Each year the Soane Medal & Lecture is awarded to a practitioner, historian, educator or writer who has made a lasting contribution to the field of architecture. On the occasion of the 2018 medal, five different voices from architecture reflect on the work and legacy of Denise Scott Brown, through her seminal work – book and architecture studio – Learning from Las Vegas.

Beatriz Colomina Back to top

Learning from Denise

The best teachers are the ones who know how to be students. We learn the most from those who keep learning. In that sense, there is a shortage of teachers in architecture. Too many voices with answers. Not enough questions. The exceptions are rare and precious. We have all learned so much from Denise Scott Brown – and still do, because she has never given up on the polemical mission to be a student, to endlessly investigate and communicate. It is not by chance that so many Scott Brown and Venturi projects are ‘Learning From…’ projects: Learning from Las Vegas, Learning from Levittown, Learning from Pop, Learning from Brutalism, Learning from Hamburgers, Learning from Lutyens, Learning from Brink, Learning from Philadelphia, Learning from Aalto, Learning from Commercial Vernacular Architecture, Learning the Right Lessons from the Beaux Arts, Learning the Wrong Lessons, Co-op City: Learning to Like It – even Learning from everything, as in the English title of the little Spanish book, Aprendiendo de todas las cosas, where I first learned about the work of Scott Brown and Venturi when I was a student of architecture in Valencia, Spain.

Scott Brown didn’t just master the art of being a permanent student but turned that into a mode of teaching. The ‘learning from’ philosophy was established by the two studios taught at Yale between 1968 and 1970, which in my opinion represented the most innovative approach to architectural education in decades, an approach that has more recently been very influential, whether consciously or unconsciously.

