This selection of 22 drawings has been chosen as an introduction to the art of architectural drawing. It explains what the drawings were for and how they were made. All the drawings shown are in the collection of Sir John Soane’s Museum, either those made by Soane and his assistants and pupils, or the work of other architects which Soane collected. He had one of the very best collections of drawings put together by an architect, which he used for his own work and to instruct the pupils and assistants in his office. Soane left his house, together with his collections, to the Nation as a Museum, which is why you can visit it today.

Architects today still make similar kinds of drawings to those in this selection, but now they mostly work on computers. These drawings are often the work of more than one person, as the skills needed to make different kinds of drawings are quite difficult to acquire and in a big architectural office people tend to specialise in one particular kind of drawing.

Working in Soane's Office Back to top

This section tells you about what it was like to work in Soane’s office, where the office was and how the pupils and assistants were expected to reach it. It also shows where Soane himself worked. There is a drawing made in Soane’s office to show all his built projects up to 1815. We see the kind of pen made from a goose feather which Soane and his pupils would have used.

Soane was one of the most successful architects of his time and parents would pay to send their sons – only men worked in his office – to be trained to be architects. They worked for 12 hours a day, later reduced to 11. In the summer it would be hot and in the winter dark and cold. They had to use a door at the back of the property so they didn’t walk through the house, and they weren’t allowed to mix with the domestic servants. A few of them didn’t prove good enough and didn’t work there for long. When they started, Soane would see how good they were at drawing by getting them to draw the rooms in the Museum. They would be with him for five or six years, learning to draw and design buildings and all the business which was related to architecture.

