes across, the estates. Concealed from view in this way, one of London’s most socially disadvantaged areas has become segregated from the rest of the city – a ghetto.

- The estates are laid out as a series of objects dotted around in acres of unused space: some concrete pavers or tarmac here, a patch of grass there. Such large, dispersed spaces tend to dissipate social activity, limiting the potential for people to meet or even to see fellow residents. Deserted most of the time, they create an environment which tends to isolate people and increase their vulnerability to crime. Some of those living on the estate are afraid to leave their apartments. Most affected are the elderly, racial minorities and women.

Against this, I like to try and arrange our projects as a network of streets often interspersed with little public squares and gardens. I aim to align streets so that they create handy shortcuts and strong spatial and visual connections with adjacent neighbourhoods.

I like to imagine narrow streets which concentrate the pub¬lic world into a fairly limited space, bringing together lots of different types of people. And it’s nice to think of narrow building frontages and numerous front doors creating visual diversity and the potential for people to personalise the space outside their homes.

In his 1925 essay, ‘Urbanism’, architect Le Corbusier said, ‘a street is linear factory’ – typically hyperbolic. But it’s good to think of a productive city, houses over workshops, shop windows and loading bays, clobber at the kerb, messy cross-programming – as in places such as pre-war London, Marrakesh and Old Delhi.

Typologies and theory Back to top

VI

I am interested in medium-rise, higher-density housing, and often try to explore the possibility of achieving this with houses instead of flats.

We like to experiment with unconventional housing typologies. Some of them are quite obscure or belong to a pre-modern vernacular – the Tyneside or cottage flat, back-to-back houses, courtyard house types, double and treble stack ‘walk ups’ – not to mention the hybrid terrace/courtyard notched terrace, which I nicked from architects Adolf Loos and Josep Lluís Sert.

Where higher-rise apartments are required, it seems to me that pre-modern tenement housing and mansion block typol¬ogies are good models. They define a clear and unambiguous edge to the street and tend to concentrate circulation within the street itself, with numerous and regular points of street access and minimal interior circulation – think also of architect Neave Brown’s Alexandra Road estate in Camden, London.

VII

Filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein said that Greek urbanists were the first great cinematographers. While I’m designing I sometimes try to imagine our schemes as a screenplay, a sequence of views, picturesque, filmic even: long, lyrical tracking shots, a shocking jump cut, Sergio Leone-style shifts in scale from detail to widescreen panorama – silhouette, close up, perspective shifting, space unfolding, picturesque, sensual – a shadowy street with a little kick, tapering and narrowing suddenly before opening through an archway into the corner of a sunny square… mmm, nice!

It’s good in this context to think also of theorist Guy Debord’s Situationist dérive and psychogeographic maps, or critic Charles Baudelaire’s flâneur – the city and its streets understood and experienced ‘on the ground’, at eye level.

VIII

I love straight streets in grids – stretched, square, diamond, triangular, hexagonal grids. Let’s take a look.

IX

Jemaa el-Fna, the extraordinary public square embedded in the medieval walls of Marrakesh, Morocco, in my view exemplifies what public space is – or at least what it can be.

Like all public space it is unique because it belongs at the same time to no one and to everyone – to old and young, rich and poor, tourists and locals alike. It’s a place where people can express themselves with relative freedom.

Jemaa el-Fna has no monuments and is almost entirely surrounded by unexceptional buildings. For much of the day it remains fairly quiet. However, in the cool of the evening the teeming alleyways of the old town spill into it and a tumultuous scene unfolds.

Little mobile kitchens appear from nowhere; people form circles around fire-eaters, acrobats and story-tellers. Theatre troupes perform on hastily erected stages. There are snake charmers and oud players, drum bands and fireworks. This is an architecture of festivity – ephemeral, mobile, in flux – foregrounded by people, its message embodied in its name: Jemaa el-Fna translates as ‘Mosque of Nothing’. I love the idea of public space being a ‘mosque of nothing’: open, unprogrammed, where people can be themselves.

Behind the photographer is Jemaa el-Fna’s antithesis, the Grand Mosque of Marrakesh – metre-thick walls, solid, immutable, unchanging.

Celebrating the everyday Back to top

X

In The Practice of Everyday Life, philosopher Michel de Certeau says that space is practised place, everyday narrative, a word caught in the ambiguity of actualisation, on streets, in apartments and in the most intimate of domestic habits.

