Sir John Soane understood the importance of architectural drawings. It was his skill in architectural composition and draughtsmanship which propelled him towards professional success, when in 1776, aged only 23, he won the Royal Academy gold medal for architecture with a design for a monumental bridge. Thereafter Soane was brought to the attention of King George III and was nominated for a scholarship to fund his Grand Tour, enabling him to study architecture in Italy, and to forge contacts with other British grand tourists who became his patrons. Unfortunately, many of Soane’s Grand Tour drawings were lost as he crossed the Alps on the way home, but the foundational importance of these experiences was never lost on him; he noted 18 March in his diary – the day he set forth in 1778 – almost every year for the rest of his life. On returning home in 1780 Soane established his architectural practice, and from 1792 he made his home and office at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

As the fourth Architectural Drawing Prize opens digitally on the Soane website, Curator of Drawings and Books, Frances Sands, explores the central role of architectural drawings in the collection of Sir John Soane's Museum.

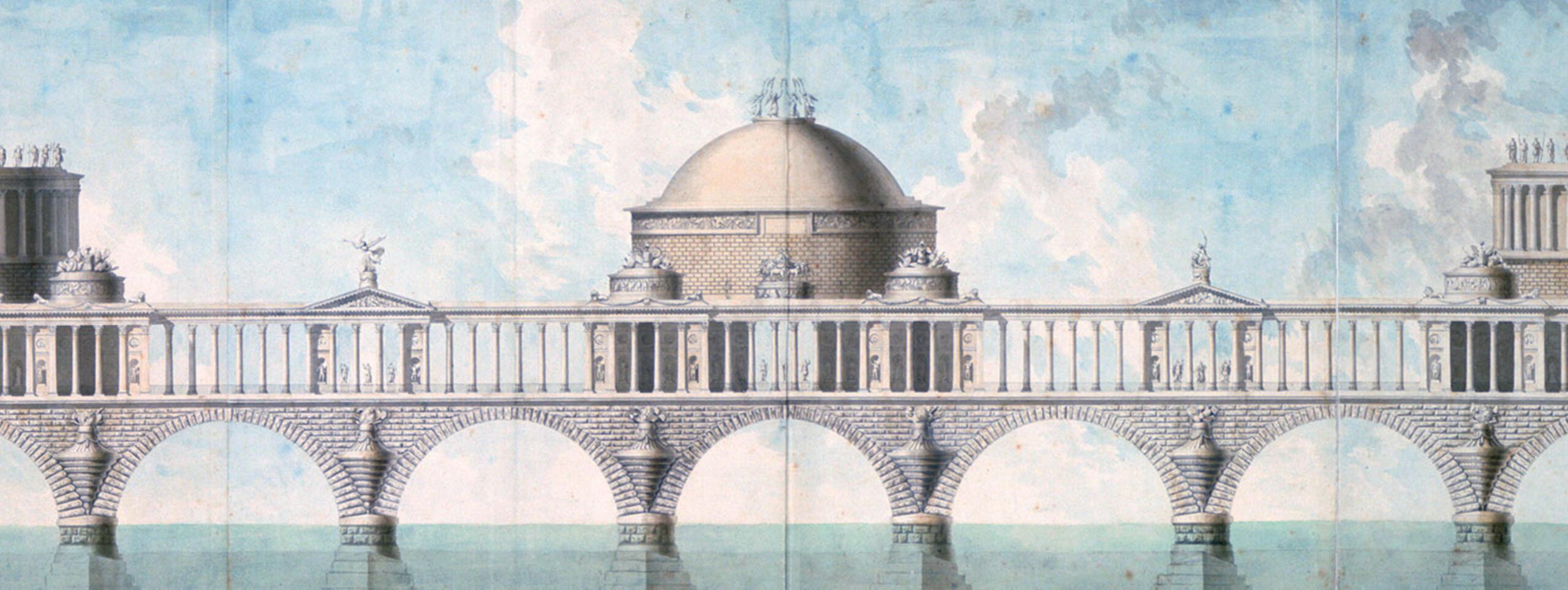

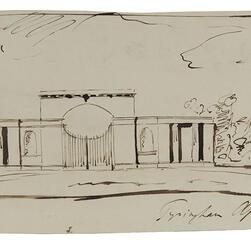

Joseph Michael Gandy, unexecuted design for an entrance into London, exhibited at the RA in 1826, SM P83. Photograph: Geremy Butler. ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

