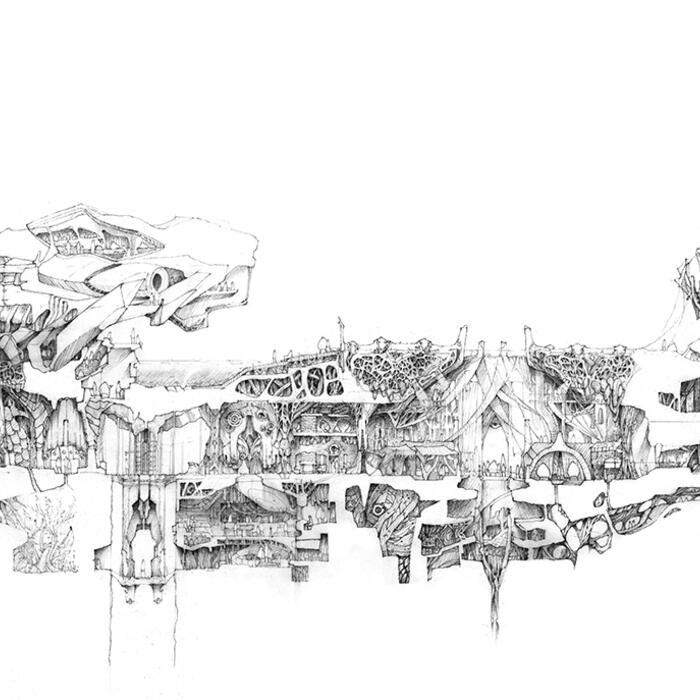

Marc Brousse, L'horizon d'une ligne s'eloigne

Shortlisted entrants to the Architecture Drawing Prize are interviewed by members of the Soane Museum Youth Panel.

Marc Brousse Back to top

The following text is an interview between Viola Turrell of the Soane Museum Youth Panel and Marc Brousse.

VT: What is your greatest source of inspiration?

MB: I am fascinated by the art of building – from ancient times to the present. For decades, civilisations arose from urban and architectural cultures. Utopian architecture has been dreamt to express an escape from history, to give a moral vision of the world; the representation in the architectural realm is relevant to represent these notions.

I have developed my singular style from the research I have conducted into the history of the line, several architecture treaties from the Renaissance to the present and the notion of ‘parti et poché’ to represent architecture.

I have also been influenced by various artists such as François Schuiten, who has the ability to generate cities with intriguing architecture; M.C. Escher and his work on curved and cylindrical perspectives; Giorgio de Chirico with his metaphysical principles and his ability to recondition our time-thinking; and Jean-Jacques Lequeu or Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s pictorial and fictitious representations.

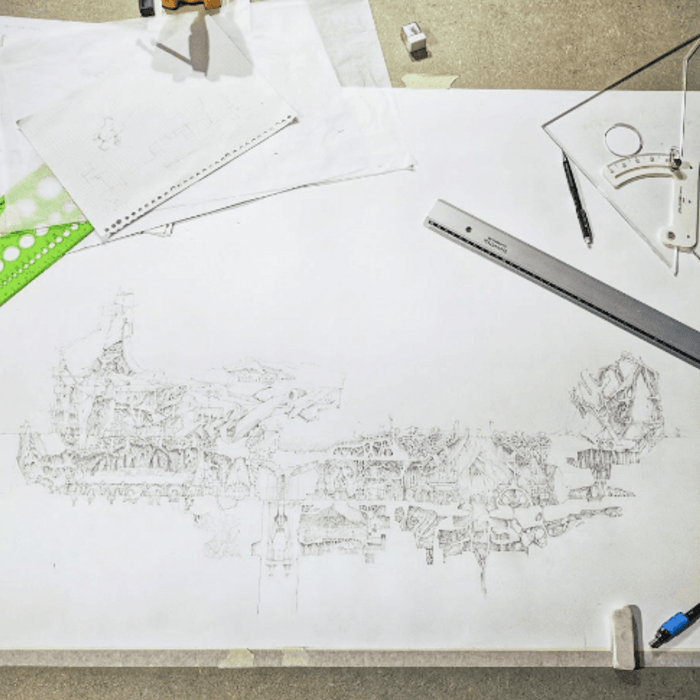

VT: What is the primary focus of your drawing?

