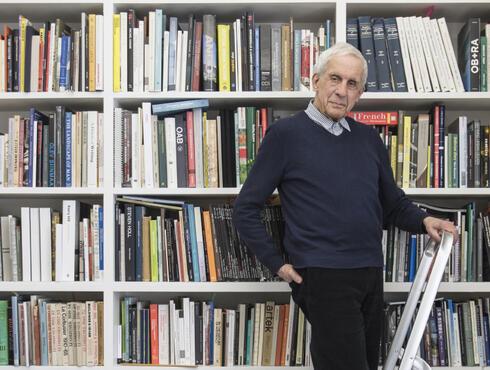

Each year the Soane Medal & Lecture is awarded to a practitioner, historian, educator or writer who has made a lasting contribution to the field of architecture. On the occasion of the 2017 medal, five different voices from architecture reflect on the work and legacy of Rafael Moneo.

Stan Allen Back to top

Learning from Moneo

In 1984, nine years after the death of Franco, as the Spanish cultural scene was sparking into life, I was fortunate to spend a year in Madrid working for Rafael Moneo. I learned many things from Moneo, not the least of which was never to imitate his formal choices. Moneo insists on taking every project on its own terms, and rarely repeats; he is a relentless critic of his own work, constantly editing and revising. He would never impose a ‘signature’ style on a building for the sake of consistency. I often tell my students that the iterative character of design requires that the architect embrace a paradoxical mindset, a thought which also has its origins in my experience with Moneo. In other words, to drive a design project forward, at any given moment you have to be entirely convinced that your solution is the right one. It takes time and effort to draw up a project, and you can’t do that without belief in the solution. But the moment you see its form, its intent and its contours, you have to be ready, without regret, to revise and rethink – up to and including starting over from scratch, something I saw Moneo do countless times.

