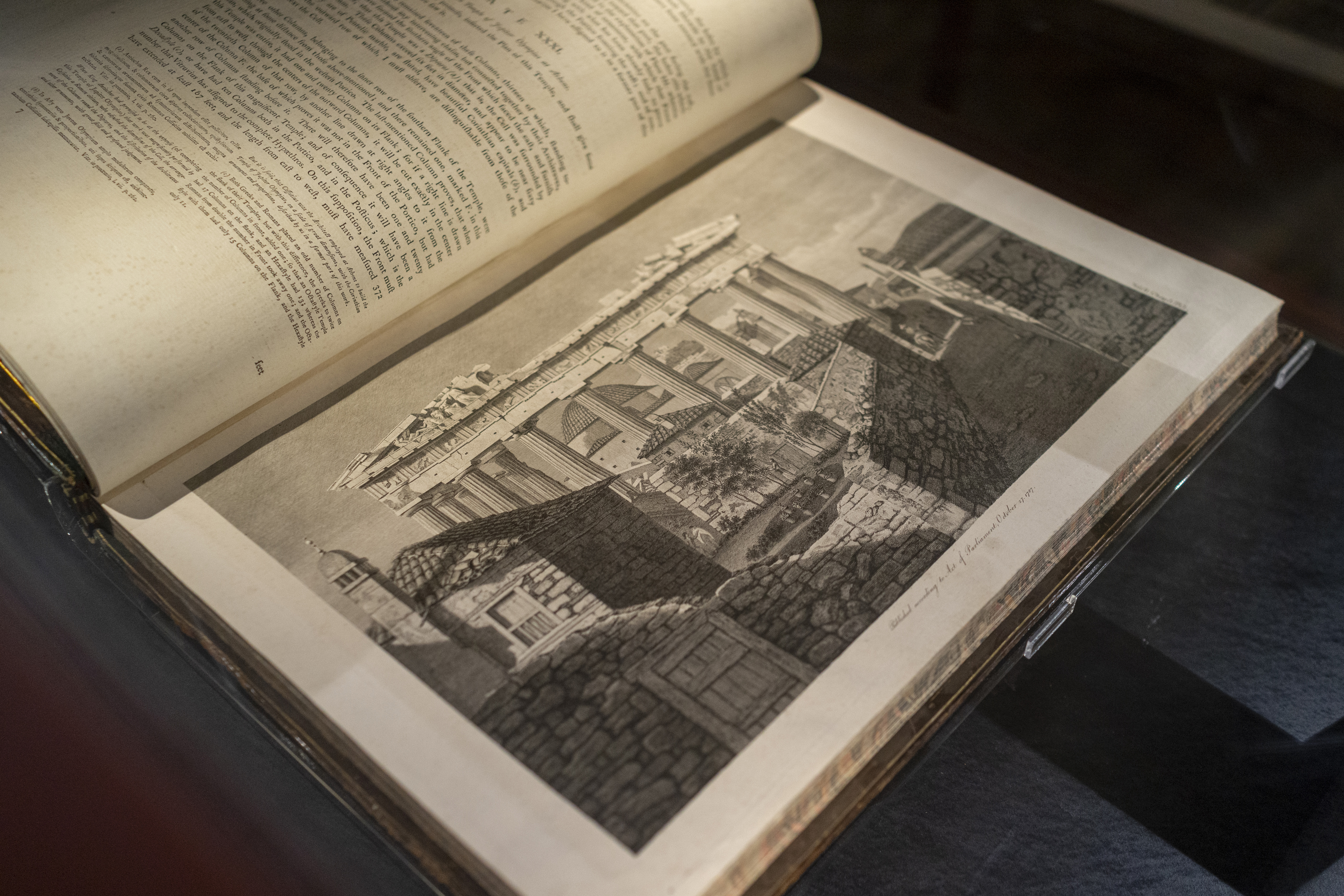

William Pars

The theatre at Miletus with the travellers crossing the river in a ferry

Pen and black ink with watercolour and gum arabic

October 1764

© Trustees of the British Museum

This drawing shows the party crossing the river Meander at Miletus. Referred to by Herodotus as the ‘jewel of Ionia’, this wealthy port city led the field in natural philosophy in the 6th century BC. The theatre of Miletus, one of the largest in Asia Minor, is seen in the middle of the image.

Richard Chandler, antiquary, epigrapher and expedition leader, stands self-assured on the ferry, with architect Nicholas Revett about to board. Behind him, chaos seems to threaten as Pars’s horse rears nervously. The travellers are accompanied by a retinue of hired local attendants including guides, translators, cooks and janizaries (bodyguards) who were crucial to the success of the expedition. They helped to navigate the Ottoman Empire, with its powerful Agas (local rulers) and terrifying bands of brigands.

Who were the travellers?

Richard Chandler (bap. 1737, d.1810): The leader of the expedition, Richard Chandler was only 27 when it departed. He was a promising scholar at Oxford, having already published a volume of fragments of Greek poets and an account of the marble collection of Oxford University, Marmora Oxoniensia (1763). This meant he was well placed to understand the ancient objects and inscriptions encountered on the expedition. Chandler went on to publish a diary account of the expedition and Inscriptiones Antiquae which detailed the ancient inscriptions the travellers encountered. He also wrote the text for Ionian Antiquities, the illustrated account of places visited. Chandler went on to have a successful academic career at Oxford.

Nicholas Revett (1721-1804): Nicholas Revett was 43 when the expedition departed. In the early 1750s he had accompanied James Stuart on an expedition to Athens and, on their return, the pair were invited to join the Society of Dilettanti and published The Antiquities of Athens. This illustrated account of the sites visited was highly influential. On the 1764 expedition, Revett made detailed measured drawings of the ruins encountered which were published in Ionian Antiquities. He remained a prominent member of the Society of Dilettanti and was the architect of a number of buildings in the Greek style.

William Pars (1742-1782): William Pars was only 22 when he was appointed to the Ionian expedition. He had just begun to exhibit paintings in oils at the Society of Arts in the Strand, London, and was teaching drawing at his brother’s academy nearby. His training had included life drawing and drawing from casts at the Royal Academy of Arts and he had also learnt to draw landscapes from nature on the spot – all useful skills for the expedition artist. It was his job to record not only the landscape and ruins, but also the sculptures they found and the local people they travelled with and encountered. The sketches he made on the spot were worked up into the finished watercolours after the travellers’ returned to England. After the expedition, he worked for patrons in England as well as in Switzerland, Ireland and Italy, where he died aged 40.

The Sponsors: The Society of Dilettanti