MB: Throughout my art and architectural research, I developed my urban poetry ‘traitillism’ technique, which permits me to interweave figurative and abstract styles to express both the infinite and infinitely small. I believe the line symbolises life, space, thought and memory. Thus, I capture nature and architecture’s rhythm, allowing me to represent a specific vision of space and the world, changing our way of thinking about cities and the environments that compose us.

During my travels, I observed the various dialogues between nature and architecture: the urban scar upon nature and also the taming of nature by man. Moreover, I consider the epigenetic principle which states that development is the outcome of behaviour and environment; I apply this concept to urban development. Globally, the founding principles of civilisations are done through urban cultures nourished by symbols and utopias to engrave identity and generate the memory of places. Therefore, I tend to reveal through my drawings the fundamental values of our environment.

VT: How do you consider human interaction/usage within your space?

MB: I develop drawings according to different series or collections to formulate allegories between man, nature and architectural creation. These include:

- Revealing the intimate link between the architecture of man and nature. Every city is a unique species, a living organism formulated of different strata and rhythms, in the sense that the juxtaposition between buildings and spaces constitute the epigenetic programme for that place. As a developmental principle, epigenesis means that buildings do not merely echo the existing milieu but add something new and dynamic to the urban context. And the way in which people dwell in the city implements this epigenetic programme.

- Questioning the position of man within the city as a global, abstract and even elusive identity. Urban artefacts allow us to observe the relationship and scale of man in its context, a language he creates, generated through principles of complexity and contradiction architecture, composed with proportion he defines or characteristics issued by nature such as the Fibonacci sequence for example.

- Looking at the collection ‘gazing the crossroads of civilisation’ reveals, on one side, the soul of the city as an ultimate man-made expression of holistic principles. Through a dialogue between the architecture of man and nature, my drawings question the position of man within the city as a global, abstract and even elusive identity.

VT: What's most important to you when you design architecture?

MB: As the poet Chawki Abdelamir once said, ‘when time stops it becomes location’.

Architectural drawing has to express a spatial configuration to formulate a message, an emotion, an atmosphere, a place with memory and identity. I try to interweave the ‘traitillism’ technique with architectural codes and subjects I want to develop to generate a strong narrative drawing with which people can appropriate and interact.

Our memory, combined with the art of building, spatial experience and our capacity to take ownership of spaces, is defined according to the mounting of architectural artefacts and fragments of the environment because we define them as spaces of historic, scientific or even emotional interest – a space that is important for something, as opposed to everything.

I try to create a go-between: a hyphen between history, my architectural vision, and your eye and grey matter. I do this in order to imprint fragments of territories in your memory and stir emotions in the observation and the interaction with these illustrated places.

VT: Finally, a word of advice to aspiring architects?

MB: Like artists, I think it is relevant for architects to know and acknowledge the past as a tool to express modernity.

We often forget that urban development is part of the natural environment and not the contrary. Nowadays, nature is considered a tool, an ingredient, to formulate ‘sustainable’ architecture. We should reconsider how the natural grid can organise urban settings and redefine the way in which we dwell in cities.

Finally, I think it is a shame that most of the architecture we produce nowadays largely does not take into account the notion of harmonic rules and proportion relating to nature’s characteristics, such as those that enabled us to develop major architectural styles like the Gothic, Renaissance and Art Nouveau.

Matthew Poon Back to top

The following text is an interview between Viola Turrell of the Soane Museum Youth Panel and Matthew Poon.

VT: What is your greatest source of inspiration?

MP: Generally, I would look for things I find interesting in other disciplines, such as movie sets, animations, concept arts and sculptures.

However, for this specific drawing, I've avoided looking for inspiration from similar artists, but to channel my own aesthetics and imagination.

VT: What is the primary focus of your drawing?