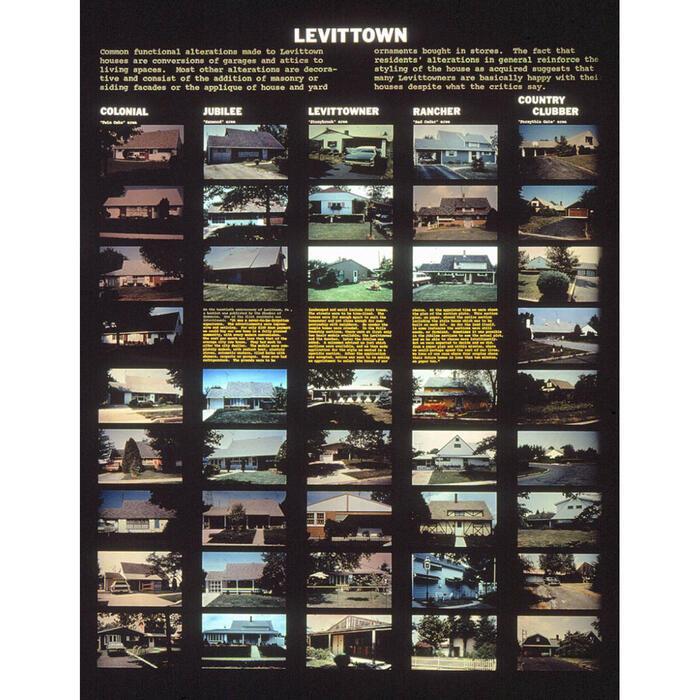

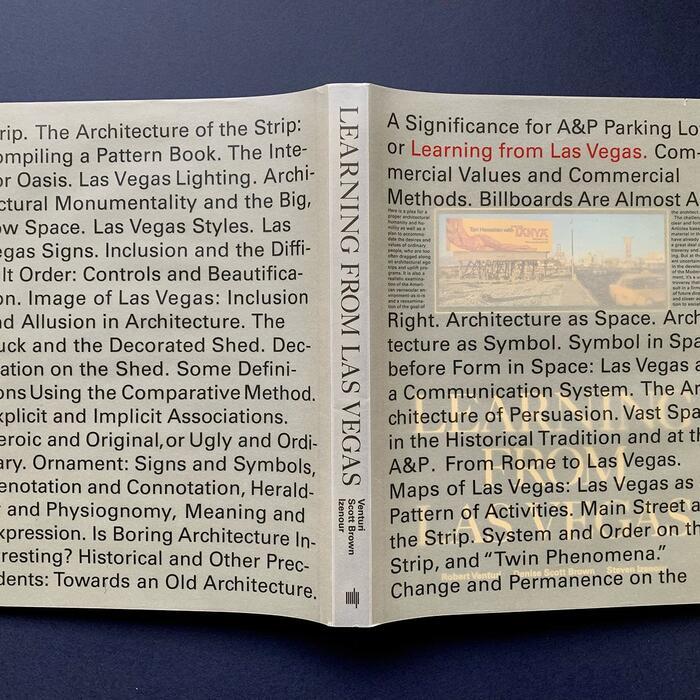

Following the famous Learning from Las Vegas studio at Yale in the fall of 1968, immortalised in the book Learning from Las Vegas published in 1972 by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour (who had been a student teaching assistant in the studio), Venturi and Scott Brown conducted in the spring of 1970 a less well known studio called Remedial Housing for Architects. ‘Or Learning from Levittown’ was later added in Denise’s handwriting to the syllabus in their archives, as if it had been an afterthought.

The insistence on ‘learning’ emphasises the idea that Scott Brown and Venturi’s mode of operation as architects is that of researchers – that all of their work is a form of research. They reinforce the idea that the designer is a researcher and a communicator. In fact, all of the research is about architecture as a form of communication. And isn’t it about time we acknowledge that all great architects are great communicators? That Le Corbusier would not have been Le Corbusier without the 50+ books he published; that Adolf Loos would not be Loos without his acerbic writings; that Walter Gropius, Alison and Peter Smithson, Venturi and Scott Brown, Aldo Rossi, Peter Eisenman, and Rem Koolhaas, are all architects first known through their writings?

But why the less heroic emphasis on learning in Denise’s work? A relentless philosophy of respecting what is being reacted against, a call for evolution rather than revolution. Learning then, is all about evolution, mutations of the gene pool that transform but never fully depart from the past and the present. But most importantly, the call to learn from is a call to show respect for whatever it is that the dominant architectural cultural disrespects: for example, the popular and the decorative. The learning from philosophy subverts the prejudices of the field. Denise Scott Brown has always threatened the field by embracing what it disdains. Hopefully, this much deserved honour does not dampen her disrespect for the field, which is her very strength as our teacher.

Beatriz Colomina is the founding director of the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University, the Howard Crosby Butler Professor of the History of Architecture and Director of Graduate studies in the School of Architecture.