Types of Drawings Back to top

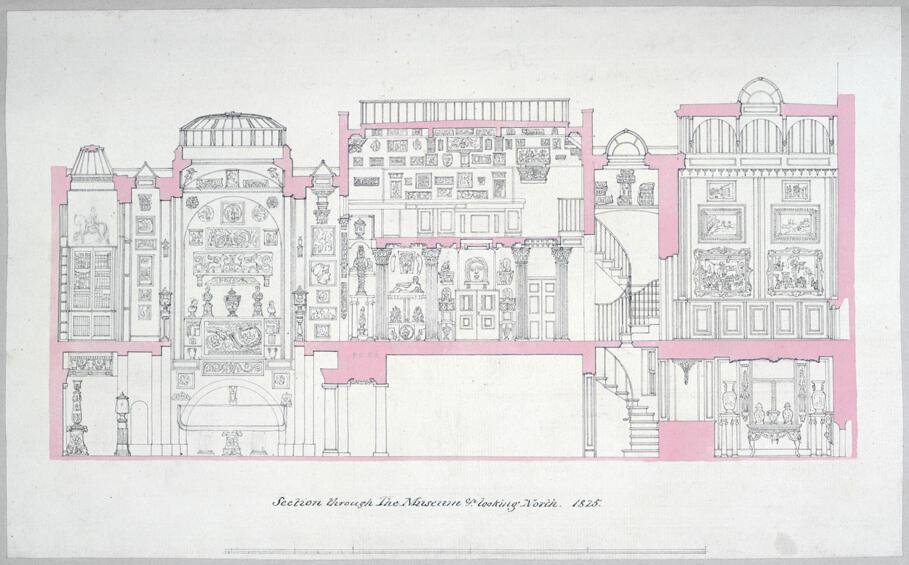

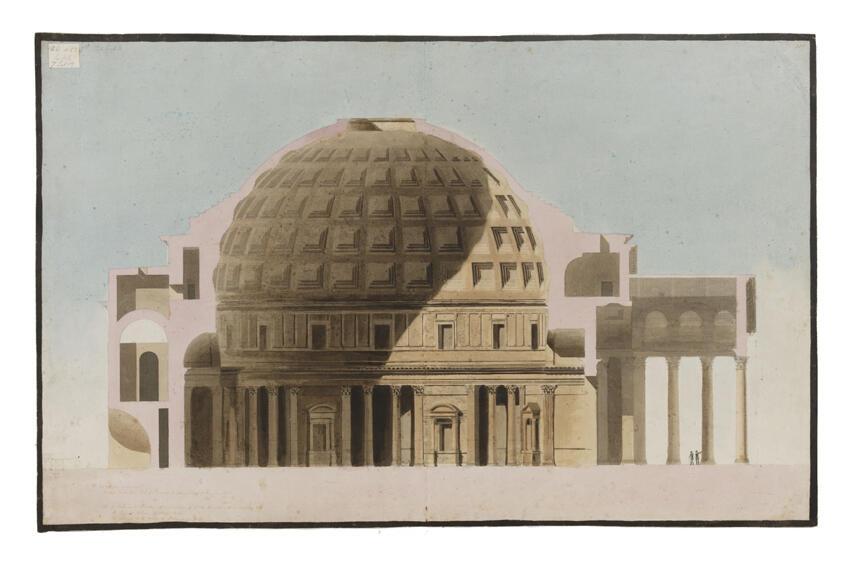

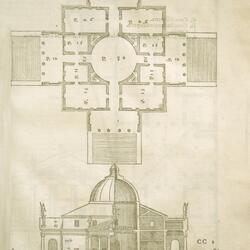

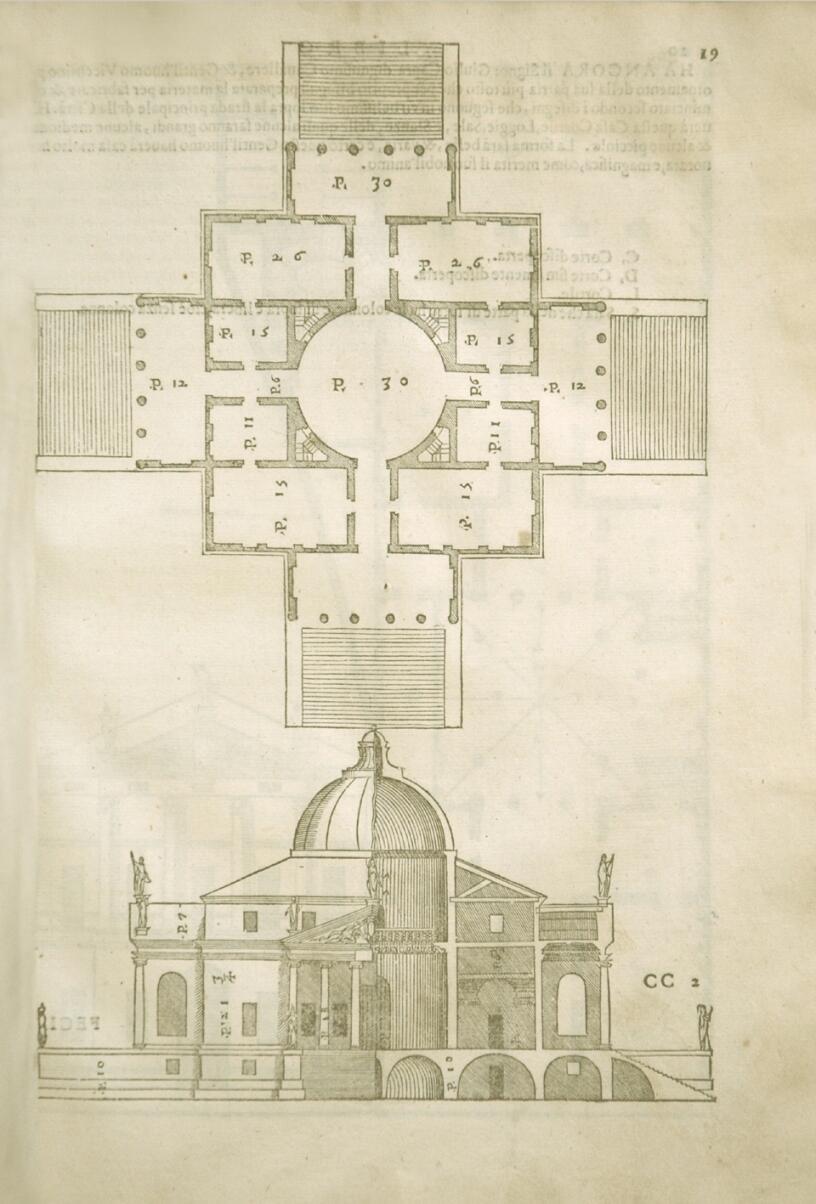

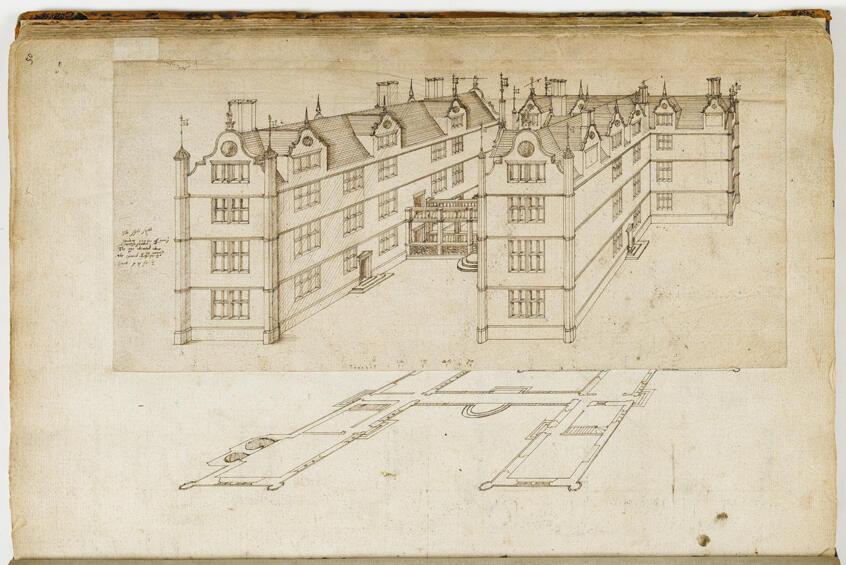

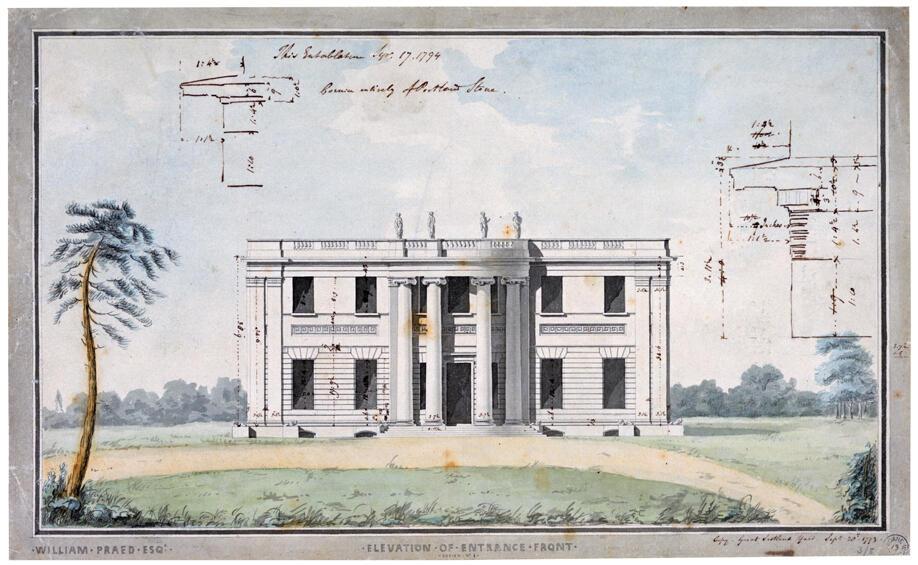

This section shows the different types of architectural drawings there are and what they are for. It shows the main four kinds of drawings: elevation, plan, section and perspective; together with more specialised kinds of drawings: bird’s-eye view and floor plan with laid-out wall elevations.

Some important buildings are shown: the Pantheon in Rome, one of the greatest Roman buildings to survive; Soane’s own country house, Pitzhanger Manor in Ealing and Lady Williams Wynne’s room, St James’s Square, designed by Robert Adam, whose drawings Soane bought for his collection.

