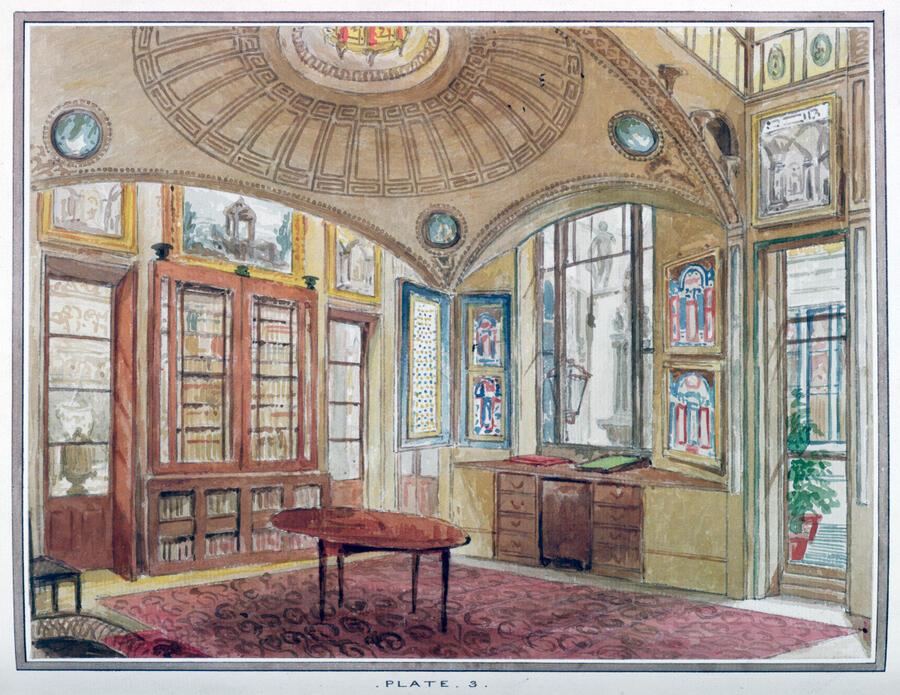

View in the basement of Sir John Soane’s Museum looking from the Basement Ante-Room towards the Sepulchral Chamber, watercolour, dated 14 November 1825, SM Vol. 82/50

Picturesque theory stressed that you should not pass abruptly from one scene to another, but that each should be connected by ‘some third species [of scene] which participates of both’. Soane achieves precisely this effect with what I would call transition spaces. The Lobby to the Breakfast Room, for example, provides an intense experience whilst transiting from the Breakfast Room to the Dome. First providing an unexpected vista from the north-west corner of the Breakfast Room and then a foretaste of the Dome as it is almost a mirror of it, but in miniature – a double-height space, piled high with works of art. Both spaces are viewed from what might be described as a ‘terrace’, over a railing or parapet, just as you might view the different levels of a garden. Similarly, the Museum Corridor provides a transition between the Colonnade and the Picture Room. The Colonnade is described as having a ‘rich variety of outline’ and offering ‘pictorial effects, from the catching lights and shades’. This language makes a direct comparison between what Soane was trying to achieve in architecture and the technique of a painter. In the basement, the Catacombs and other small, narrow passages provide transitional spaces and varied, asymmetrical routes and vistas to heart of the area, the Sepulchral Chamber, containing the sarcophagus of the Egyptian King Seti I, Soane’s greatest treasure.

Amongst the constituents of a ‘correctly picturesque’ landscape, a ruin – preferably of an abbey or castle - was considered a vital feature. Here too, Soane’s house fulfils the brief, with the mock-medieval ruins of an abbey in the Monk’s Yard, composed of fragments salvaged from the medieval palace of Westminster. In the 18th century there was a fleeting fashion for employing a hermit to animate a picturesque hermitage in a landscape – John Soane created his own imaginary solitary hermit, supposedly a former occupant of his mock abbey, whose tomb is set amidst the ruins. This holy father was his own alter ego, bearing the name Padre Giovanni (‘Father John’): with his creation Soane made himself a feature of the picturesque landscape he created in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

The https://shop.soane.org/products/sir-john-soanes-museum-timed-ticketingMusuem reopens on 1 October. Entry is by free timed ticket. Book yours online today.