In 1834 Sir John Soane bought 20 white plaster-of-paris models by the Parisian model-maker François Fouquet for the new Model Room he was creating on the second floor of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields in what had been his wife’s bedroom. These exquisite models were displayed to illustrate how ancient buildings might have looked when new and pristine and were placed alongside cork models depicting them in their contemporary ruined state.

In October 1940 three of the Fouquet models were badly damaged by bomb blast during an air raid. Although described at the time as damaged beyond repair, fortunately they were retained, patched together using some kind of Polyfilla-like material and stored. It was not until the 1990s that they were finally taken out and considered for restoration. The least-damaged of the three was repaired successfully but two remained in store until 2015 when they were entrusted to the specialist plaster architectural model-maker Timothy Richards for restoration at his studio in Bath.

This clip follows the restoration of the final model, of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates especially interesting because Fouquet based it not on the ancient Greek original in Athens but on the so-called 'Lantern of Demosthenes', a tall, tower-like folly, built in 1801 by Napoleon I in the park of the Château of St Cloud, Paris. The top two sections were loosely based upon the classical monument. The open circular structure contained a bust of the Emperor (replicated in miniature in Fouquet’s model) and the Lantern was intended to be illuminated to indicate that Napoleon was in residence at the Château!

The damaged model Back to top

Tim Richards approached this restoration already in awe of the extraordinary detail and accuracy of Fouquet’s work and with the aim of retaining as much as possible of the original material. The model was badly broken, with some parts missing completely. It had also been damaged by damp which had caused some areas of plaster to expand and crack while other areas had rust-coloured staining around exposed metal armatures.

Dismantling the model Back to top

The first task was to remove the model from its wooden base, unscrewing the bolts that held it in place from underneath and separating the two – perhaps for the first time since the model was made in around 1820. On then could Tim start to work on damaged, loose areas of plaster, trying to do as little damage as possible. He first inserts a scalpel carefully into an existing crack between a stable and unstable area before gently lifting and easing out the broken section – separating it along an existing fracture. As the piece is lifted clear the condition of the plaster behind it can be seen: fortunately, no more excavation is needed and it can just be carefully eased back into its original position.

Casting the missing elements Back to top

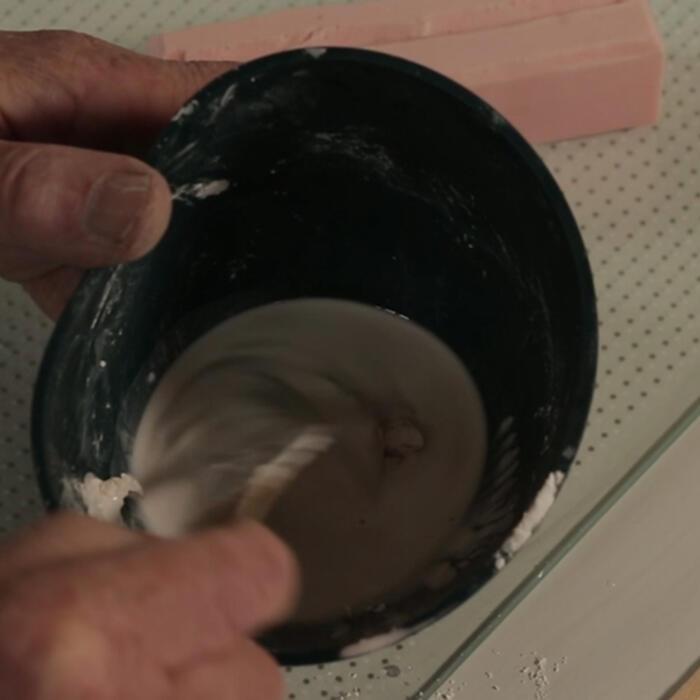

More intervention is needed to replicate and insert missing elements. The film shows the process of making new sections of fluted column using silicon rubber moulds taken from the surviving sections. Plaster is mixed with water very thoroughly (taking about ten minutes) to ensure there are no air bubbles, before being poured into the mould. The plaster is agitated with a brush once in the mould to ensure it fills every tiny groove. Once it is fully set the flexible mould can be eased apart and the new casting lifted out.

Assembling the model Back to top

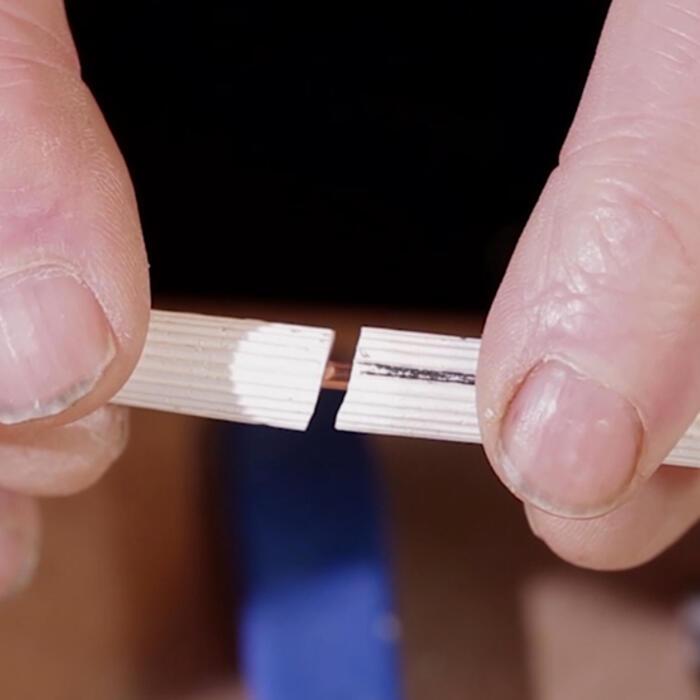

The next stage is that the metal rods within the original columns have to be cut to divide the model into two halves. This intervention is essential to enable Tim to slide new sections of column onto the rods to replace missing sections. There is then a long process to marry up the new pieces with the old. First, a length of new plaster column is placed alongside the old and marked up in pencil before being roughly cut to size. The end of the new section is then gradually pared down so that it fits against the broken end of the old section perfectly. Once the new sections are finished, they are glued into place. As Timothy Richards observes, it would be much easier to replace a whole column, but the aim of the restoration is to preserve as much of the original model as possible.

By autumn 2019, with its base repaired, broken columns once more complete and every miniscule tile of the roof perfect, the model was ready to return to the restored Model Room and reunite the 20 Fouquet models for the first time since World War II.

For more information about Timothy Richards' work, visit www.timothyrichards.co.uk