Martino Stierli Back to top

Taking Pictures

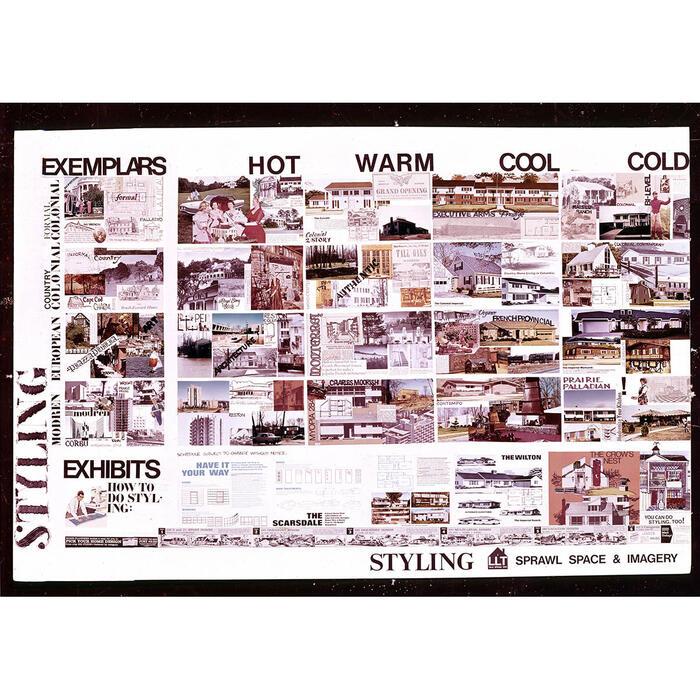

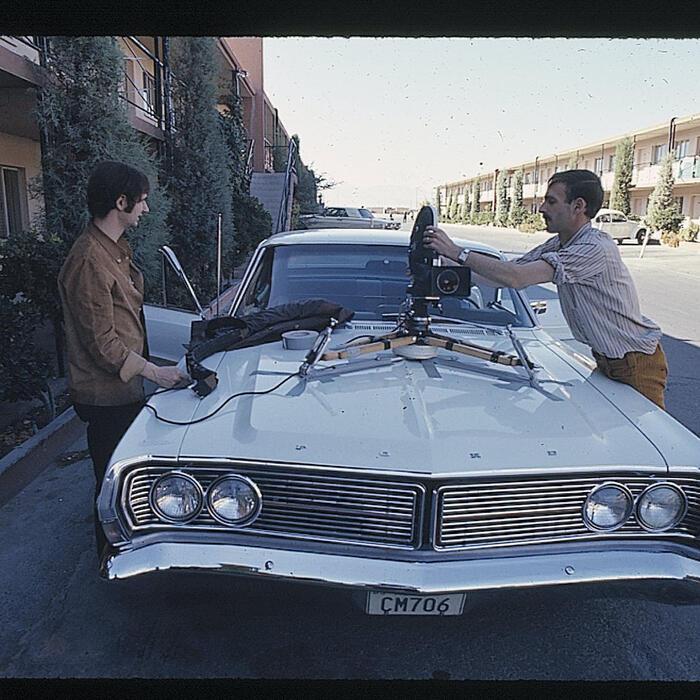

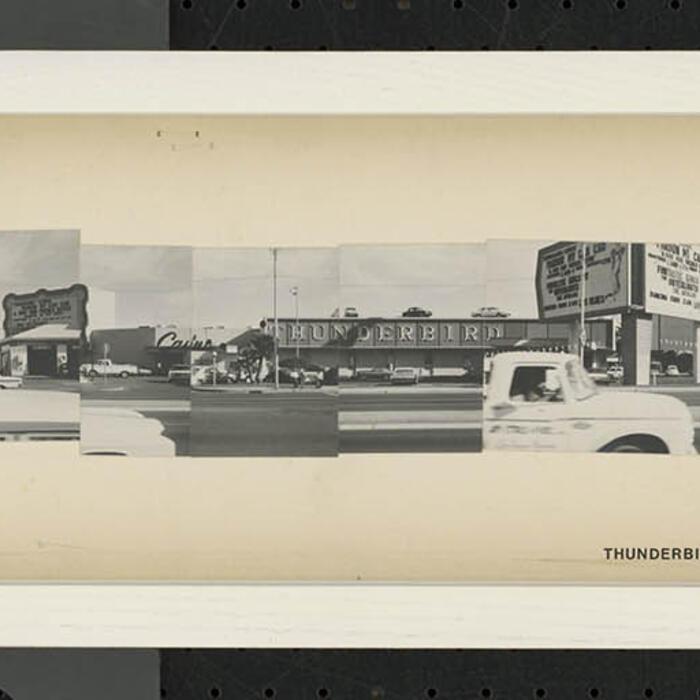

Denise Scott Brown pioneered the use of photography as an analytical tool to investigate, represent and understand urban form and the built environment. Learning from Las Vegas, first a pedagogical project at the Yale University School of Architecture in 1968 and later expanded to the seminal treatise, testifies to the methodological shift of the study of architecture and cities from more traditional approaches to photographic research. To consider the city ‘as is’, as opposed to what it should be in itself, constituted a major seismic shift – one that was amplified by the presence on the ground, the sense of a specific point of view (literally the position of the camera) and the speed by which this ground could be covered (by car and camera). All of this defines Scott Brown’s approach. In particular the 1972 large-scale first-edition of the book underlies to what degree she and her co-authors Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour, as well as their students, relied on photography and film in order to analyse and chart the suburban, car-oriented landscape of ‘urban sprawl’. Indeed, Scott Brown repeatedly stressed the need to devise new techniques of visual representation for new urban forms, in particular photography and film, which were more immediate tools for capturing a rapidly changing urban environment. The group’s research trip to Las Vegas resulted in many hours of film footage as well as thousands of slides, a number of which were reproduced in the book. By mounting a camera on the hood of a car and driving along the Las Vegas Strip, the group, for example, recorded a ‘deadpan’ moving image of the city; a method appropriated from the LA-based artist Ed Ruscha’s photography book project Every Building on the Sunset Strip. This instance is indicative of Scott Brown’s interdisciplinary approach to the study of urban form, which took into consideration not only artistic methodologies, but also those of related disciplines such as empirical sociology, visual anthropology and ethnology. In so doing, Learning from Las Vegas became the blueprint for subsequent attempts to accommodate urban research within architectural education, in particular in its use of photography as a means to analyse and document the built environment, and to understand it as the basis for design.

Martino Stierli is The Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Kersten Geers Back to top

Form and Content