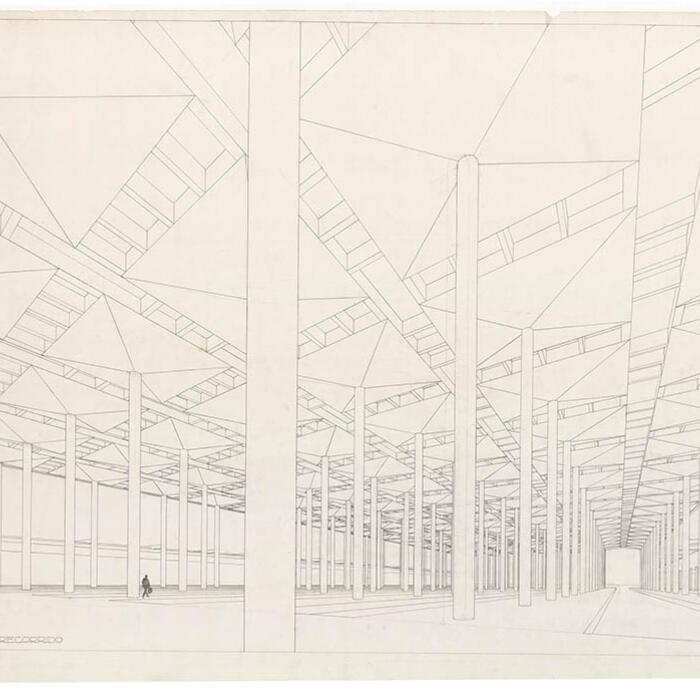

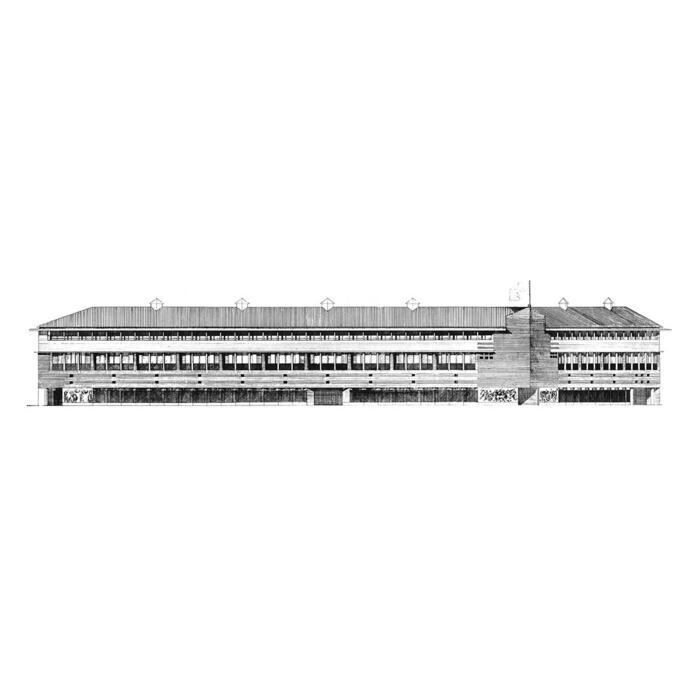

As much as I learned from Moneo, I also learned from the other young architects in the office. I learned not to overwork a drawing – freshness and immediacy were the qualities sought after, which demanded concentration, efficiency and a sense of knowing when a drawing was complete. I gained a respect for the depth and richness of architectural history. I was introduced to architects such as Ignazio Gardella and Luigi Moretti, who had their own way of working with history. I learned about building and materials. There is a certain quality to the drawings produced in Moneo’s studio that always anticipates their realisation as construction: there are few blank surfaces; brick coursing is always hatched, concrete stippled, and each joint and material transition is notated. Paving is always indicated in plan drawings.

Intellectually Moneo is also, for me, a model of a thoughtful architect who uses writing to reflect on his practice, and is always generous (although rigorously critical) in assessing the work of his peers. My speculations around the idea of ‘field conditions’ can be traced back to the Mosque at Cordoba, which I first visited with Moneo on the way to a building site. The essay ‘Infrastructural Urbanism’, which argues for the agency of a hybrid architecture/engineering approach to urbanism and public space, owes a debt to the Atocha Station in Madrid, the first project I worked on in the office.

Another piece of advice I give to my students – particularly when they seemed to be bogged down with a project – is to ‘work less and produce more’. It’s not something Moneo ever said, but an idea absorbed in the atmosphere of his studio. What I mean by this is that you work best in short intense bursts of concentrated productivity. In his studio, Moneo would go from desk to desk, making corrections, and asking each one in turn, ‘but why isn’t it finished yet?’ (Often, it seemed, minutes after you had started a drawing.) Design is a process of accumulating information about a building that exists only in the imagination. In order to achieve the density of the real that Moneo looks for in his architecture, you have to build up many layers, and look at a project from all angles, understanding exactly what each drawing was intended to convey and communicating that information with a minimum of elaboration. Making architecture is a long and often difficult process; it requires patience but also passion and commitment. When you see Moneo at work, you understand that he loves architecture. It fascinates him endlessly and gives him pleasure. Sometimes we forget that this is what it is all about.

Stan Allen is an architect working in New York and Professor of Architecture at Princeton University. His most recent book is Situated Objects (2020, Park Books).