During his career, Soane collected some 22,000 drawings by other significant artists and architects. There are also 8,000 drawings surviving from his own office. Not only was Soane a prolific architect, he was also a teacher and prominent member of the RA. He exhibited there regularly, with drawings of his architecture by the pre-eminent artist Joseph Michael Gandy. Gandy’s exhibition drawings eloquently communicated Soane’s design genius, offering an idealised version of Soane’s work, devoid of worldly constraints such as budget, plot size or executed status. As such, the mesmerising and frequently fantastical content of the Architectural Drawing Prize entries would have been understood by Soane as kindred spirits to his own work.

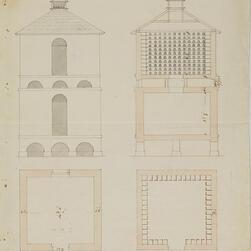

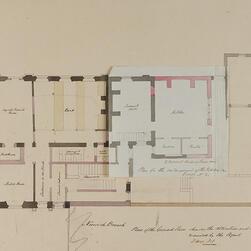

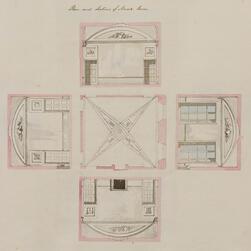

Left: George Bailey, Plans, elevation and section for a pigeon house, Cricket Lodge, Cricket St Thomas, Somerset, 1807, 65/1/6. Middle: George Bailey, ground plan with a flier, Bank of England Norwich branch bank, 1829, SM 56/12/33. Right: Soane office, laid-out wall-elevations for the music room, Taymouth Castle, Perthshire, c.1808-9, SM volume 65/22.

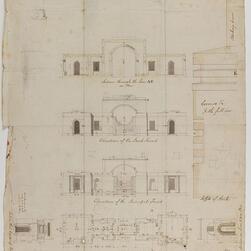

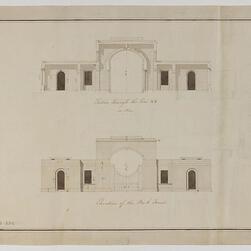

Less glamorous than Gandy’s exhibition drawings, the everyday work of Soane’s office typically focused on drawings for architectural commissions. For each project they produced a variety of drawings: the majority being plans, elevations, sections or perspective views. A plan illustrates the footprint and sometimes the internal arrangement of a building; an elevation shows the building orthogonally – head-on; a section cuts through a building, either axially or longitudinally; a perspective view gives a naturalistic pictorial representation with one or more vanishing points. Each format had appeared in England at different times, but all were commonplace by the seventeenth century. And by Soane’s lifetime other – less-used but helpful – options had emerged, such as bird’s-eye views; cutaways; fliers, which overlay an alternative concept; and laid-out wall-elevations, which offer the walls and floor or ceiling of a single room, displayed like a cardboard cut-out.

