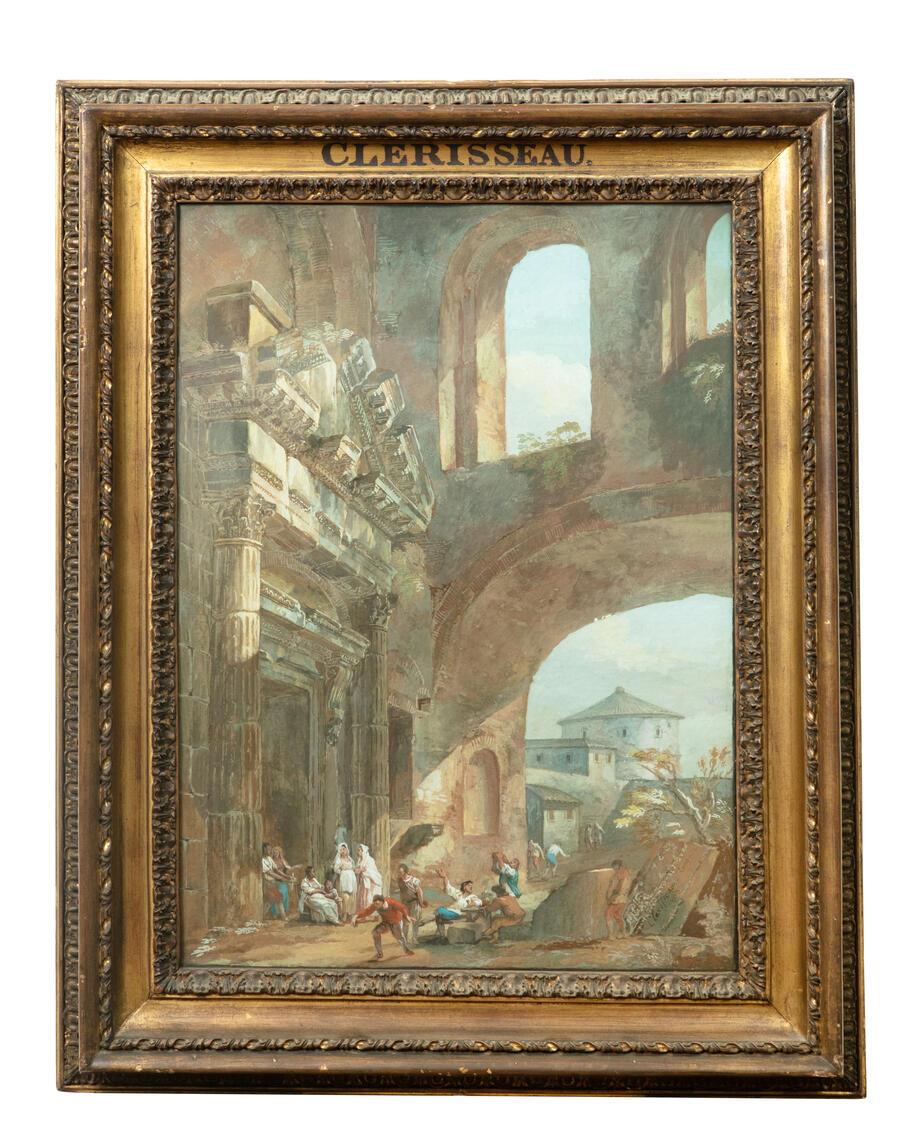

Interior of an Ancient Chamber by Charles-Louis Clérisseau

The work on these frames is part of a project which began a couple of years ago but because of the pandemic will only be completed next month. The project was prompted by a general review of the risks to artworks from light exposure, after which it was decided that the fifteen works on paper that hang in the recess of Soane’s Picture Room should be removed as a matter of urgency. After many years of display in this space, which is top lit from a skylight, they had suffered visible light damage.

The plan was to replace the fifteen paintings with high quality facsimiles which would be displayed in the original frames. First, we removed the pictures from their frames and, after conserving them, put them into permanent storage in a new purpose-built plan chest. Next, we began the process of producing the facsimiles, which proved both complex and time consuming. Each painting had to be scanned, and the scans painstakingly colour corrected by the printer, with direct reference to the original so that all the colours were accurately matched. It took three days to prepare the prints which were produced on Hahnemühle Rag paper using water based-inks. The results were excellent. Two of the fifteen were the pair of gouaches by Clérisseau and the facsimiles for these are particularly successful.