MP: My primary focus is to reveal my own ‘world’, with creations that live and breathe in it. The question I asked myself was ‘How would my construct look if I were to follow my logic and desires?’ Hopefully, the result is something mind-blowing and unique.

VT: How do you consider human interaction/usage within your space?

MP: That's a tricky one! I figured that out by imagining the spaces with my eyes closed, as though I'm standing right there and looking around. I also thought of how the narrative goes in each pocket of space and how wild can they be in my world. As you can tell by zooming into the drawing, all of the spaces were crafted with backstories and characters going about their lives! The events happening in the spaces directly shaped the architecture.

VT: What's most important to you when you design architecture?

MP: I believe uniqueness and peculiarity are the most important things I want to achieve. To reveal the unthinkable and the unseen, in a way.

Anyone can design architecture that we experience every day, but only you can unravel your unique visions and show them to the world.

VT: Finally, a word of advice to aspiring architects?

MP: Carve out your own path and focus on what you truly love and care about. Make your mark in the world.

Victor Hugo Azevedo and Cheryl Lu Xu Back to top

The following text is an interview between Viola Turrell of the Soane Museum Youth Panel and Victor Hugo Azevedo and Cheryl Lu Xu.

VT: What is your greatest source of inspiration?

VHA/CLX: We are inspired by the premise that everything is architecture or can become architecture. We are interested in seeing the world in a different way and going beyond what a certain thing looks like or is like. As architects, we aim to push boundaries and be forward thinking while taking into consideration the current state of the world, how global trends can influence our human experience and how we can shape the future.

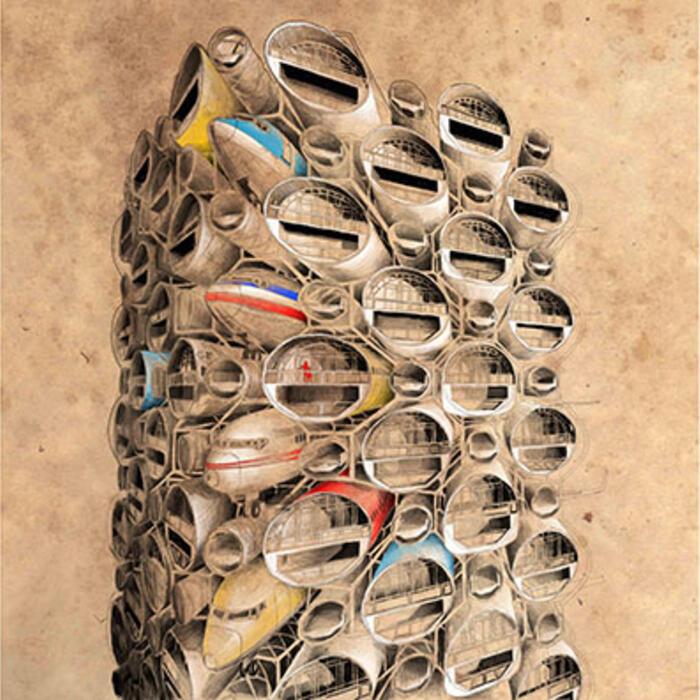

VT: What is the primary focus of your drawing?