Ricardo Flores & Eva Prats Back to top

To be Part of the Whole

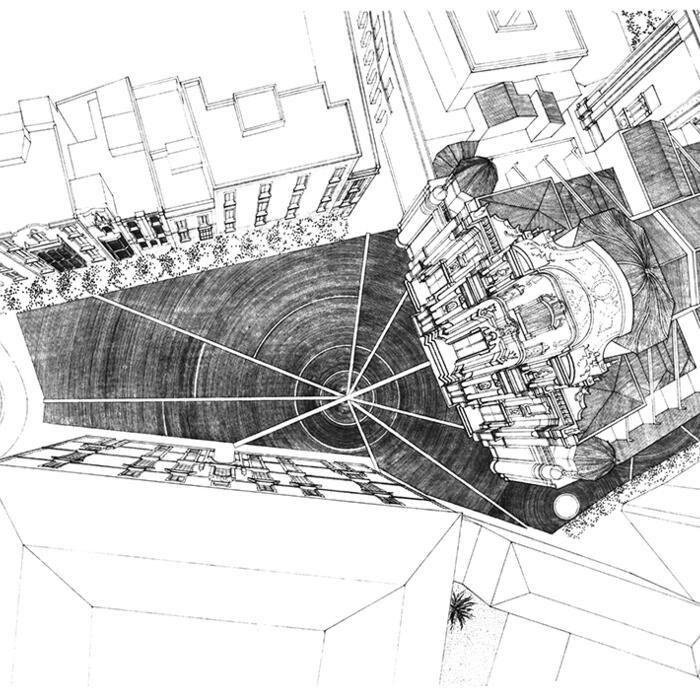

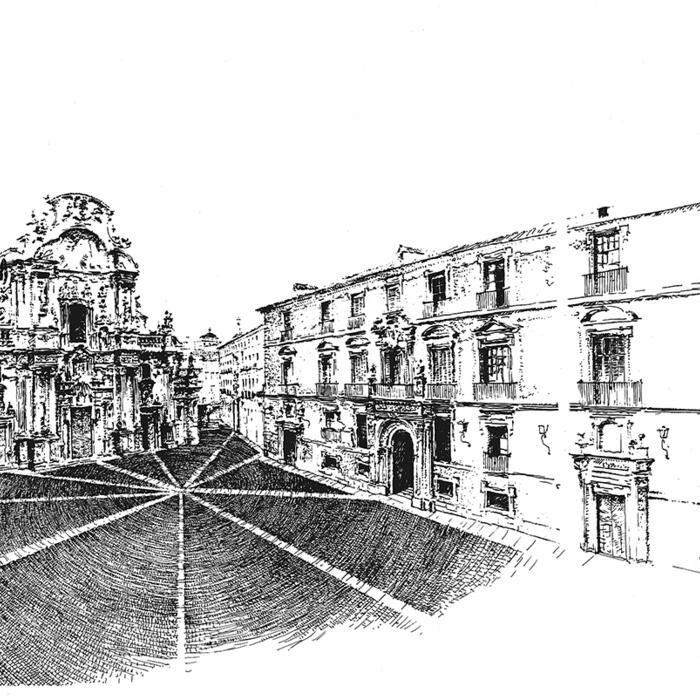

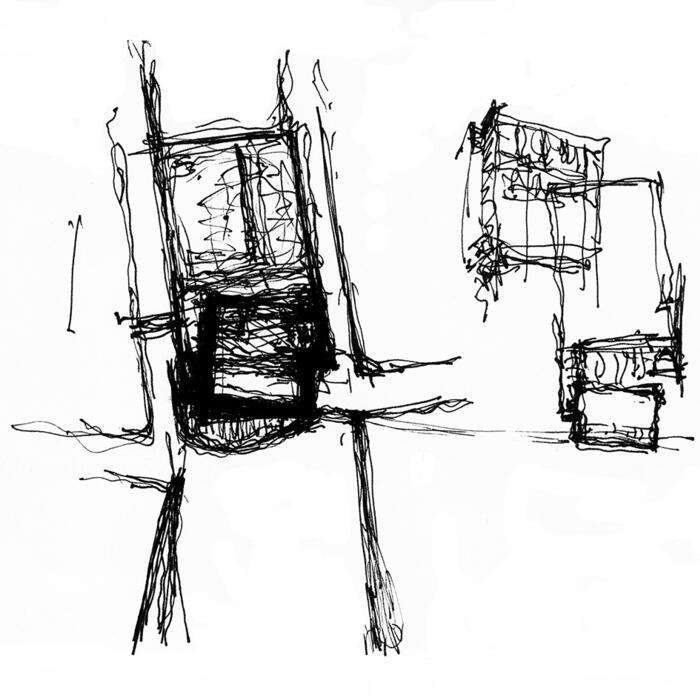

For Rafael Moneo, hand drawing is a driving force to think further, something present in all stages of his projects: in the initial sketches, quick drawings that catch and fix first intuitions, or in his plans, which allow us to visit the work through them. To look at these plans is to walk through his architecture and the succession of connected scenes. The hand with the pencil has travelled through these same spaces back and forth hundreds of times before us, until the articulation between them is so intense and at the same time so simple that the passage from one to the other becomes both natural and surprising at the same time.