Uses of the Drawings Back to top

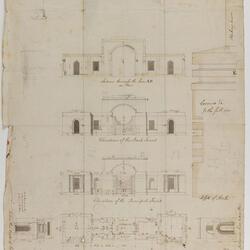

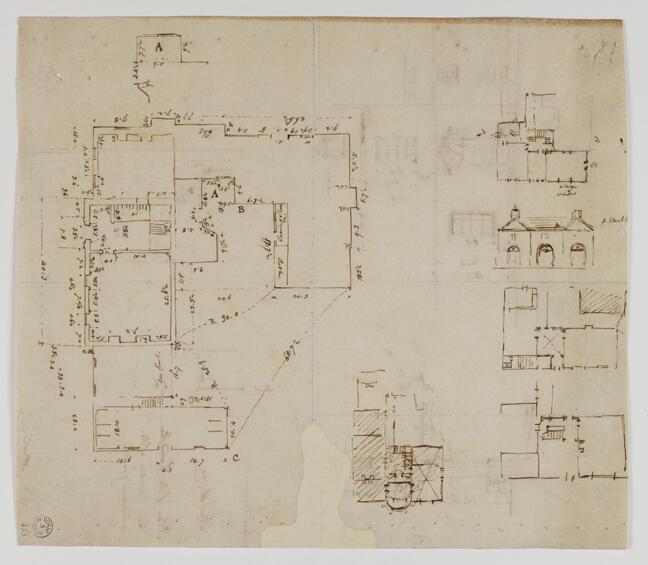

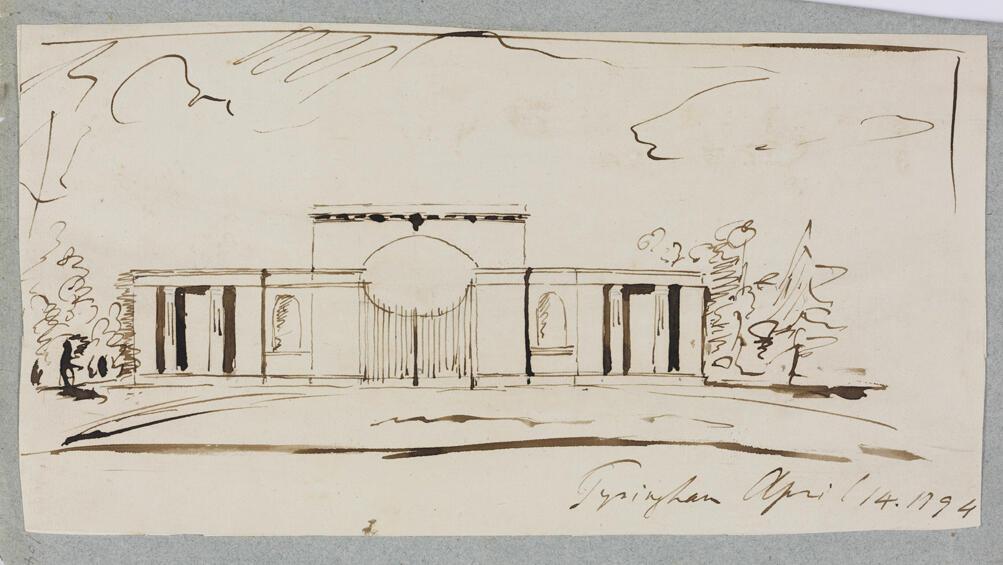

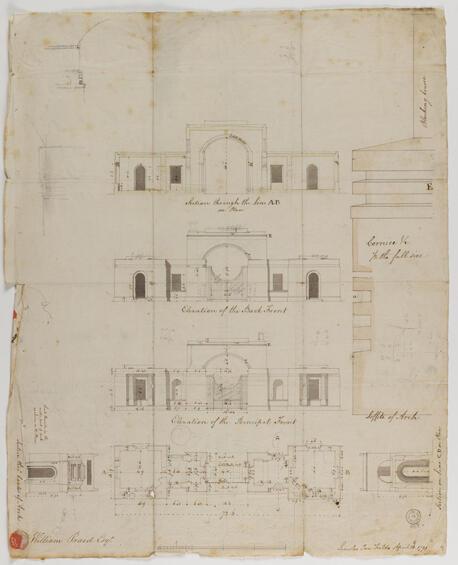

This section discusses what the drawings were for. We show a survey drawing of an existing building, one of Soane’s own sketch designs and the working drawing sent to the builder in the form of a ‘letter’ for the same building – the Tyringham Gateway. There is also a full-sized drawing of a detail in Soane’s greatest building – the Bank of England.