When I was a student, Learning from Las Vegas was a looming presence. Published in 1972, it was (in its original format) a rarity in the 90s. I guess I liked it all the more for that; a book existing in the library, impossible to take home; it presented a world in semi-detachment. Gigantic, ambitious, radically designed, with bold graphics. It had an odd format to embrace the architecture of sheds and boxes. Perhaps the intrinsic monumentality of the book was both a lure and a McGuffin – a trigger, not least, for the revised edition of 1977: smaller, cheaper and an answer to the original, which, wrote Denise, ‘we felt belied our subject matter’. It sold you a graphic universe that was ultimately something else. The larger-than-life page layout and the Ruscha-esque documentation fuelled a dilemma that has since followed me – an ambiguity on form and content. Thus, the mystery of buildings which are supposed to be either ducks or sheds always puzzled me. My conclusion, then and now, reads like this: as long as buildings don’t look like ducks, they are sheds. That makes most buildings sheds. It’s a conviction shared by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi. Part III of that big original edition of Learning from Las Vegas, entitled ‘Essays in the Ugly and Ordinary: Some Decorated Sheds’, is a closet monograph of their own work. Neither ugly nor ordinary, it collects ‘decorated sheds’ of their own making. Still today (and I have some personal experience with this) it stands as the best monograph of their work. If proper architecture is indeed a shed, then perhaps a duck is a McGuffin.

Kersten Geers is co-founder of OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen in Brussels. With Jelena Pančevac and Andrea Zanderigo he edited The Difficult Whole: A reference book on Robert Venturi, John Rauch and Denise Scott Brown (2016, Park Books).

Sam Jacob Back to top

Being Revolutionary

There are times when, though full of enthusiasm and sentiment for a way of doing something, you are ill-equipped for the terrain. You need a map, a foothold at least, a push in the right direction. So it was with Learning From Las Vegas. Less a signpost and more a great big billboard advertising the richness of what one might call the pop vernacular. In its pages the authors’ enthusiasms for an architecture whose roots might be in the ordinary as much as the canon, the idea that sociology and semiotics might be as important to architecture as architecture, illuminated the landscape not only of Las Vegas but of all of the ordinary and unideal world that surrounds us. It showed that yes, this could be considered seriously – and sometimes humorously, too.

Re-reading Learning From Las Vegas now, there’s something else. Alongside its headline we read comments about race, about politics and policy, about environmental issues – ideas that are urgent today but which are still too often evaded in architectural thinking. The political sensibilities of Learning From Las Vegas (and VSBA as a whole, too) are usually ignored. But perhaps the thing that really resonated – and still does now – is how full of humanity a book about architecture could be. How broad in scope its way of thinking about the designed world could be. And how much of that thinking can happen by looking at what is already around us. As the authors write in the opening lines of their book, ‘Learning from the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary.’