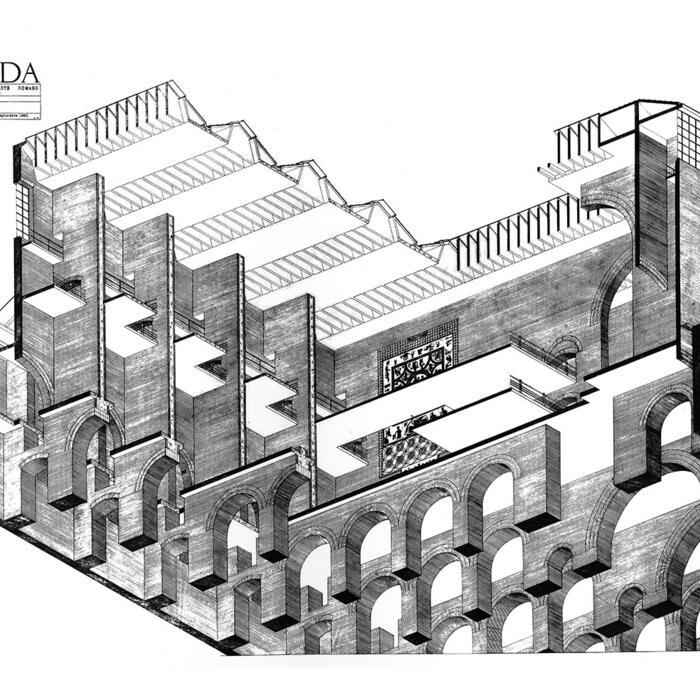

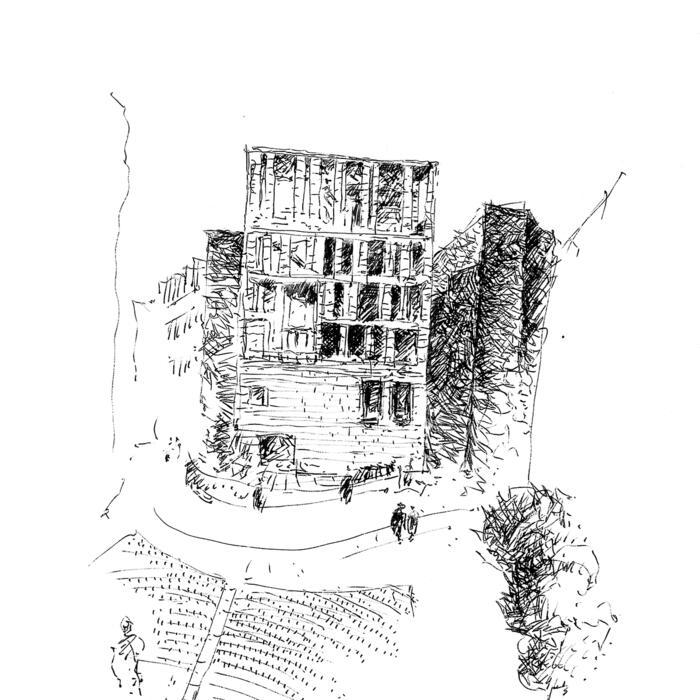

But above all, the axonometric drawings are the ones which trap us: always from a different point of view, it seems that the architect has asked the project: how do you want to appear? Axonometric drawings such as the Murcia City Council extension immerse the observer instantly in a world from which it is very difficult to get out. The project disappears into the immensity of the drawing, and that is precisely what the building wants: to be part of a square and a church, of pavements, windows and cornices and the entirety of Murcia and its surroundings. Everything, city and squares, are contained within it.

These drawings, capable of expressing so many things, are a kind of language for a conversation. One can read in them different stories related to our own personal experiences, and they become interesting objects between the people and the subjects, allowing for a conversation. In the studios of the architecture schools, Rafael Moneo’s drawings, like those of other masters who float over the classes, become these objects about which one can discuss, they always help us to exchange.

Ricardo Flores and Eva Prats founded Flores & Prats in Barcelona in 1998, a studio that combines design and construction practice with an intense academic activity.

