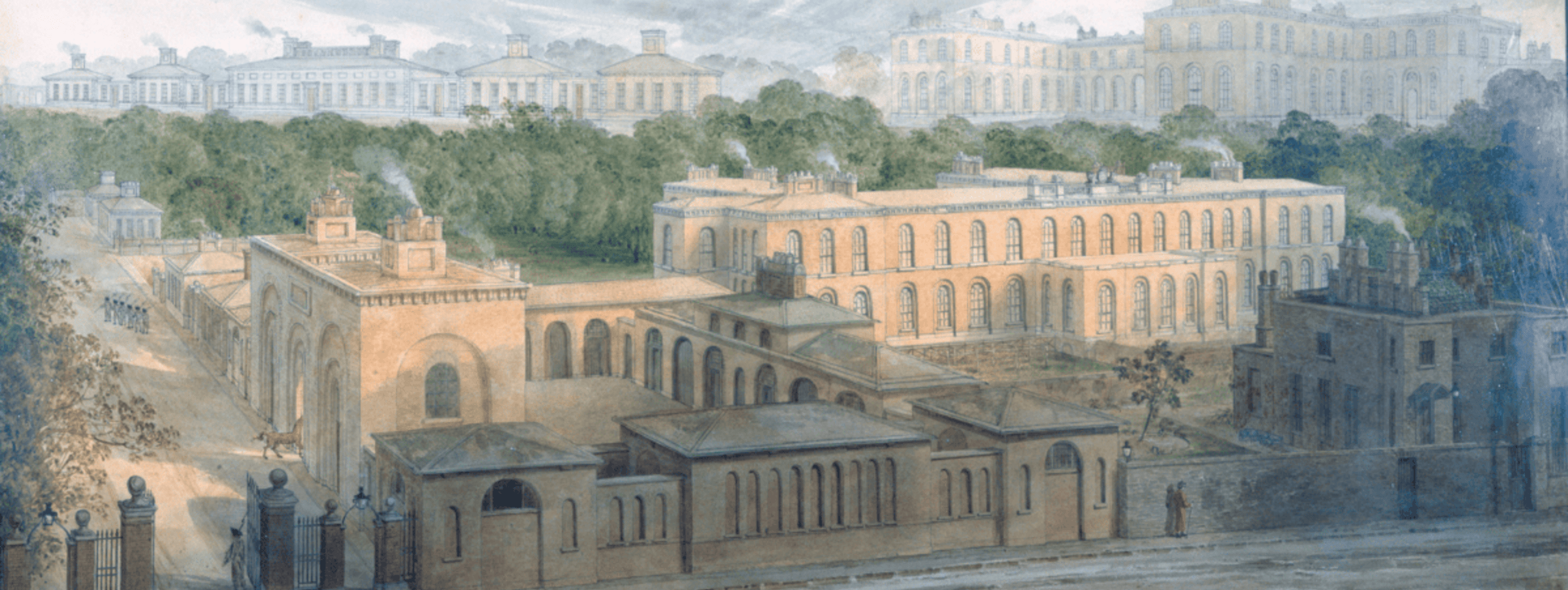

Above: Soane Office, Composite perspective of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea in the form of a bird’s-eye view of the Infirmary and additions, 1809-15, 1818