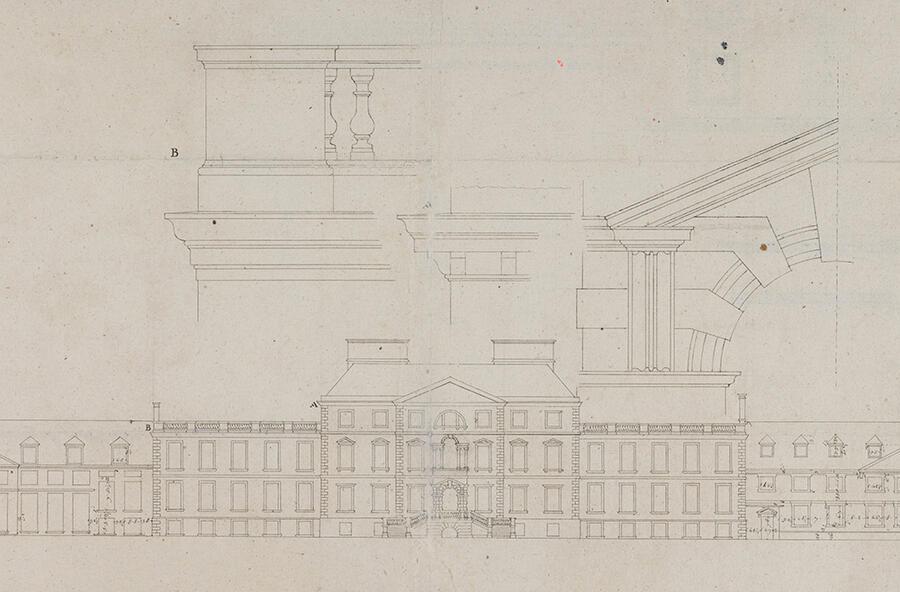

Certain drawing formats are easier for the layperson to interpret than others and therefore the elevation and perspective view predominated in architectural publication. Soane produced seven publications as a means of disseminating his work. Illustrations were engraved, with Soane providing drawings to the engraver. Like his exhibition drawings, these depicted only the designs with which Soane was most pleased, and tended to be orthogonal or topographical elevations and perspective views, but rarer are more detailed, structurally complex plans and sections.

Soane office, survey drawing of Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire, south fronts with details, 1790, SM 6/1/3. Photograph: Ardon Bar-Hama. ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

Irrespective of where a drawing appeared in the process of design through to construction, or even publication, the Soane office created more than one copy. Drawing production was multi-layered. First, a draughtsman was sent to the building site to make survey drawings of the topography and pre-existing architecture. This provided Soane with contextual information for his designs. As the function of a survey drawing was to relay an accurate representation, they are drawn simply, but to scale or thoroughly dimensioned, and without distracting ornamental flourishes.

Next Soane produced rough preliminary designs in order to develop his initial ideas. These were usually sketched to a rough scale, in pencil or pen, and without the hindrance of wash. A draughtsman then worked-up the design to scale, translating Soane’s sketch into a cohesive design. Such designs were regularly overdrawn by Soane as they evolved, but once he was satisfied with the composition, a finished drawing – a neat version – was produced, washed in grey or colour, and often collaborated upon by more than one draughtsman, depending on their differing skills. If this finished product met with Soane’s approval, then it was presented to the client to explain Soane’s design ideas with the hope of execution.

