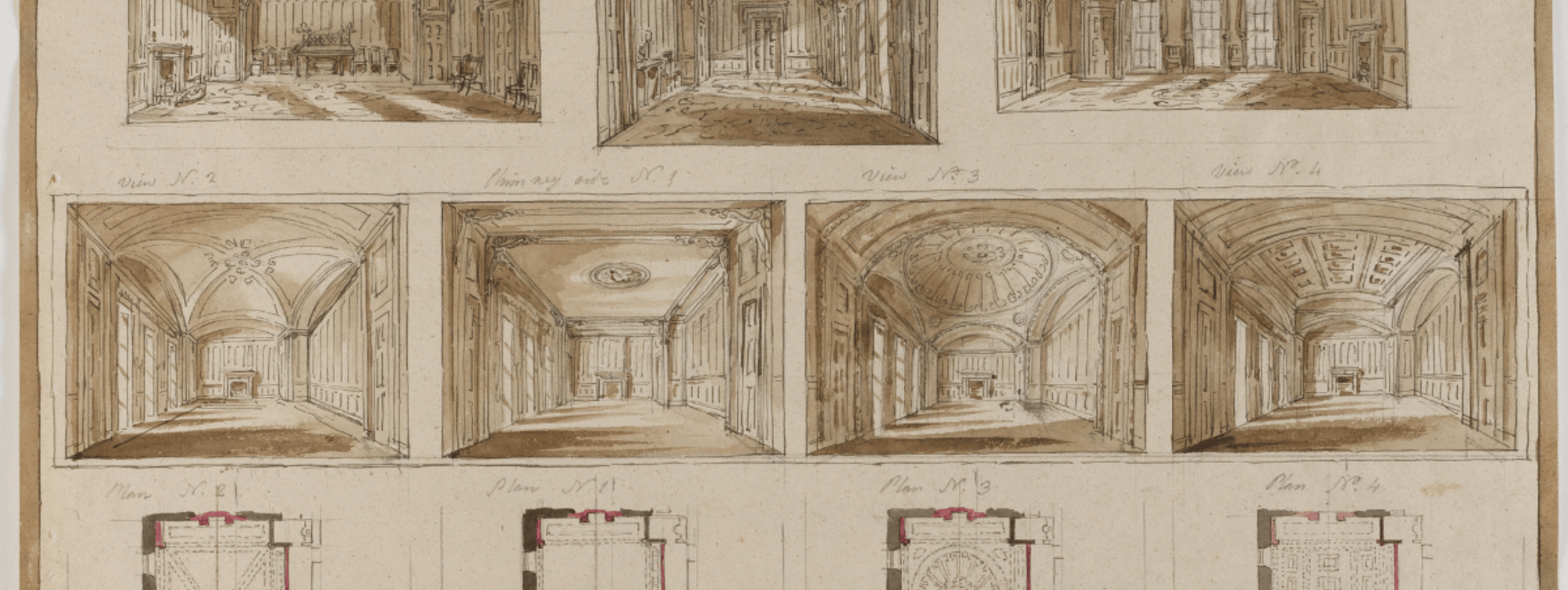

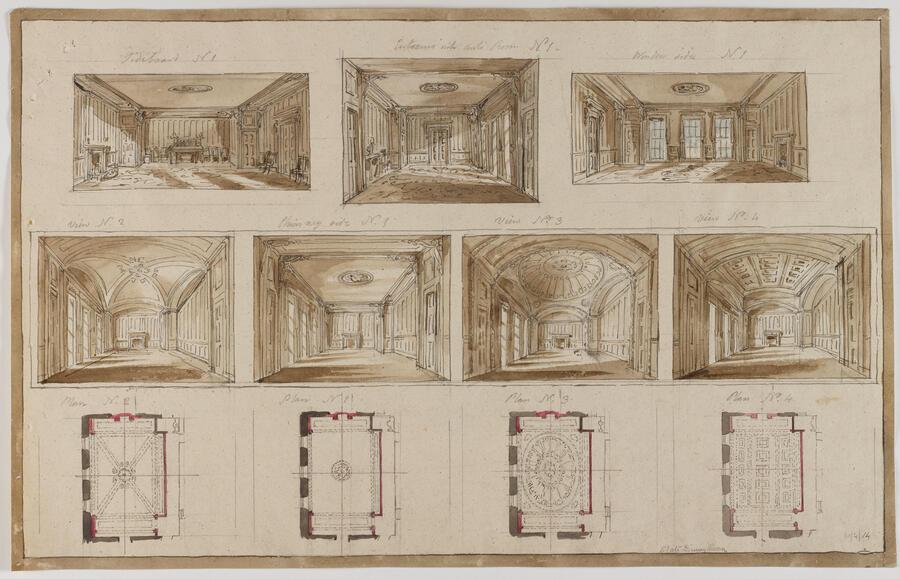

Above: Model for the domical ceiling to the Eating Room, No.11 Downing Street, 1825