It’s useful to think about small things, everyday habits, domestic rituals, the turning of a door handle, footsteps on the stairs, the view from a window seat.

This preoccupation with lived experience and pleasure taken in our intimate relationships with our environment is evident in the architecture and ideas of architect Peter Zumthor in Thinking Architecture (1998): ‘I remember the sound of gravel under my feet, the soft gleam of the waxed oak staircase…’.

Our 1993 apartment interior in London, known as Gadget Apartment, celebrates everyday things and ordinary domestic rituals. It is homespun, assembled from oddments found in local skips, tips, junk shops and stuff left lying around. Cheap, handy, bespoke, the residue of previous construction and destruction.

Mono-gold door

At the threshold between the public world and the apartment interior, the inside face of the front door is cov¬ered in gleaming squares of gold leaf found in a junk shop.

Bath tidy

Copper pipe wraps the bathroom wall as radiator, towel rail and handy hook for razor, soap dish and tooth¬brush. No home should be without one!

Tap and soap dish

A tap assembled from bits of old taps and a spiral coat-hanger wire soap dish.

Match shelf

A tiny wire shelf so you know where your matches are.

Wok-hob

Two second-hand wok burners and some mesh out of a skip.

Metachron B1 table (with Ben Stringer)

A dining table assembled from a triangle of broken glass and three traffic cones, all found in the street.

XI

In the 1950s the Great Yarmouth Corporation embarked on the destruction of the town’s historic centre, 35 acres of tiny streets and alleys known as the Yarmouth Rows, home and workplace to over 18,000 people – extraordinary architecture, Elizabethan and Georgian, but in their view ‘an insanitary and utterly unsatisfactory form of development which could not possibly be retained’. (The National Archives, HLG 71/2222).

Slum clearance programmes like this resulted in the demolition of vast quantities of back-to-back and terraced housing in the Midlands and the North of England, the sweeping away of serviceable and popular tenements in Glasgow and Edinburgh, the bulldozing of great swathes of street-based housing from Brighton to Newcastle.

Sixty years on, the same functionalist planning culture still prevails, favouring a dispersed, suburban, anti-social spatiality. Tick-box policy enforced through generic design standards, overlooking distances, car parking minimums, idiotic daylight, sunlight and air-quality indicators. Urbanism measured in habitable rooms/hectare, decibels, square metres and lux.

I would like to see radical new planning policy designed to encourage compact, continuous, urban form – a densely packed, convivial, congested city of intimately scaled streets and alleys where people from all different backgrounds could live alongside one another, where narrow streets compress and intensify the urban and human experience. In short, a socially and ecologically sustainable urbanism structured by idealism, rather than net-twitch neuroses.

Who we are Back to top

XII

"Peter Barber Architects…more of a dinner party than an architect’s office."

Catherine Slessor, The Architectural Review, 2019

There are six of us at Peter Barber Architects. We have worked together for many years. We place a great deal of emphasis on clear communication and easy working relationships – friendships in essence. Every birthday is marked with a meal out, and we have two big parties a year. We try to have an annual trip away to look at cities/architecture abroad.

We wanted our practice to remain small because we feel that we can be more effective if we can sit around a table together. We are quite unhierarchical. We try to be creative rather than corporate.