Emilio Tuñón Back to top

Solamente una Vez

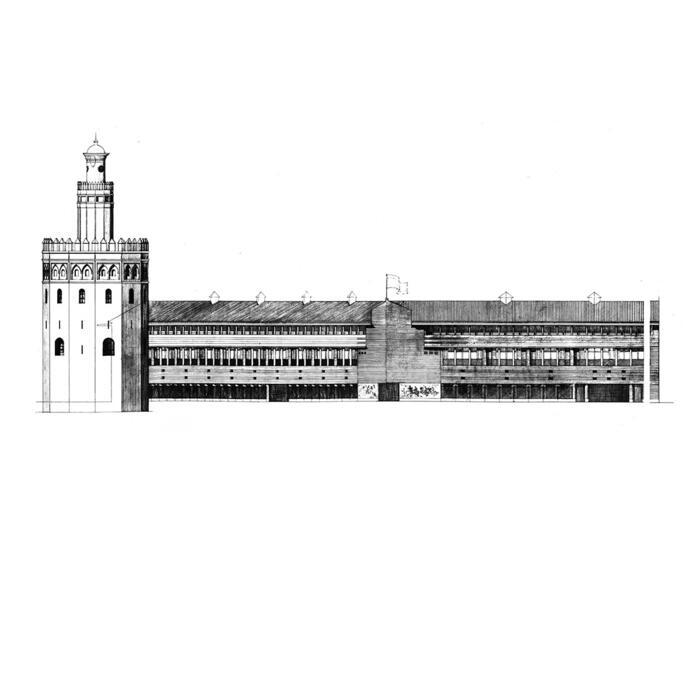

I remember with a certain feeling of nostalgia that month of August 1982, when I joined Rafael Moneo’s office as a collaborator. Rafael was sketching the first drawings for the building of the Previsión Española in Seville. With well-sharpened pencils he stroked the surface of a thin vegetable paper, accurately designing the building’s facade while whispering a well-known bolero composed by Agustín Lara for a friend who decided to join a religious order. I have spent years recalling the exciting first moments in Moneo’s office, during that hot month, in which Rafael recommended that we learn ‘to see the world through the eyes of architecture’. But above all I remember Rafael, absolutely relaxed and drawing, and at the same time singing this bolero – itself a beautiful song that spoke to a total dedication.

Memory is capricious. Sometimes it fixes scenes and events in our head that, being inconsequential to others, can shape the way we understand the world. Over the years, this almost domestic image has been fixed in my own memory as a kind of initiatory moment for me as an architect. Over time this vision of the master, slowly sliding his pencil across the paper, has come to be a kind of allegory for me, in its staging of the dedication that architecture requires. This dedication is, without doubt, present in the committed and honest attitude that Rafael Moneo has always maintained with architecture. In my memory, when Rafael was drawing that facade and whispering those verses, he was making present his interests as an architect. These interests have always been characterised by a permanent oscillation between an architecture connected to the intellectual concerns of the world and an architecture in intimate contact with reality. And it is precisely this way of understanding architecture, of approaching the discipline, which has served as a model for several generations of Spanish architects, opening the doors to a generous way of understanding architecture, and by extension, opening the doors to a committed way of understanding the world.

Emilio Tuñón Álvarez is a Spanish architect. His practice, Mansilla + Tuñón Architects received the 2014 Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts from the Spanish Ministry of Culture. He worked with Rafael Moneo from 1982–92.

Mark Lee Back to top

Rafael Moneo at Harvard (from Tange to Gropius and Back Again)