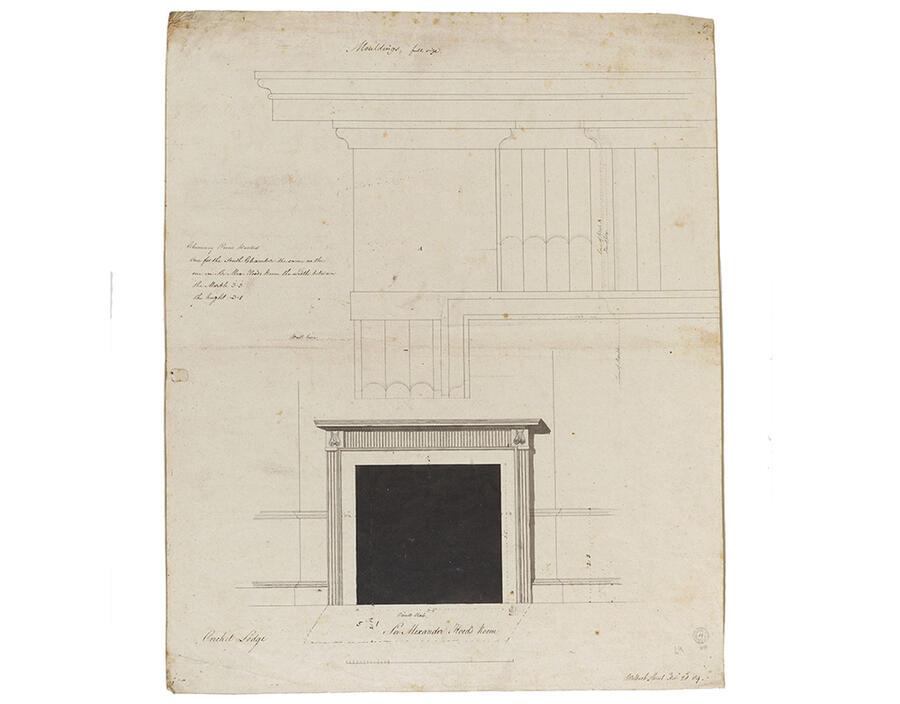

John Soane, working drawing for the first-floor chimneypieces at Cricket Lodge, Cricket St Thomas, Somerset, 1789, SM 81/1/69. Photograph: Hugh Kelly. ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

Should Soane’s client approve the presentation drawings, an entirely new series of drawings were required. Presentation drawings were works of art, conveying an alluring concept, but they did not provide enough detail for the building process. It was then necessary for the office to provide dozens or even hundreds of working drawings; each detailing one small element of the scheme. Drawn to scale or full size, and annotated with relevant information, these provided comprehensive instructions to the executant artisans, in order that Soane’s designs might be faithfully reproduced in three dimensions.

Eighteenth-century architectural offices were increasingly meticulous, establishing a convention for record drawings that would reproduce any designs offered to clients. These documented the office’s work and prevented any embarrassing repetition. They were drawn to scale, albeit to a reduced size as paper was expensive, and they were often only partially washed, or annotated with notations of colour, in order to maintain economy. As record drawings duplicated designs which Soane considered complete, they are rarely overdrawn or altered. There are 18 surviving volumes of Soane office record drawings.

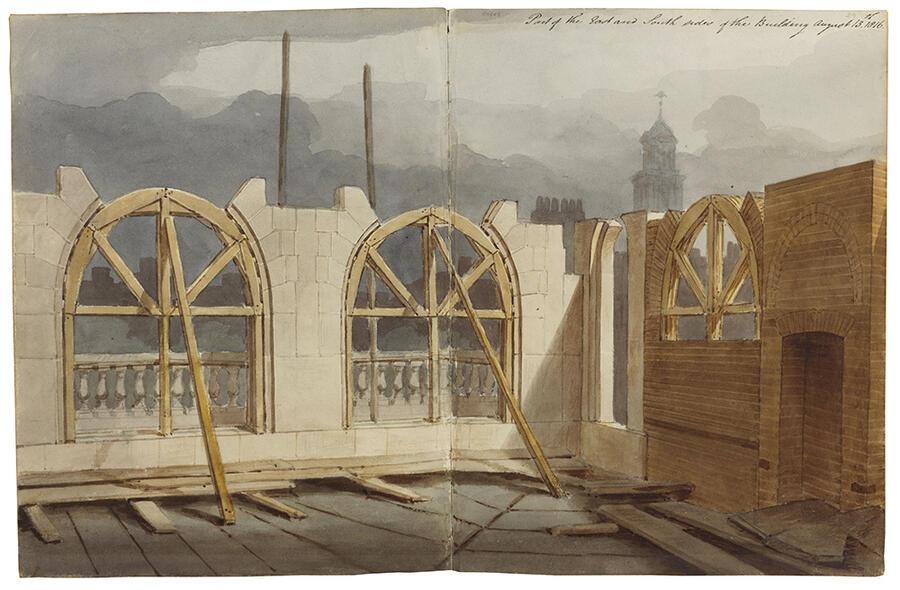

Henry Parke, progress drawing showing the office over the Reduced Annuity Office, Bank of England, London, 1816, SM volume 46/29. Photograph: Hugh Kelly. ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

