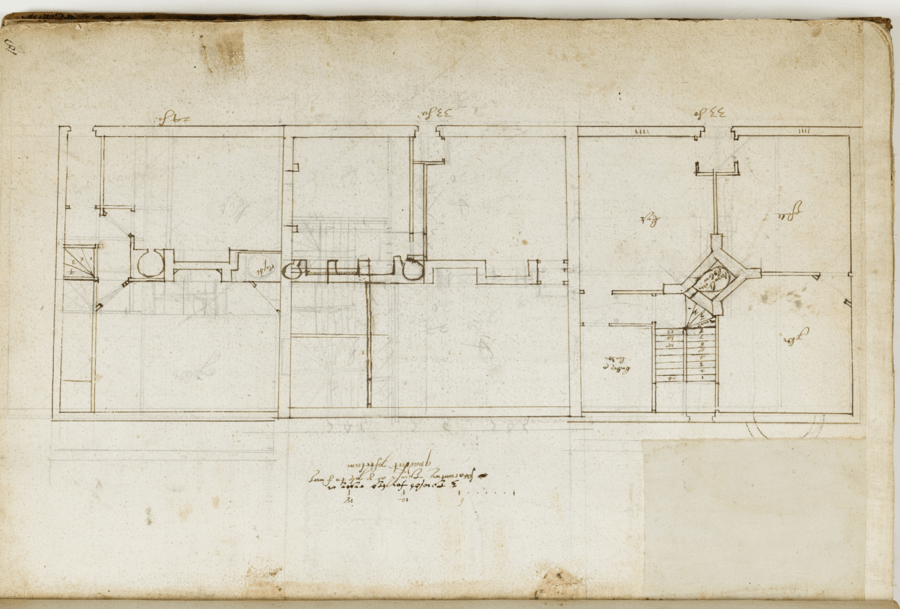

John Thorpe

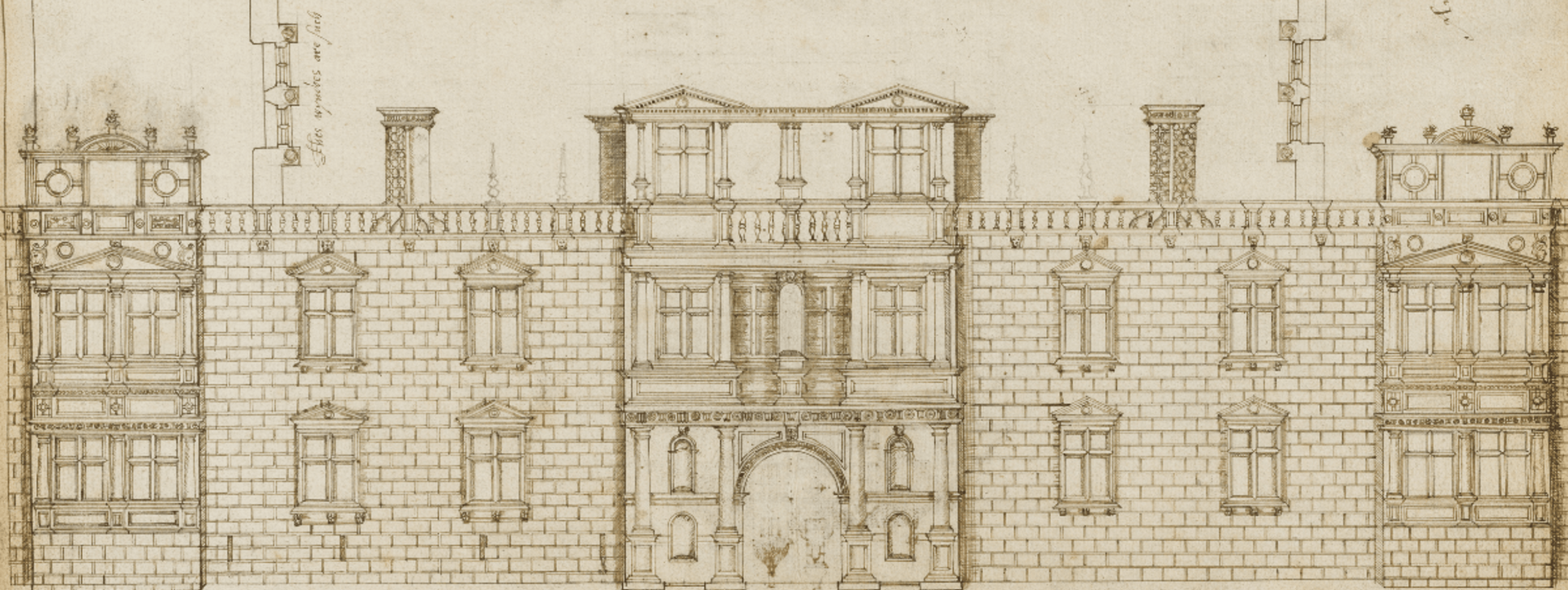

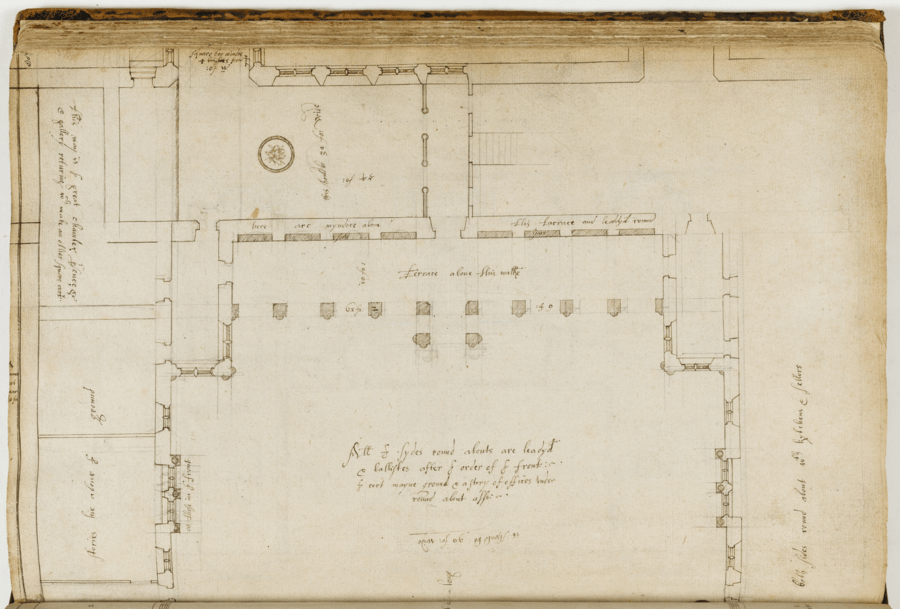

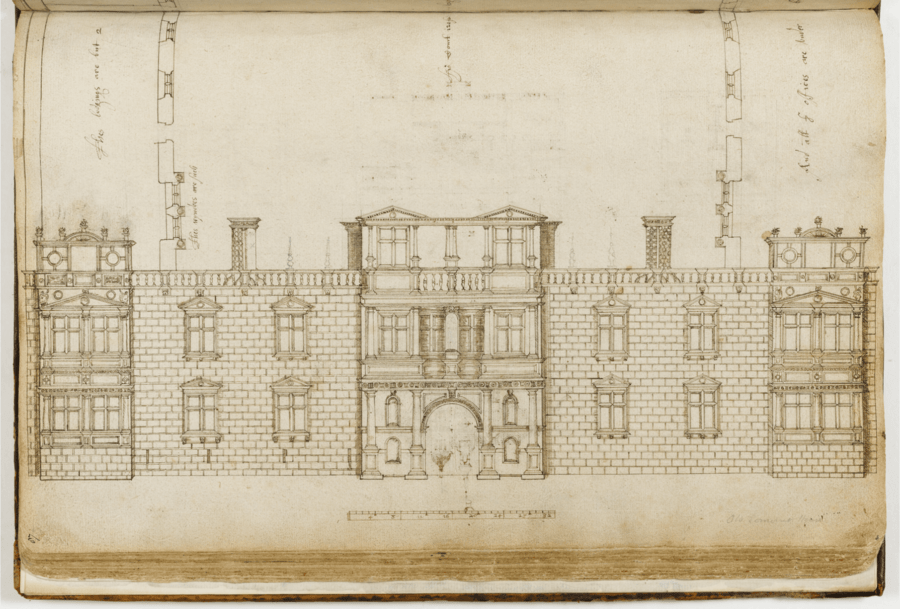