War damage to the Downing Street buildings was quite impactful despite there being no direct hits by German bombs. Many fell close by, and photographs from the time show many of the state rooms covered with shattered window glass, and chunks of plaster from fallen ceilings. The Historic England Archive in Swindon is now home to countless detailed and fascinating Ministry of Works (MOW) photographs. These detail wartime damage and the progress of the extensive and thoughtful restoration of the whole 10-12 Downing Street complex by the eminent architect of the time Raymond Erith in the early 1960s.

World War II had taken its toll on what were already a rather ramshackle agglomeration of poorly constructed houses, much added to and altered in piecemeal fashion. Following adjacent bombing, the 18th-century refacing of the street façade was coming away from the building and leaning out at the top. Plans for a new lift were abandoned as the core of the building was too wonky and unstable, and the seasonal shift of the shallow footings on boggy ground meant a carpenter was employed almost full time to ease sagging doors and windows. Clearly a major reconstruction was required.

During the Prime Ministership of Sir Anthony Eden, the MOW Historic Buildings Department proposed a number of radical schemes to rebuild, including one completely eradicating the Downing Street buildings including all of Kent’s and Soane’s work. However, following the Suez crisis, Eden resigned, and Harold Macmillan took up the reins to instigate the reconstruction. Sir Albert Richardson had been in the running to get the job as all agreed that the in-house team at the MOW were not up to it. However, Eden himself suggested Raymond Erith who was significantly younger than Richardson, practically an octogenarian.

Erith was perhaps one of our greatest mid-twentieth century classical architects, and highly influenced by Soane in much of his work, and so today, there is even more Soanean detailing throughout 10,11 and the newly rebuilt 12 than there ever was in Soane’s day. The whole of the interior of the knocked together 1680s terraced houses that front Downing Street were stripped to a bare shell with new concrete floors inserted and significant underpinning carried out to ensure long term stability. Soane’s work at Number 10 was in a later and better built section, so remained largely intact.

The Number 11 Small Dining Room and adjacent ante-room however saw the most significant changes to Soane’s interiors. In quite a radical move, the entirety of Soane’s work in this area was removed: the plaster vault was cut into pieces and taken down along with the panelling and large arched headed window. These were stored off site whilst Erith constructed a whole new timber roof structure which he extended to create a new ante-room where none had been before. Soane’s original panelling was refitted and reconfigured to infill the original opening to the now eradicated ante-room, and then faithfully copied in the new ante space Erith created by pushing Soane’s window further out into the garden area. The plaster vault was tied back up to the new roof structure and joints seamlessly filled, so that today, none of this radical surgery is evident. In fact, so authentically detailed is Erith’s work, that eminent historians have been fooled by his modifications.

The removal of all traces of Soane’s ante-room allowed Erith to design a generous new staircase in Number 11 where the more modest original by Soane and its larger Victorian replacement once were. Erith copied the new staircase from one of Soane’s at Aynhoe Park. Furthermore, where Erith extended the dining room outward, creating a new space below, he purloined two cast-iron columns from Soane’s adjacent Treasury building (already much altered by Sir Charles Barry). There the MOW was responsible for a façade retention scheme running alongside the works at Downing Street, and therefore there was some architectural salvage to be had. In a final reference to Soane, Erith designed a new chimneypiece for the Small Dining Room based on one in Lincoln’s Inn Fields to replace the later Victorian one.

And so it is today that what most think of as a beautiful surviving gem of a Soane interior owes much to Erith and his sensitive but radical and historically confusing adaptation. He did however seek the approval of the then Curator of Sir John Soane’s Museum, Sir John Summerson. who wrote to Erith saying that the proposed extension ‘would be a great improvement’.

In Number 10, post-war restoration was much less invasive: the panelling of the Breakfast Room was removed, stripped of its white paint and then refitted with the oak repolished, but to a lighter shade than originally. The cornice here is in a Soanean style but designed by Erith. Chimneypieces throughout were removed for protection during the works, then restored and replaced. Unfortunately, the Soane original from the State Dining Room was broken during removal, and Erith drew up the design of its replacement to match the original as closely as possible.

It is testament to the importance of Soane’s work that it survived a period in our history when less significance was placed upon our historic fabric generally, and where wartime damage was often used as an excuse to ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater’. Luckily the foresight of those in power at the time, and an architect particularly sympathetic to the work of Soane, has ensured the preservation of his key interiors at Downing Street, adapted where necessary to continue to serve us some two centuries later.

- - -

Written by Simon Hurst