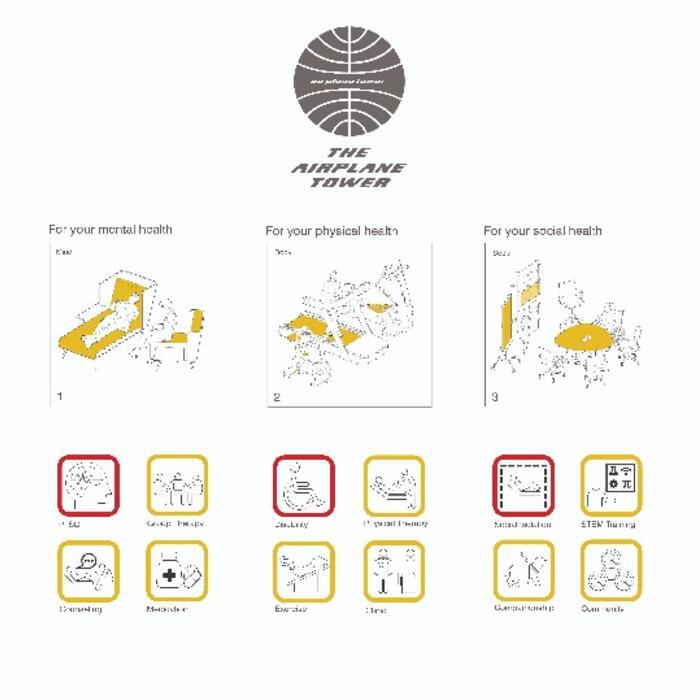

VHA/CLX: The primary focus of a drawing is to communicate an idea. In our case we wanted to convey the idea of a new type of skyscraper completely made out of airplane parts. In the drawing we clearly expressed the iconic shape of an airplane in the facade in order to convey our unique design intent.

VT: How do you consider human interaction/usage within your space?

VHA/CLX: Our goal with architecture is to create community, and in the Airplane Tower we created a central hub that houses various types of communal spaces that would encourage a multitude of opportunities for interactions between the residents.

VT: What's most important to you when you design architecture?

VHA/CLX: First of all, the most important is to come up with a 'big idea', a strong, compelling narrative that has relevance within the current global trends. We ask ourselves the question: ‘How can our design help make the world a better place?’, ‘What opportunities can we leverage?’

Finally, that narrative will guide us through the development of the project.

VT: Finally, a word of advice to aspiring architects?

VHA/CLX: Always be curious. Architecture is not only about buildings; it is mostly about life and the world that we inhabit. There are opportunities and inspirations at every corner, you just need to learn to see things differently. It's not so much about creating pretty pictures, but about invoking feelings, creating experiences and hinting at what the world could become.

Jono Yoo Back to top

The following text is an interview between Viola Turrell of the Soane Museum Youth Panel and Jono Yoo.

VT: What is your greatest source of inspiration?