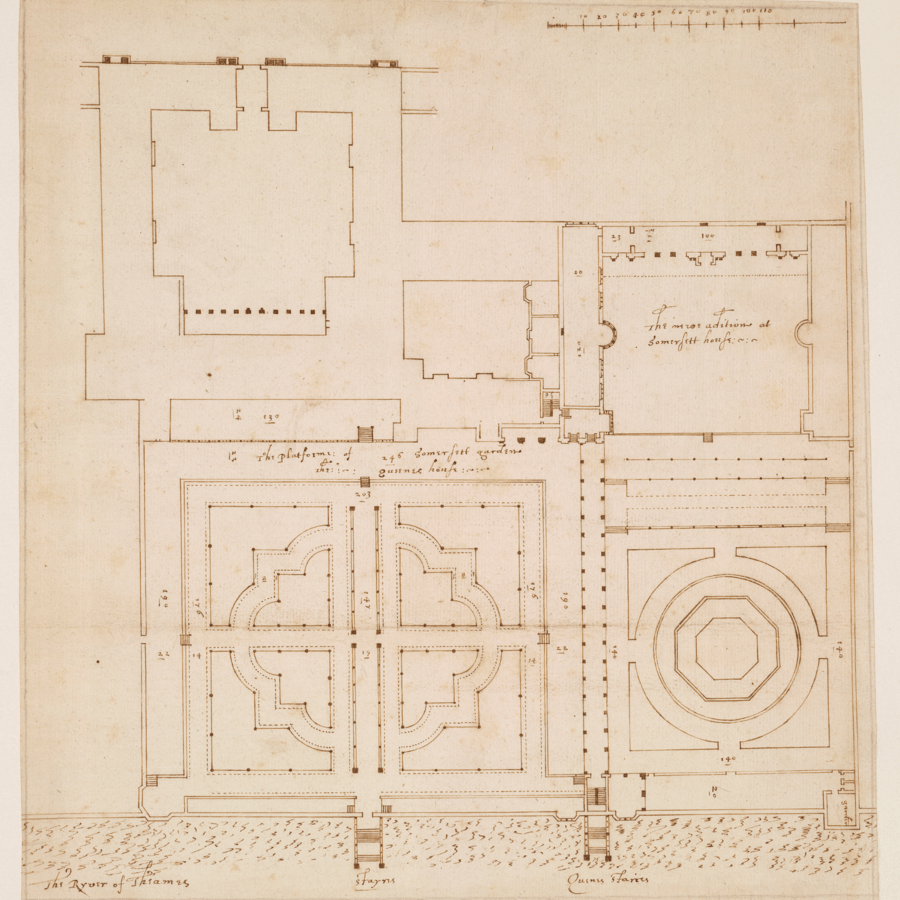

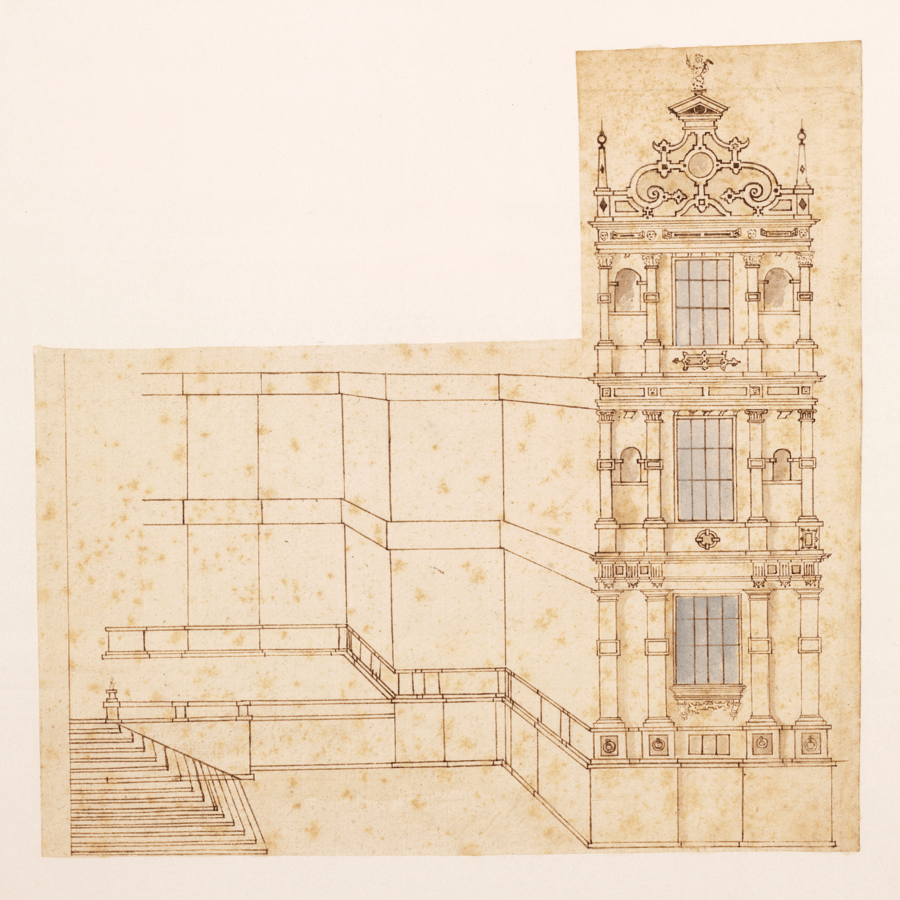

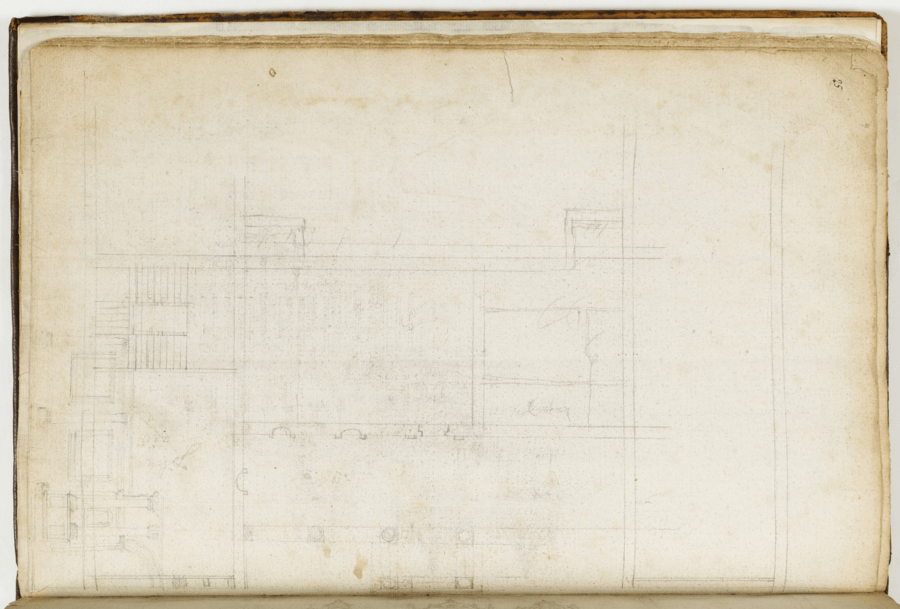

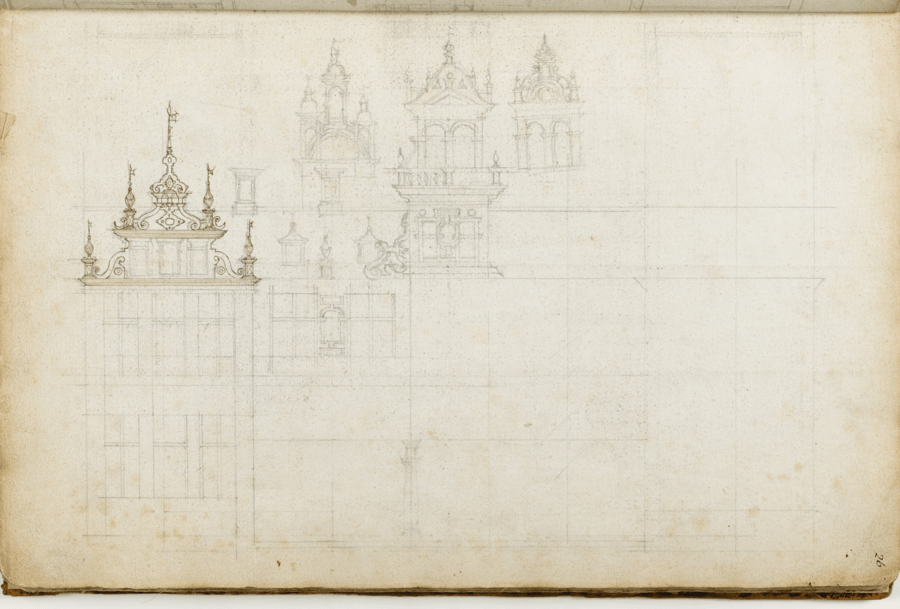

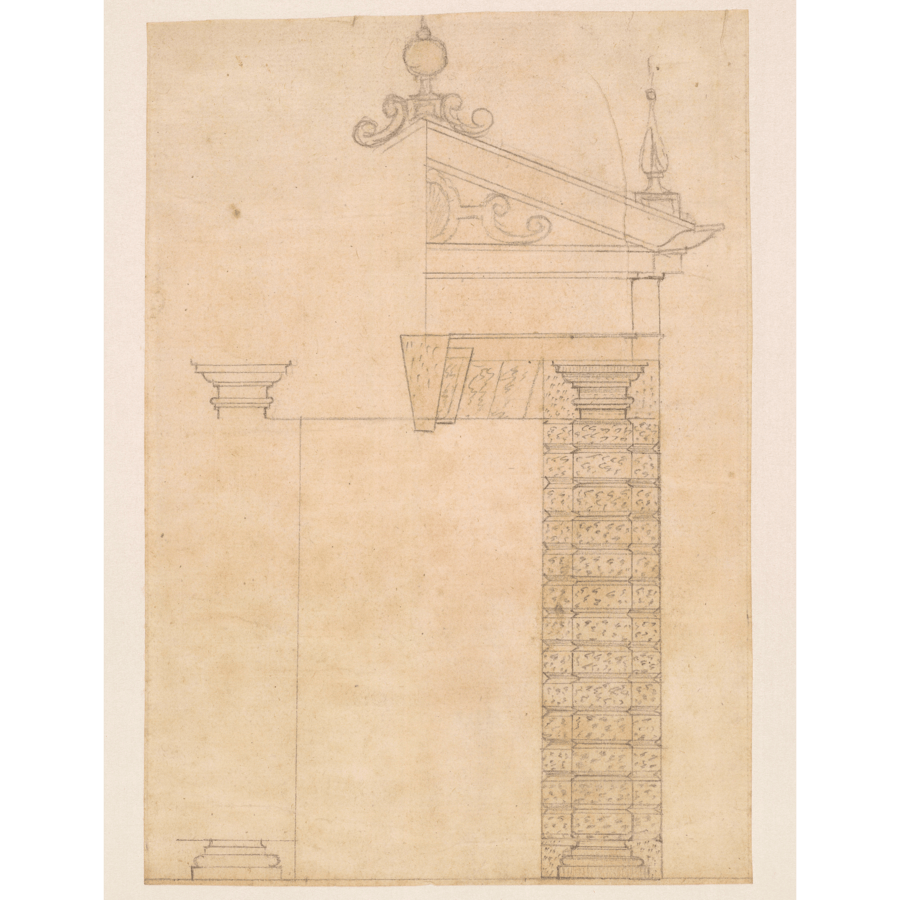