Learning from Drawing Back to top

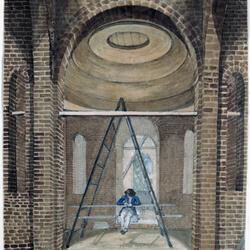

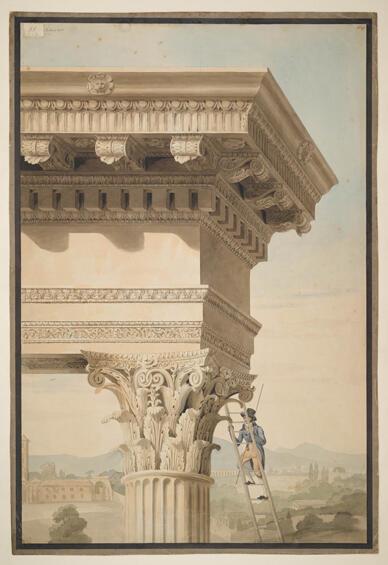

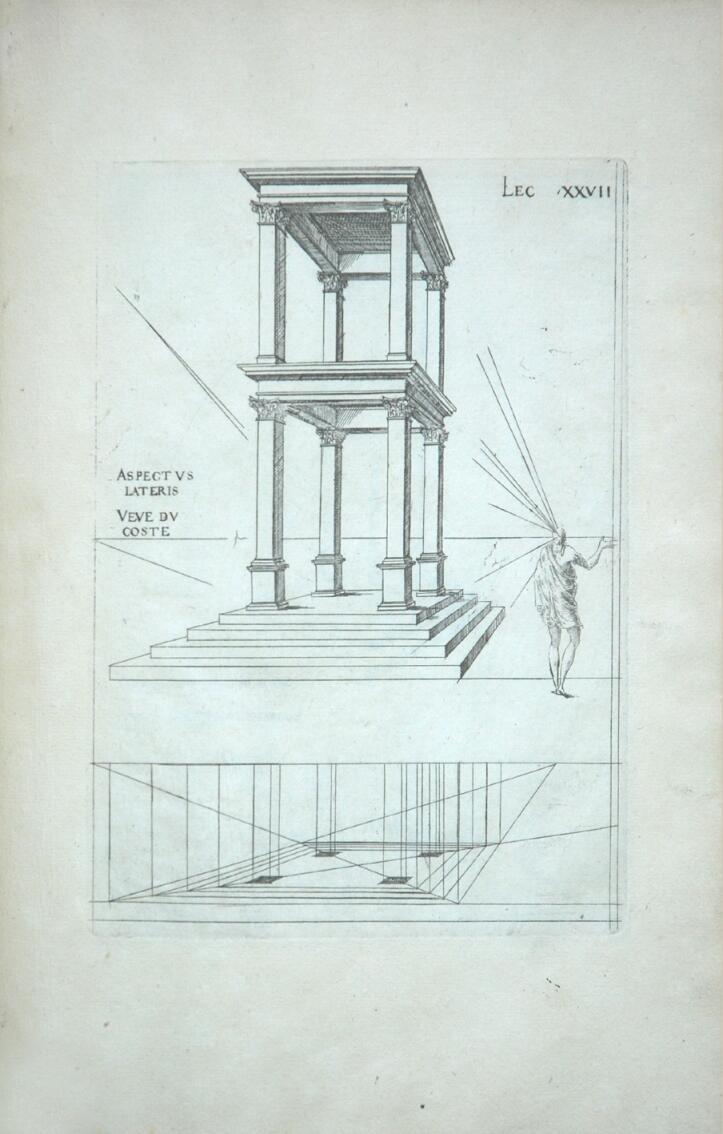

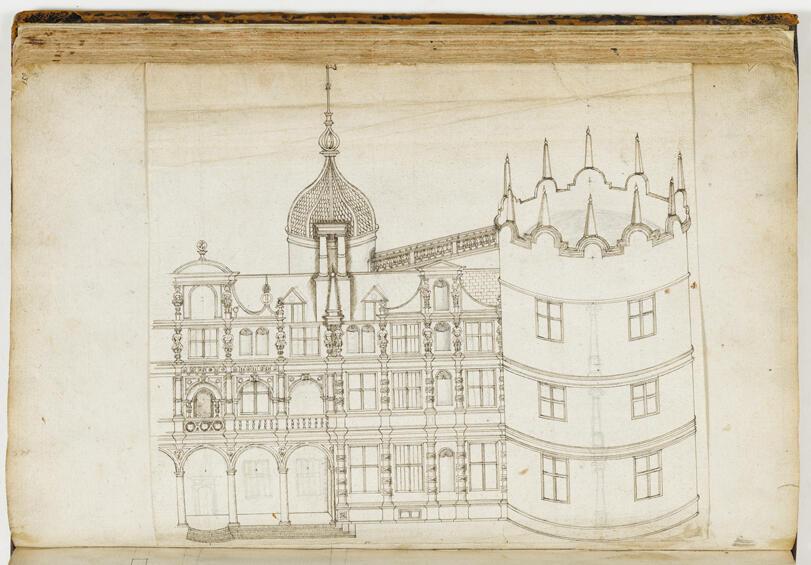

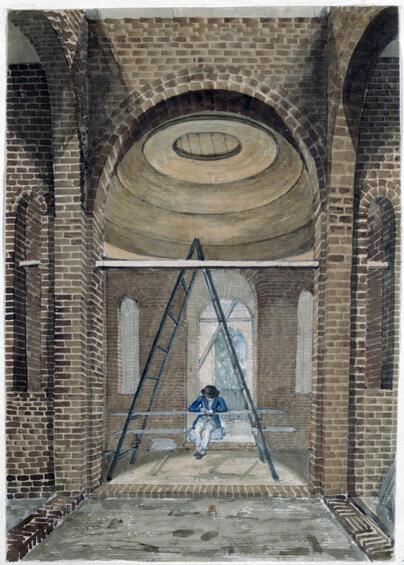

In this section we see how Soane’s pupils and assistants learnt from drawing. We see a young architect measuring one of the great Roman temples and we see how, in England, the art of perspective developed in the sixteenth century and the kind of books from which one could learn about architectural design and perspective. Lastly, we see one of Soane’s pupils drawing on site to record and learn about the process of construction.

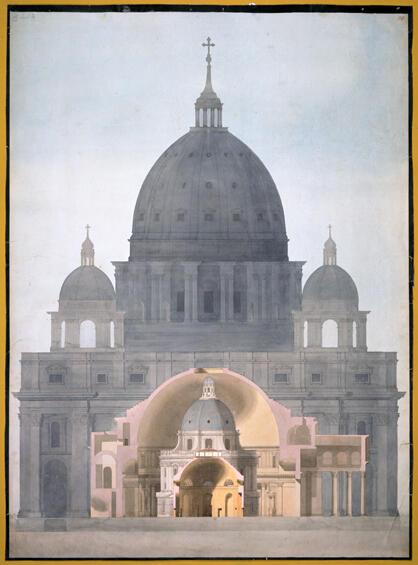

Drawings for Clients, Exhibitions and Lectures Back to top

Here we see the sort of highly-finished drawings Soane would had had made to show a client how the building he designed for them would look. We also see the drawings which were made for exhibitions which were an essential way to show his skills as an architect, and we see the sort of drawings he had made to illustrate the lectures he gave at the Royal Academy as Professor of Architecture. This section contains an extract from one of his lectures which is illustrated by the drawing of domes.