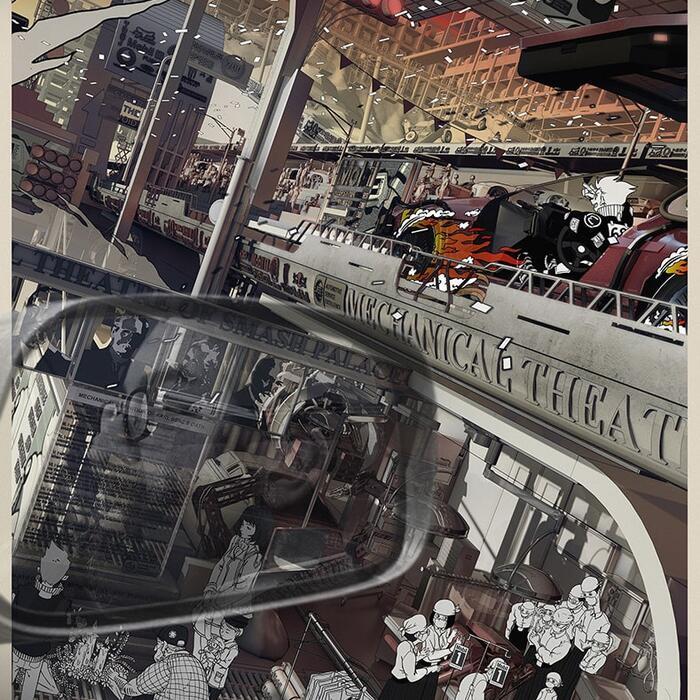

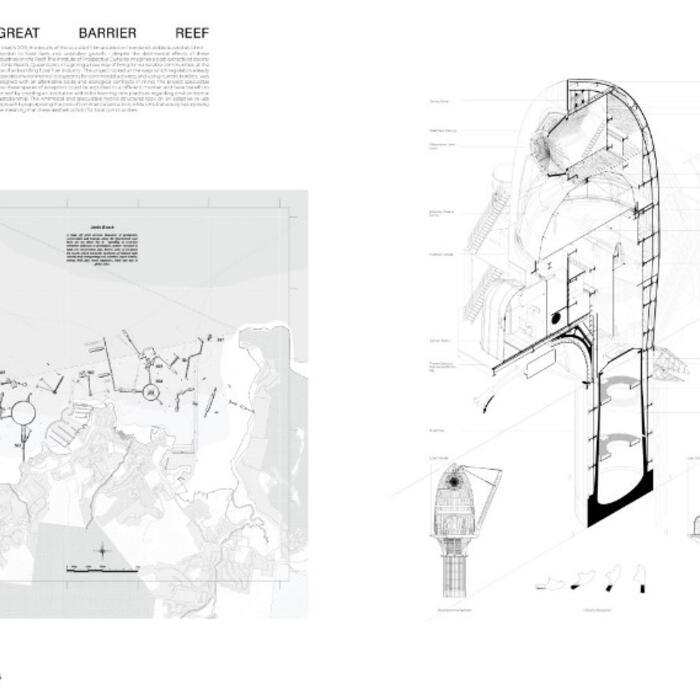

JY: It’s quite difficult to pinpoint what inspires my work broadly, as anything around us can be an inspiration. The automobile and its countercultures inspired my master’s thesis research project. My research concludes with five different fictional demonstrations of the countercultures, Mechanical Theatre of Smash Palace being a magnification into one of the most significant of countercultures the automobile has produced: car modification.

VT: What is the primary focus of your drawing?

JY: Typically, car tuning revolves around the modification of a car’s performance. However, over the century, various styles of modification were introduced to meet motorists’ personalised characteristics and preferences, such as Rat rod, Euro-style, Sleeper, Drag Car and Custom Car; the list is endless. Nevertheless, as far as its history goes, the very culture of car modification is, at its core, a particularly meaningful practice worth investigating as it involves the process of poiesis. The process of poiesis, namely, the process of making, is epitomised within the culture of car modification, rendering the motorists as the homo fabers. To elaborate on this, it is worth noting the definition of autopoiesis. This term indicates that human beings create and individuate themselves as unique and unrepeatable identity through the differences found in mutual exchange. Moreover, the term homo faber, Latin for ‘Man, the maker’, extends the idea of individuation through the concept that human beings can control their fate and their environment by ‘working’ and creating using tools.

Smash Palace aims to reinforce the culture of poiesis counter-formed from the automobile dispositif, where people make their own sign-values according to their personal needs, whether it be the car’s appearance or performance. Here in Smash Palace, the motorists become the makers, seeking to find their own meaning of the value of their beloved car, which is unique and different to each individual. Through undertaking this process, the motorist can create a personal ‘artefact’ that persists through time and embodies the creator’s identity and character; the car becomes an extension of identity transcending beyond a mere commuting machine. The process of self-disclosure through individuated sign-values re-identifies our society and its overly predicated sign-values, logos and brands.

In the post-consumer society, we do not necessarily take distinguished value into consideration when consuming a product. We often obscure ourselves by pursuing the sign-value predetermined by particular brands and the superficial social values it adds, inhibiting us from recognising the personal significance it has for each individual. The Smash Palace brings forth the culture of poiesis and empowers us to express our own unique sign-value. This is a place where ‘a car I bought’ can become ‘my car’.

VT: How do you consider human interaction/usage within your space? What's most important to you when you design architecture?

JY: Definitely people’s collective production/re-appropriation of space. In my thesis, I explore how the infrastructure of the car park becomes French philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s assemblage, where various social functions merge from an empty, meaningless structure to create a collectively formed spatial re-appropriation. In the carpark, the motorist’s liberating action sparks counter-spatialities of differentiation that are housed by an open system of indeterminate architecture.

At least in my thesis, architecture is merely empty, meaningless car park structures that house the collective production of space. Architecture should curate its indeterminacy and its users’ creativity, rather than projecting its rigid purpose on the users.