In order to keep pace with the number of drawings required of his office, from 1784 Soane accepted articled pupils. He took his pedagogical responsibilities seriously, stressing the importance of draughtsmanship, accurate estimates, and an understanding of construction. The pupils’ training generally comprised relevant errands and drawing work – training drawings being yet another type of graphic representation – but from 1810, they also visited Soane’s local building sites, tasked with producing progress drawings. A sketch was made in situ and on returning to the office this was beautifully redrawn and washed. Seemingly rare at the time, progress drawings were not a means of updating Soane on the project, but rather, they were didactic: prompting scrutiny of the construction process.

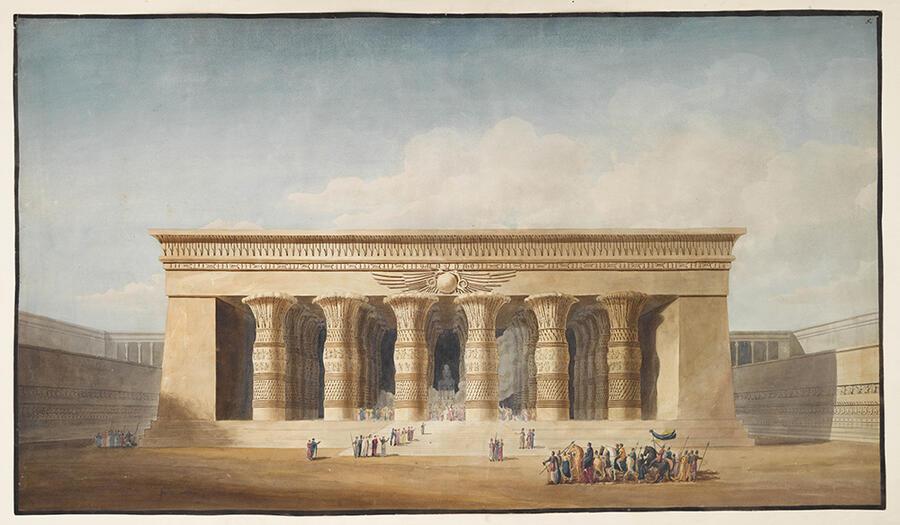

Soane office, RA lecture drawing showing an Egyptian temple, c.1806-19, SM 24/7/2. Photograph: Ardon Bar-Hama. ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

In 1806 Soane was elected Professor of Architecture at the RA, an ideal calling for an architect who took such care over training his articled pupils, and he compiled 12 lectures detailing the history of architecture. As the Napoleonic War raged, it was difficult for Soane’s RA students to take a Grand Tour as Soane himself had done, so Soane philanthropically provided work for his office during the lean years of conflict, commissioning 1,000 large-scale lecture drawings to illustrate his RA lectures. These are thought to comprise the earliest attempt at a graphic history of world architecture, and are a masterful pedagogical effort. From 1812, Soane invited his RA students to peruse the lecture drawings, along with the wider collection at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, on the days before and after each lecture. And so his Museum was born.

The 8,000 Soane office drawings illustrate the variety and quality of Georgian architecture, and Soane preserved them in order to inform and inspire architects of future generations. They were produced with goose feather pens and horse hair brushes, as opposed to the modern utensils and computer programmes used by the shortlisted artists of the Architectural Drawings Prize, but Soane would have admired the skill, creativity and understanding of architectural history that is evidently still flourishing.

Banner image: John Soane, design for a monumental bridge to cross the River Thames, this drawing won the RA gold medal, 1777, SM 12/5/4. Photograph: Geremy Butler. ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.