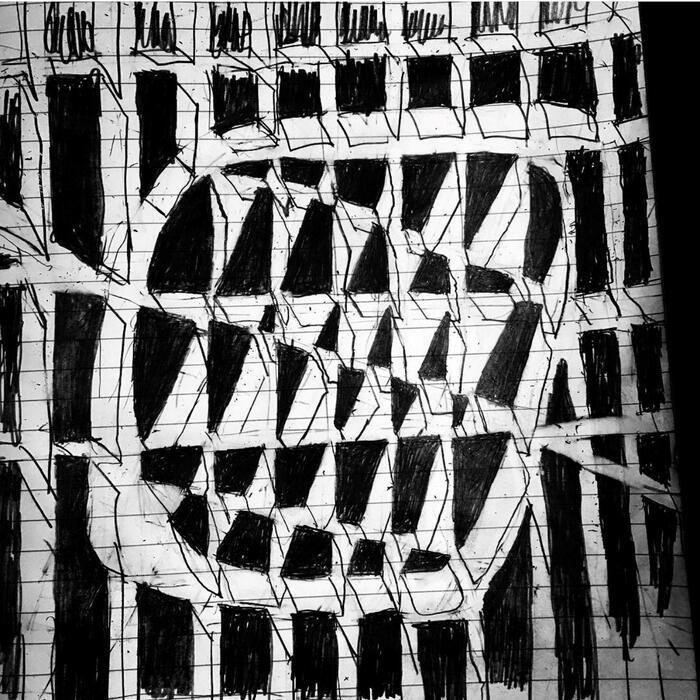

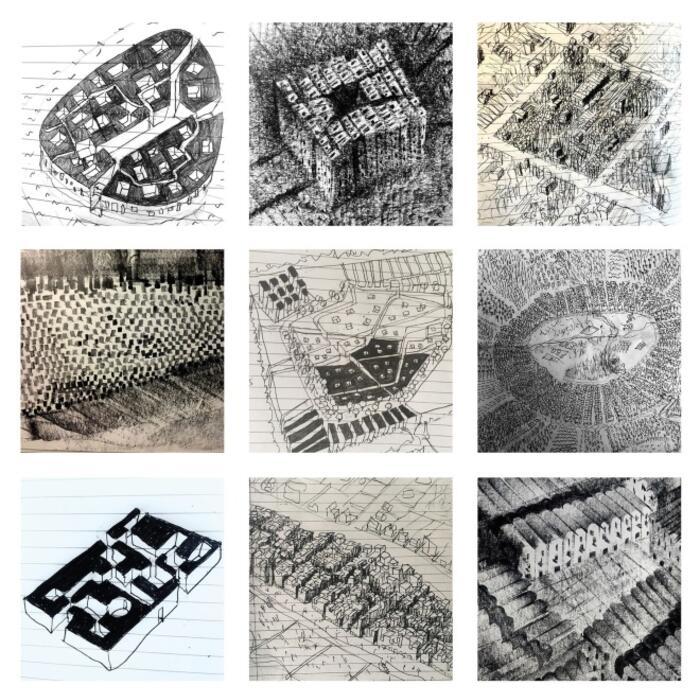

Our design process is analogue, dynamic, exhilarating even. The computer generally has no significant role in the early stages of our projects. Instead we begin designing with simple handmade physical block/sketch models to explore urban form and to test building massing, always in context. At the same time we explore schemes very rapidly with numerous hand-sketched axonometric drawings, eye-level perspectives, plans and sections – the whole project as well as little moments, bits and details. The design emerges on see-through/detail paper, one sheet overlaid onto the next, each layer incorporating a modification, correction or development. Bits get lopped off and added on to the models…they’re pretty scruffy sometimes. As the scheme develops, models and drawings become more detailed, less sketchy and larger in scale until finally we know what we’ve got and we can ink the drawings up.

Our office is on a fairly busy street in central London. We occupy a small building with a pavement shopfront, where hundreds of working models produced over many decades – testament to our process – are visible to our neighbours and to passers-by. We have loads of visitors!

I ‘teach’ architecture one day a week and have done every week for 35 years. I welcome the clarity and logic, the radicalism and experimentation that still flourishes in the best of our academic institutions.

Sketches, dreams, visions Back to top

Instead of clinging to the funeral towers of metropolitan finance, ours to march out to newly ploughed fields to create fresh patterns of political action, to alter for human purpose the perverse mechanisms of our economic regime, to conceive of fresh forms of human culture…we must erect a cult of life; life in action, as the farmer and mechanic knows it, life in expression as the artist knows it: life as the lover feels it and the parent practices it: life as it is known to men of good will who meditate in the cloister, experiment in the laboratory or plan intelligently in the factory.

Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities, 1938

I am an inveterate sketcher, and it’s interesting to reflect with hindsight how little dreamy visions and sketches – thoughts produced in a reflective moment – find their way from time to time, quite often in fact, into our built work.

In this final section I would like to share some ideas from my sketchbooks – some thoughts and visions for our future. Architectural practice, the making of buildings in the here and now, demands that to a significant extent, we work within the programmatic and technical constraints, prevailing societal norms and ultimately the illogic of our neo-liberal economy and cultural system. By contrast my sketchbooks (and my work in academia) have provided me with a space to dream a little, to be speculative, theoretical, to cut loose and, in answer to Lewis Mumford’s heroic rallying cry, to wonder about a different kind of architecture, urban form and society.