VT: Finally, a word of advice to aspiring architects?

JY: I personally believe that the way to go about in creative practice is to produce works that satisfy you the most. I guess there is a bit of truth in the long running quote: ‘the most personal is the most creative’.

Jeff Stikeman Back to top

The following text is an interview between Viola Turrell of the Soane Museum Youth Panel and Jeff Stikeman.

VT: What is your greatest source of inspiration?

JS: I have always wanted to build or to create or to draw things. An instructor in architecture school once told me that ‘everything we do should be beautiful. Not just the final work, but every step along the way’. My inspiration is simply a desire to make beautiful things, especially the things I consider beautiful, and to have fun doing it.

VT: What is the primary focus of your drawing?

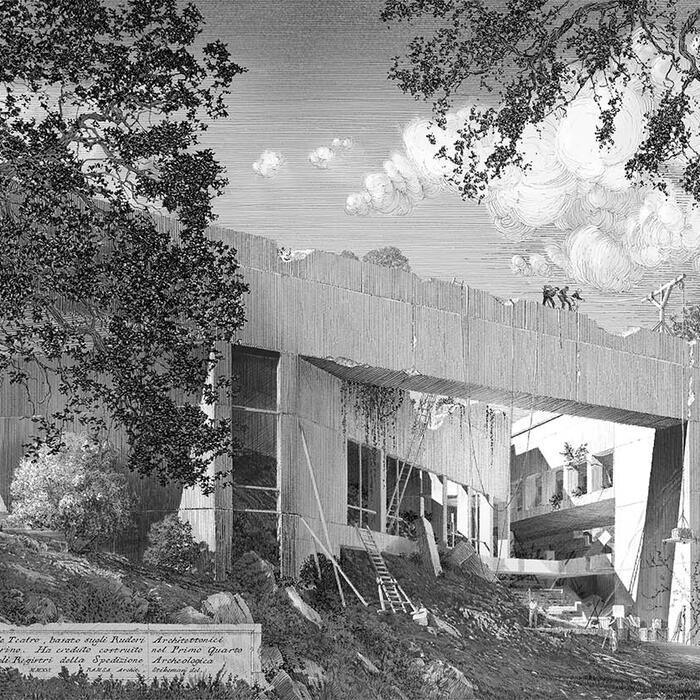

JS: I had done other, more conventional, renderings of this building which were used to present the concept to the School's trustees while the design was being developed. The Choate Colony Hall you see now, however, was to be a gift for my client’s colleague, who was a collector of Piranesi’s engravings. The idea was to capture his own building (not yet built) in a similar style, projecting both forward into the future – when the building might be a ruin – but also to look back, and to populate it with people and motifs found in Piranesi’s works and those of Hubert Robert, an 18th-century painter known for such images.

VT: How do you consider human interaction/usage within your space?

JS: As I am not the designer of this building, I instead imagined how people might use this building as a fantastical ruin: primarily, for shelter (there are two lean-tos in the image, one belonging to a swineherd).

Elsewhere in the image we see an abandoned cooking fire with a pot and cooking frame. The humans in our view belong to an archaeological team who have recently arrived and are recording the work (two surveyors, a man painting a record of the scene accompanied by a child), and those who are staging the ruins for a long-term excavation (see the men hoisting equipment to the roof, an ox-cart arriving with more equipment and stores, etc.).

The mascot of Choate-Rosemary School is a wild boar, and throughout the scene you can find a few wild boars and their piglets. Beneath the smaller tree at the centre, against a wall, is the lean-to of a swineherd who has fled the scene and left the animals to roam. These are motifs that appear in Hubert Robert’s works and I am paying homage to his expansive scenes of over-grown Roman ruins.

VT: What's most important to you when you design architecture?

JS: The experience. Architecture is a physical medium and all too often it is only designed in plan or in elevation, when in reality it is experiential, physical, three-dimensional.

VT: Finally, a word of advice to aspiring architects?