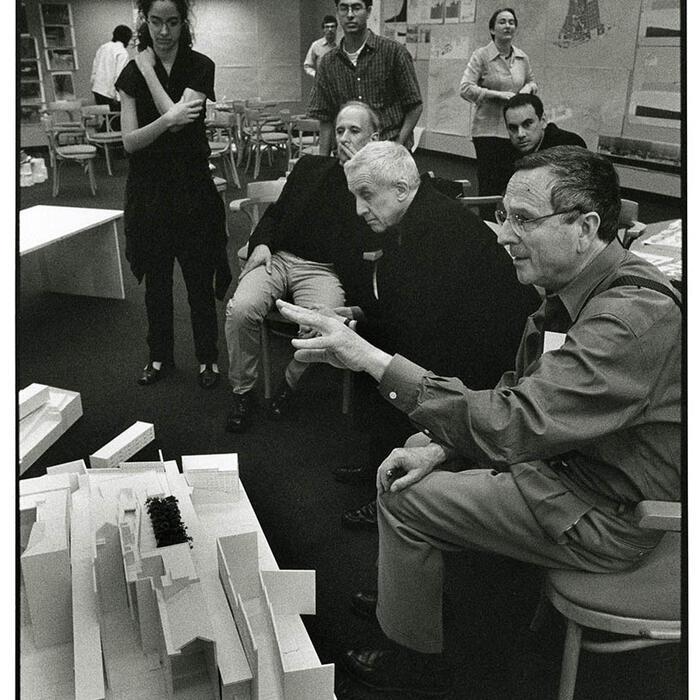

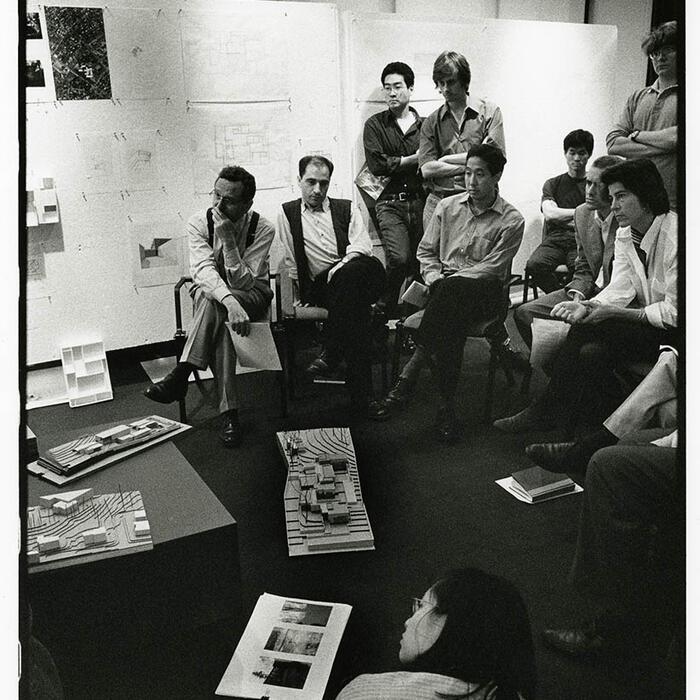

When Rafael Moneo was appointed as Chairman of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1985, he delivered the inaugural Kenzo Tange Lecture titled ‘The Solitude of Buildings’. Delivered at a time when American architectural education was entrenched in debates about theory versus concerns for practice, the Tange Lecture posited building construction as a foundation from which theoretical concepts could be generated. Already a significant practitioner and a respected figure in theoretical discourse, Moneo charted the course of his forthcoming chairmanship at Harvard in bridging the division between theory and practice.

Five years later, upon the completion of his term as Chairman in 1990, Moneo delivered the Walter Gropius lecture titled ‘Reflecting on Two Concert Halls: Gehry vs Venturi’. The lecture considered two American projects – one that was eventually built with significant alterations and the other never built – as lenses to view the global state of architecture. Observing the waning cultural importance of architecture in relation to ephemeral media, Moneo questioned the fundamental necessity of architecture and the subsequent role history plays in our society.

The two endowed lectures that marked the tenure of Moneo’s chairmanship at Harvard were, coincidentally, named after two architects who wrestled with the role of history in their respective pursuit of modern architecture. Separated in age by thirty years, Walter Gropius (1883) famously tried to abolish the history of architecture course at Harvard as a platform for a positivist project, while Kenzo Tange (1913) strove to integrate traditional typologies and motifs with modernism in his search for a national identity in postwar Japan.

These disparate positions occupied by Gropius and Tange encapsulate a significant tension between the burdens of history and the imperatives for progress that permeated Moneo’s teachings. The belief that architecture should always be situated between theory and practice, and its inevitability as a historical project is an important lesson I learned from Moneo as a student. It is a principle that I continue to espouse, and one I continue to model for aspiring architects.

Mark Lee is the Chairman of the Department of Architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design and a partner in the Los Angeles and Boston-based office Johnston Marklee.

Peter Eisenman Back to top

Moment of Clarity

It is not very often that one witnesses, or even participates in, a life changing event. However, that happened to me while I was with my friend Rafael Moneo. It was in Venice, in the summer of 1985. I had just finished a three-year stint teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design at the invitation of Harry Cobb, then chairman of architecture. All three of us, Cobb, Moneo, and I, happened to be in Venice at the same time. Cobb, who was looking for his successor at Harvard, had provisionally offered the position to Moneo. Moneo found me and said we needed to talk. So we set off on a long, rambling, slow walk through Venice, with no particular destination in mind. As we walked and walked in the mid-afternoon heat, Moneo talked continuously. He talked about architecture, his work, his family, his life in Madrid, but he always returned to the subject of his future, which Cobb’s invitation had made so urgent. At a certain moment, Moneo abruptly stopped and turned to face me. Almost shaking, he asked, ‘What shall I do about Harvard?’ And then immediately he made a self-aware statement of enormous clarity: ‘Peter,’ he said, ‘I want to be a world architect not just an Iberian one!’

The rest, as they say, is history: the distinguished international career, as both practitioner and teacher, of a great world architect.

Peter Eisenman is principal of Eisenman Architects. His career has combined the work of practice and the completion of numerous projects with academic appointments, including Yale University, where he currently teaches, as well as Cambridge University, Harvard University, Princeton University, Ohio State University and the Cooper Union. In 2020 he was awarded the Gold Medal for Architecture by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Header image credit: Photo Michael Moran, courtesy Rafael Moneo Arquitecto