My ‘One year 365 cities’ project (pictured above) was an attempt to design a city a day for a year, resulting in numerous short experiments in urban form, unusual materials and imagined lifestyles. Among these ideas is ‘100 mile city’, a project to encircle London with a new street-based linear city of factories, public build¬ings and 2 million houses. Another idea that emerged from the project is Village V/K 3C, a self-sufficient farming cooperative village in rural Wiltshire built out of earth from the ground on which it stands.

Most recently I’ve been thinking about an idea, still brewing, not yet fully formed, called 8,000 Mile Island. This idea encompasses the notion of a countrywide aquacultural and maritime industrial revolution that would see a ribbon of tidal barrages, offshore wind farms, giant floating tidal turbines, deep-sea fish and seaweed farms tracing our coastline from the Orkney Islands to the Isle of Wight and back. Such a project would bring renewed prosperity to our decaying, depopulated coastal towns and cities. It also offers a vision of a food and energy self-sufficient UK and an end to the housing crisis.

8,000 Mile Island arises out of a number of questions and observations.

- Could we be energy self-sufficient? We currently import half of our energy, most of it in the form of gas and oil from tin-pot dictators in the Middle East and from our friend in Russia. However, the UK is unrivalled in its potential for generating clean green energy. It is the windiest country in Europe, and it has the most powerful tides in the world – a giant 15 metres tidal range off the Welsh coast.

- Could we be food self-sufficient? Over half of our food is currently transported from overseas. Half of that comes from beyond the EU. The globalised food industry has the UK firmly in its grasp – food mile madness, collapsing biodiversity, small farmers displaced, pesticide run¬off, deforestation. This is a global industry which sweeps aside local, even national interests for maximum profit, and one which is blind to the climate crisis. The UK has an 8,000-mile coastline. Our land area is 95,000 square miles, but our territorial waters extend to three times that. Imagine a revolution in maritime food production.

- The extraordinary Rampion Offshore Wind Farm, located off the south coast and visible from the beaches of Brighton and Hove, currently generates energy for 350,000 homes. It cost 1 billion pounds to build. One hundred wind farms of a similar scale could satisfy the domestic energy requirements of the UK’s 35 million homes. The cost of all these? 100 billion pounds, or the same as HS2. Wind power currently satisfies 50% of our domestic energy consumption. Let’s finish the job.

- Let’s end the housing crisis once and for all. It’s easy. Refurbish 400,000 empty Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses in the midlands, in the north and in our coastal towns, as homes for these new industries’ incoming workforce. Let’s redeploy the million people needlessly employed in housing construction in the south-east to the making of 8,000 Mile Island.

Picture this: build one hundred 400-megawatt off-shore wind farms and range them around our shores. Interlace them with thousands of floating tidal energy turbines out at sea. Construct enormous tidal lagoons in our estuaries. Put miniature community-run, cottage-industry wave power machines and little barrages on rocky out crops and inlets on our shoreline in Cornwall, the Hebrides and Cumbria.

Let’s intersperse these offshore energy industries with enormous seaweed farms. These are already under construction off the coast of Norfolk, North Yorkshire and in the Southwest. Seaweed carbon sinks are Amazonian in their scale, producing food, a source of energy and munching carbon as they go. Give us hundreds of deep-sea coastal oyster beds, mussel farms, fish and lobster hatcheries – floating fish farms in the deep ocean producing hundreds of the thousands of tonnes of food and millions of gallons of fish shit fertiliser for supply to aquaponic farms.

Construct maritime research stations in a necklace around these islands. Link them to our coastal universities, adding to and sharing knowledge of these nascent technologies and processes for the benefit of everyone.

Imagine existing fishing fleets – their local knowledge, their knowhow and equipment co-opted into these burgeoning industries. Employ the infrastructure already existing in the UK’s declining off-shore oil and ship-building industries in Hull, Inverness and on the Clyde, and think of thousands of new jobs in tired old Blackpool, Margate, St Leonards, Southend-on-Sea and Newhaven. Think of the housing ‘industry’ redeployed away from the south-east and charged with saving and restoring hundreds of thousands of empty homes – whole streets and neighbourhoods currently abandoned, in decay, now buzzing with new life, activity and prosperity from the incoming workforce.

Let’s think carefully about how these nationalised industries might make the best of top-down strategic planning, organisation and funding by Central Government combined with devolved management, bottom up, employing local knowledge, practically, usefully and efficiently applied.