JS: Think in three dimensions, learn how buildings are actually built, understand your materials, and master the concepts of structural engineering. Imagine yourself moving through the spaces you are designing and do not commit too quickly to capturing things on paper or in digital models. The drawings and documents come after a building is designed, to record it. Test your options and let the building remain as fluid and flexible as possible before you choose a direction. When you are faced with choices, stick to your principals.

Jerram Rosen and Shahar Cohen Back to top

The following text is an interview between Viola Turrell of the Soane Museum Youth Panel and Jerram Rosen and Shahar Cohen.

VT: What is your greatest source of inspiration?

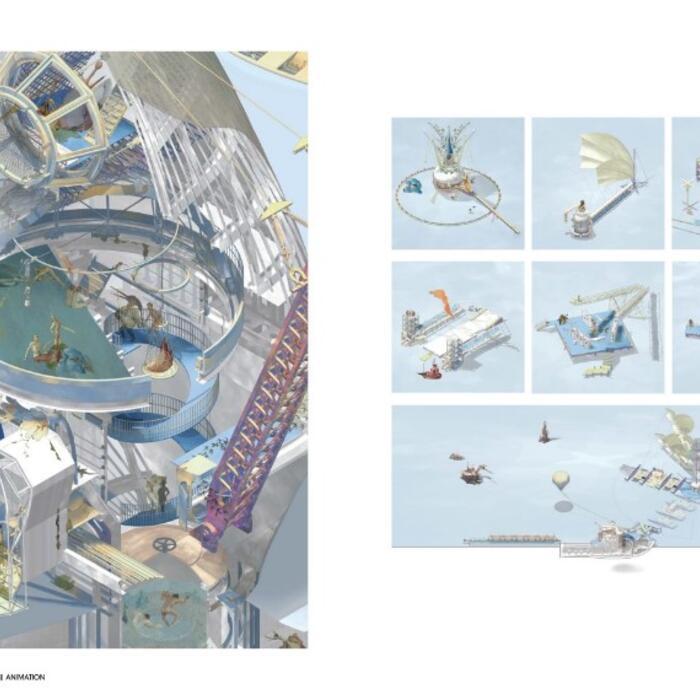

JR/SC: Within each of our practices, inspiration strikes at any given moment and almost certainly occurs outside the field of architecture. Practices such as animation, classical art and infrastructure are usually common sources in our work, where we aim to create spaces which question the relationship between fiction and reality. Significant practitioners that were used in The Theatre of Fictions as visual sources include Hieronymus Bosch, Paul B. Preciado, Ifigeneia Liangi, Daniel Agdag and John Hejduk.

VT: What is the primary focus of your drawing?

JR/SC: The focus of this drawing looks at the interplay between order and chaos, myth and reality, labour and delight. The intention of all our drawings is to always convey a narrative between characters inhabiting the frame. We are fascinated by images that suggest a before and after rather than a static, distant moment in time.

VT : How do you consider human interaction/usage within your space?

JR/SC: The Theatre of Fictions is a snapshot into a much larger marine ecosystem. Drawing on infrastructures of extraction, we looked at how space (and symbols of space) designed entirely for ‘productivity’ could be made redundant by reconfiguring their original programs. Spaces are configured from fragments of enormous machinery married with fantasy to create an between care, misuse and play at both a macro and tactile scale.

VT: What's most important to you when you design architecture?

JR/SC: Narrative. Being able to design begins with a story and having that story play throughout all scales of your project. Additionally, having a strong conceptual foundation and directly responding to immediate sociocultural issues.

VT: Finally, a word of advice to aspiring architects?

JR/SC: Take risks, iterate, look outside of the traditional tools and inspiration provided to you as a student, don't make critical decisions at the last minute and give yourself at least double the time you had planned to pursue graphic representation.

The Youth Panel is a group of young people aged 15–24 who help the Museum shape the activities, events and opportunities we offer young people. Meeting roughly once a fortnight, joining the Youth Panel provides a great opportunity to develop real skills that will be invaluable in a future career, whilst also meeting other young people, having fun and developing new skills and interests. Find out more