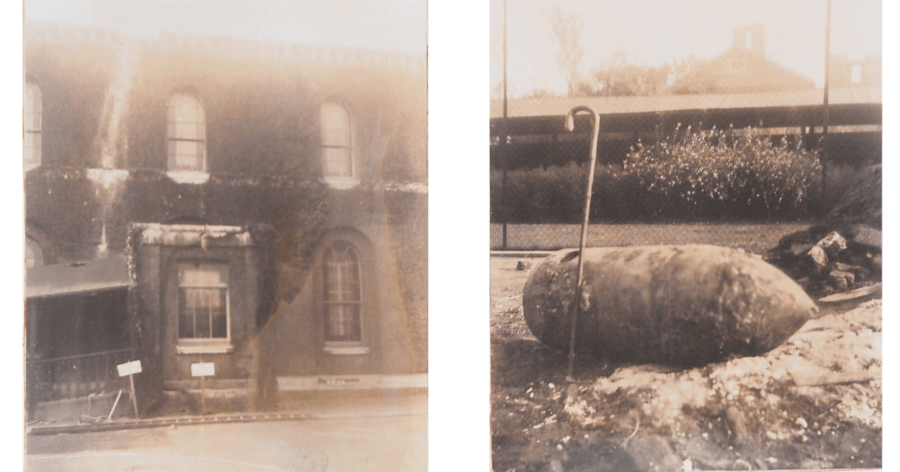

Soane was commissioned to build a new infirmary as part of a more general redevelopment of the Western edge of the Royal Hospital’s estate, with the Soane buildings including a new Stable Yard, built on the site of Wren’s original stable yard. A workshop, or Artificers’ Yard, was also included in the redevelopment, on the site of the old coal yard, with the workshops built around a slight hollow in the ground. This localised geographical feature would play an important part during the London Blitz.

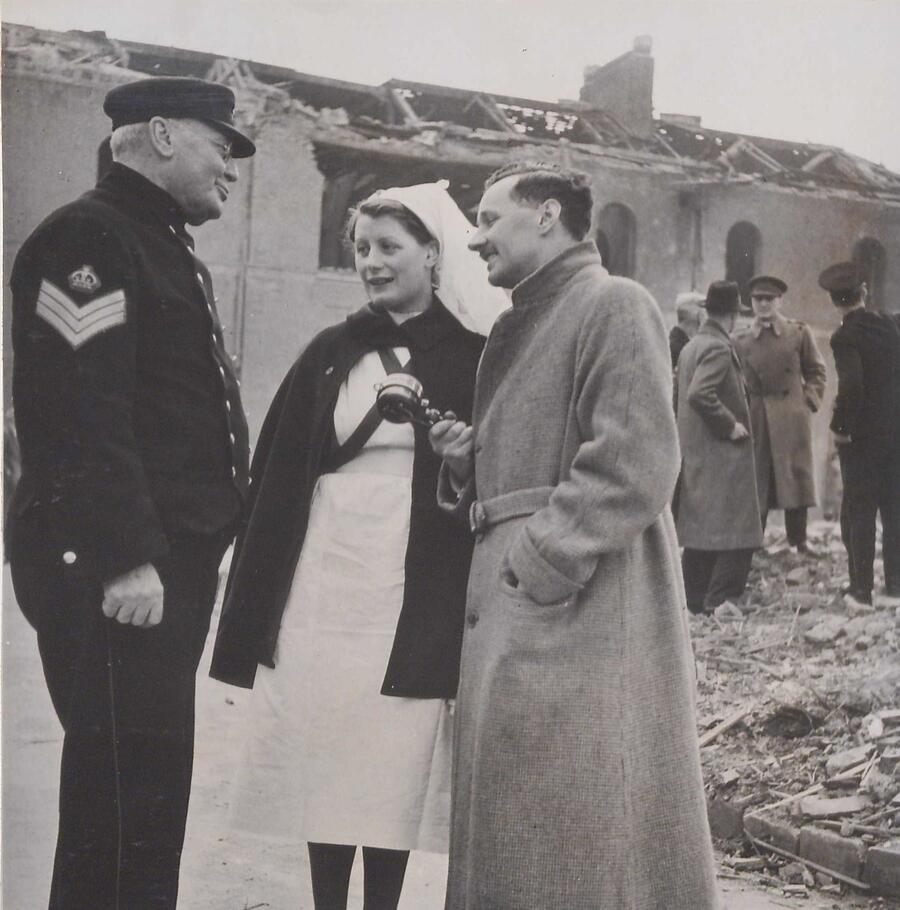

In 1938 as war clouds once again formed over Europe, plans were agreed for evacuating the ‘whole establishment’ of around 500 Chelsea Pensioners, to a place of safety outside London in the event of an emergency. Unfortunately, a combination of toxic politics and complex logistics meant these plans were never implemented. The Commissioners did however agree the terms of a private arrangement with a retired army officer, Major Walter Morland for around 50 patients from the Soane Infirmary to be surreptitiously spirited out of London on the eve of war in September 1939, to stay at Rudhall, Major Morland’s country house near Ross-on-Wye in Herefordshire. Rudhall would remain a Royal Hospital out-station for the duration of the war.