That revolution is a contemporary project too. To give architecture ‘eyes that see’, complexities and contradictions rather than myopic tunnel vision, to embrace multiplicities of meanings, to give agency to the overlooked, the ignored, the oppressed and repressed. Learning from Las Vegas is not really about casinos and neon signs. Its still fresh urgency resides in how to challenge the power inherent in the edifices of architecture and the city, and even more, our own assumptions about what an architect could be.

Thank you, Denise, for taking Bob to Las Vegas in the first place. Thanks to both of you for showing us something of what you saw there. And thank you for showing us other ways of being architects. For showing us that architecture could – should – be about much more than architecture.

Sam Jacob makes work spanning scales and disciplines from urban design through architecture, design, art and curatorial projects.

Caroline James & Arielle Assouline-Lichten Back to top

Denise Scott Brown and Her Lasting Influence

In 1991, the Pritzker Prize was awarded to Robert Venturi, excluding Denise Scott Brown despite the pair’s equal partnership as VSBA. In the time that has passed since this act of flagrant sexism, Denise Scott Brown has been a sounding horn for the importance of inclusion, recognition and joint creativity in architecture.

To bring her message to a wider audience took the advocacy of the next generation. When we were students at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, we launched a global petition to demand that Denise’s contributions be recognised by the Pritzker Prize committee. The petition, signed by over 21,500 people, among them Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Farshid Moussavi and Venturi himself, reignited the controversy about equality in architecture and revealed the glaring need to shift the culture of awards, the culture of schools and the profession at large.

What can we learn from Denise as the field of architecture moves forward in a landscape that is becoming ever more attuned to some of the injustices it may have previously been complicit in?

For starters, she has always been political, speaking out about sensitive subjects, such as gender in architecture, well before the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, and her approach to design has always been collaborative and interdisciplinary. Growing up as an architect in the 1960s meant navigating a profession that she has likened to a boys’ club. Denise chose to speak up before others were courageous enough to do so – and when professionally it may have been less expeditious.

The first two words of one of her most famous works, Learning from Las Vegas, are the operative conditions. To be ‘learning from’ is an attitude of listening. To that end, Denise is a tireless listener and explorer of the built environment. To learn from something, rather than impose onto, is the key to her work and lasting influence. For many, she introduced to architecture the profoundly important act of listening, designing the built product through that deep awareness – and paying attention.

Her partnership with Robert Venturi, is also part of the strength of the work, rather than being a deterrence. She has described their partnership as a ping-pong of ideas, and the work is better for this interchange.

Our world in 2020 is more aware of the importance of collaboration and equal recognition. Denise’s legacy is being built in a time where she can finally enjoy the fruits of her labour. It’s a given that architecture needs to be inclusive, diverse and representative of the society it works for. To that end, her lasting legacy is her practising collaboration, and her demand – whether through her teaching, projects or words – that society embodies the values of fairness and justness that it purports to be.

Caroline James is an architect, writer and painter based in Boston. She is a founding board member of the Harvard Square Neighborhood Association for public participation in the built environment.

Arielle Assouline-Lichten is a designer, architect and advocate for women in design. She is the founder of Slash Objects, a design studio creating products and furniture based in New York.

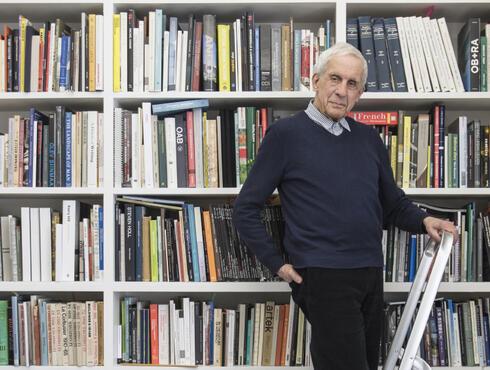

Header image credit: Photo Denise Scott Brown © the architect