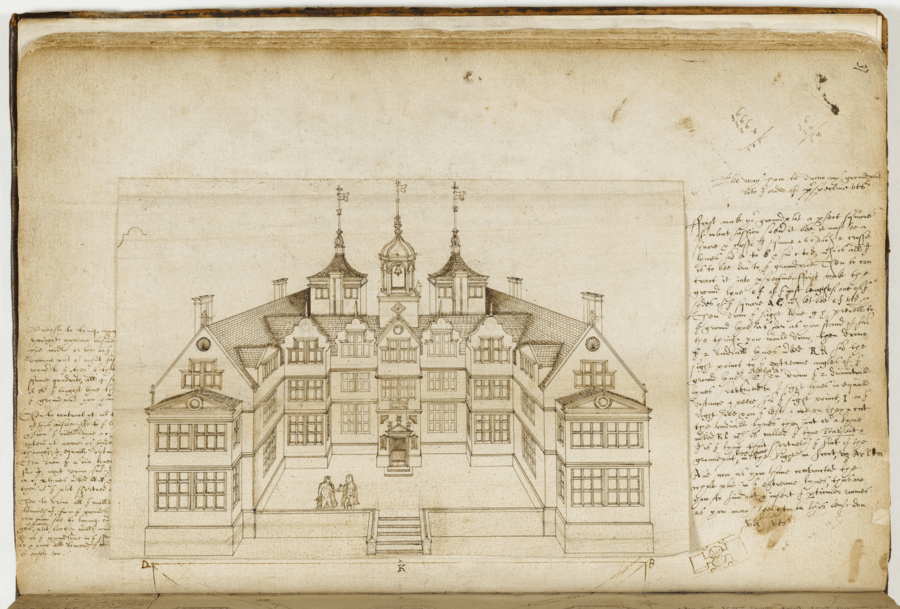

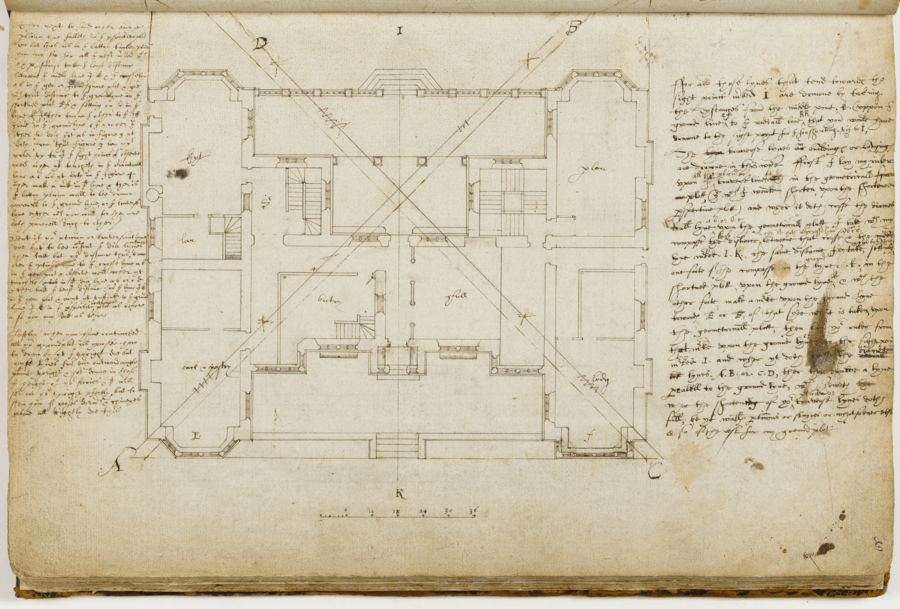

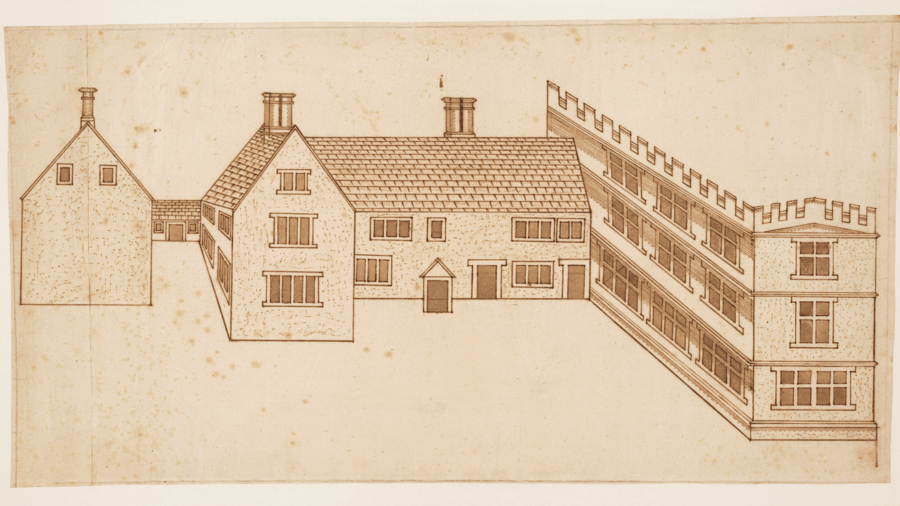

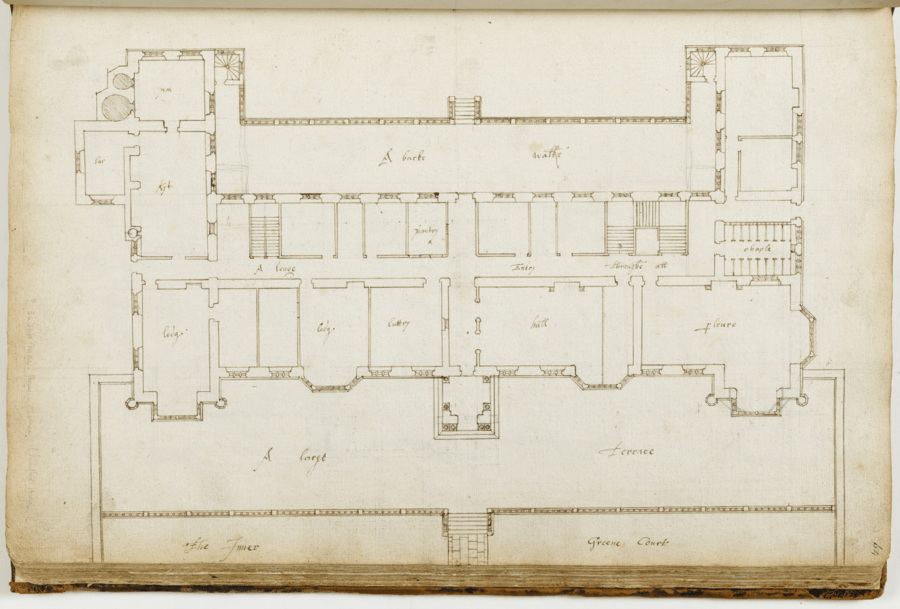

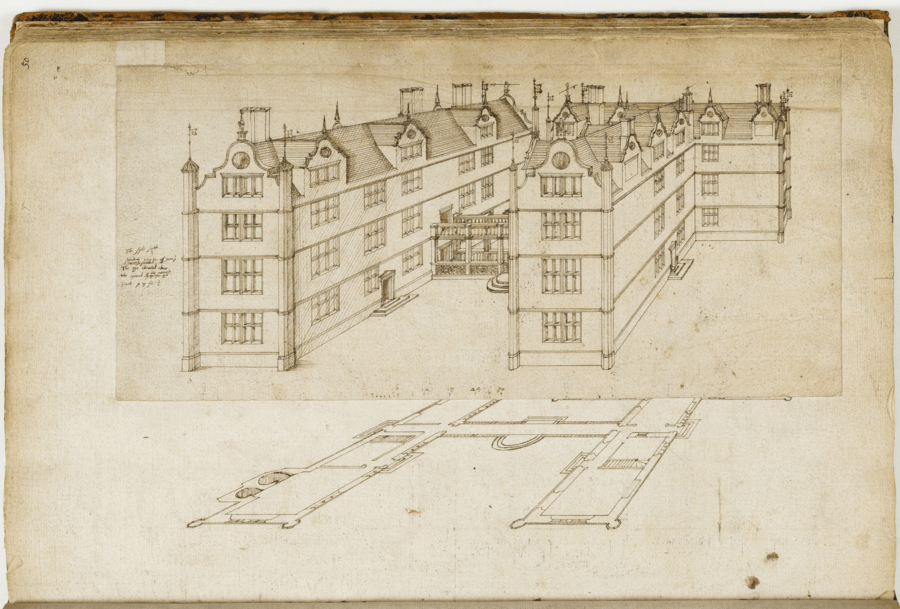

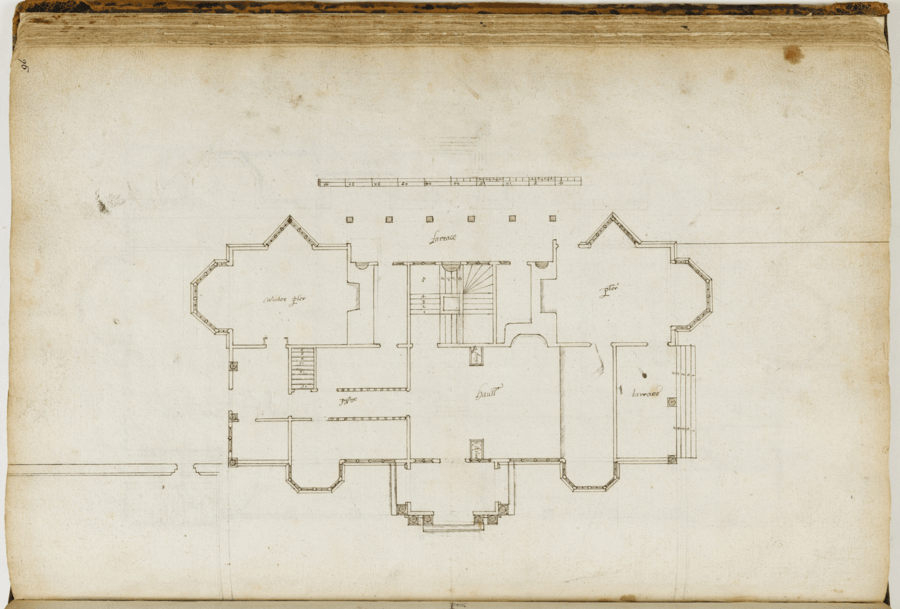

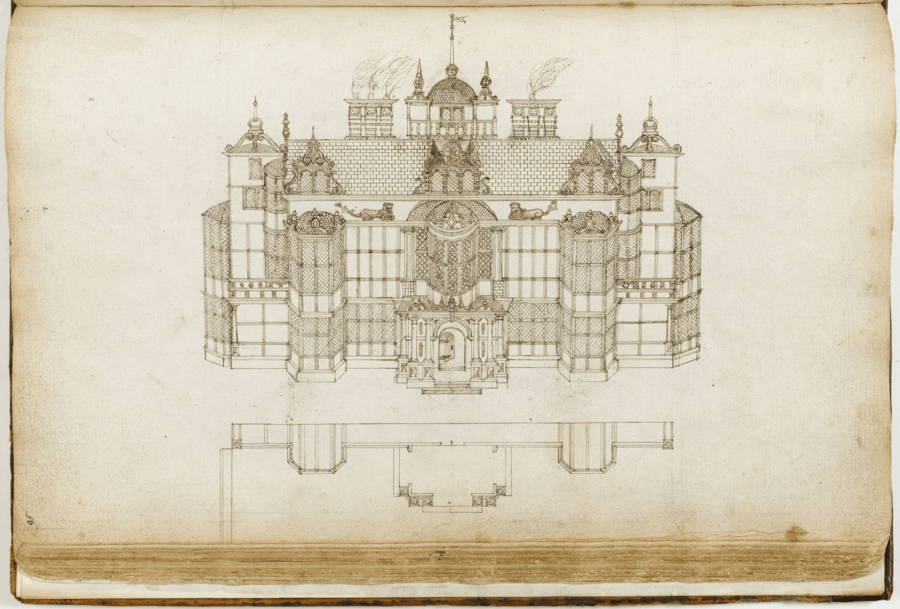

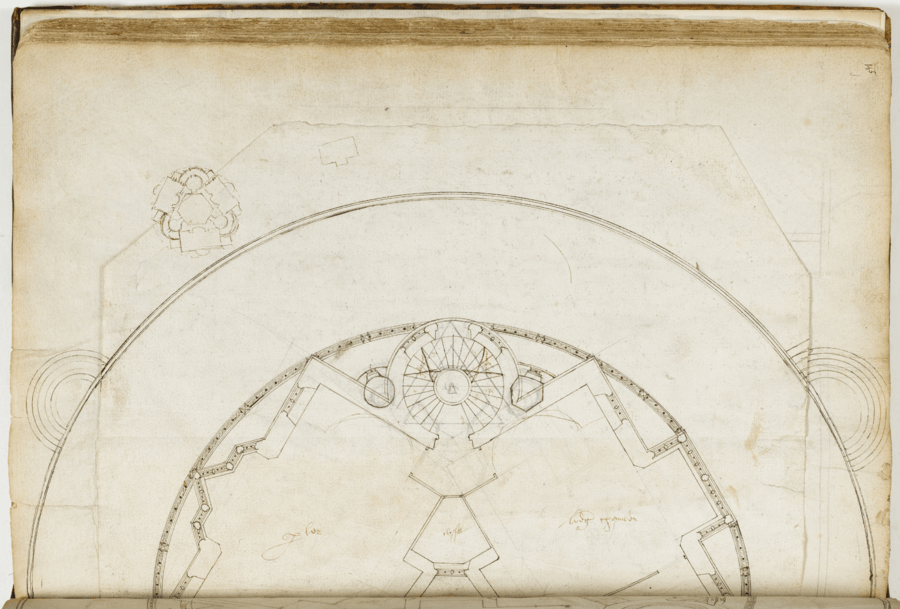

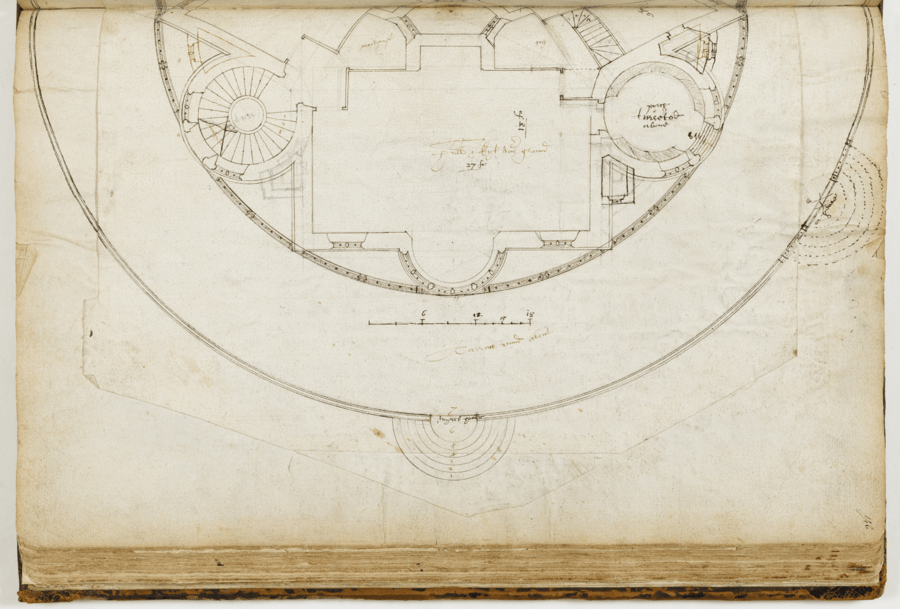

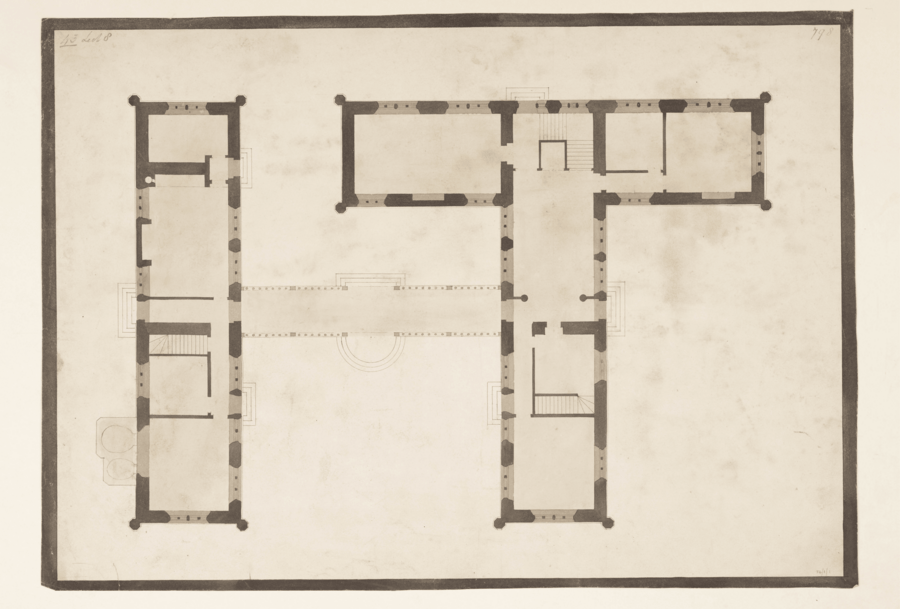

Survey drawing of ground floor and main elevation of Somerset House, Strand, London, with proposed alterations, c.1603,

Brown ink and pencil on laid paper, 425x272 mm

SM Volume 101/87-88

This drawing shows two things at once: three sides of the main quadrangle and the iconic elevation of Somerset House, the most important of the so-called Strand palaces in London, built by Edward Seymour, Lord Protector Somerset, between 1547 and 1552. It is a working survey which includes proposed alterations, and information about the upper floors, as is typical of most of Thorpe’s drawings. The style of this elevation, an eclectic combination of Continental and traditional features, epitomises the mixed influences of the English Renaissance.

For more information see here.